Building on previous critical theory approaches to an experiential paradigm of digital labour, this article considers the pervasiveness of further discursive formations of user experience (UX) apparent in workplace computational cultures.1 Closely aligned to broader ‘frictionless’ Silicon Valley ideologies,2 and an emotional turn in human computer interaction (HCI) research,3 UX has also become increasingly congruent with HR ‘change management’ and technology implementation strategies.4 Yet, notwithstanding crucial interventions from critical library studies, the pernicious role of UX-informed assumptions in the management and control of digital labour has largely avoided analytic scrutiny.5

One reason for this important oversight is that UX arguably operates behind a discursive veil of value-neutrality—that is to say, it presupposes that to create an efficient system for all stakeholders, service design should be centred primarily on satisfying user needs. However, as Maura Seale, Alison Hicks, and K. Nicholson contend, the prevailing discourse of benevolent user responsiveness highlights major epistemological gaps in UX’s scant critical self-reflection.6 In short, it is argued that UX functions according to consumerist frameworks that misleadingly claim to transfer control to the user. In effect, instead of empowering users by engaging with the complexity of their needs, this managerial ruse reduces the need itself to consumable moments of interaction, thereby silencing and excluding the broader cultural dimensions of user experience in the workplace.

By further unpacking these epistemological deficits, this article focuses on a recent convergence between conventional UX principles and ideas drawn from positive psychology and wellbeing. So-called Positive UX supplements earlier principles—including user centrality, satisfaction, friendliness, and ease of use—with more serpentine managerial strategies, including those significantly based on salutogenic approaches to work. In short, these strategies focus on improving workplace resilience through direct interventions into well-being, for example, rather than attending to pathogenic harms caused by such things as excessive workloads, toxic environments, or poor leadership. Advocates of this approach consequently assert that Positive UX leverages intrinsic motivation, eudaimonic wellbeing, and flow states to optimize worker productivity beyond basic task completion.7 Prior to highlighting key underpinning concepts drawn directly from positive psychology and wellbeing, the article traces the origins of Positive UX to Don Norman’s influential work on emotional design. The discussion subsequently follows Norman’s line of influence to conceptual frames supporting Positive UX research, as well as pertinent examples of emotional technologies used in managerial workplace strategies. In practice, it argues, the elicitation of measurable positive emotion at work often conceals deeply flawed or purposefully hidden modes of worker control. Crucially, the use of salutogenic flow states to boost worker efficiency significantly diverts attention away from addressing workplace pathologies and prejudices. Critically, therefore, I will argue that the much-coveted seamless flows of Positive UX not only diminishes a worker’s capacity to fully grasp the material conditions of labour in technological production. It also flattens difference, and silences the apathies, anxieties, stresses, overloads, depressions, and general boredom associated with digital labour.

To address further epistemological gaps arising from its salutogenic assumptions, the article conceptually reframes Positive UX on a trajectory between Foucauldian surveillance factories to a Deleuze-inflected affect theory of modulating power. Whereas on one hand of this trajectory, Foucauldian disciplinary regimes target the body of a subject – focusing on the “production of subjects whose behavior expresses internalized social norms,” on the other hand, positive psychology controls the “modulation of life itself.”8 As Antar Martínez-Guzmán and Ali Lara describe it, positive psychology is part of a regime that intervenes in a user’s flow of experience by way of a “set of technologies and devices that bring the body into affective states… supposed to provide happiness to the subject.”9 Indeed, seen through the lens of Deleuzean affect theory, Positive UX becomes endemic to wider regimes of happiness.10 Here, its role is not only to measure modulations of emotional labour but also to generate and pre-empt experiential overflows, justifying the rapid implementation of new and continuous workplace skills and challenges. These added burdens demand more input from digital workers, embedding them in feedback loops that not only require task execution but also mandate excesses of engagement, evolution, and role expansion.11 Moreover, the corporate discourses of Positive UX function to obscure the cultural and political impacts of transforming workplaces into environments where rapid prototyping can occur. The salutogenic cultivation of joyful flow states and erasure of pain points become mechanisms of control, positioning workers themselves as temporal UX prototypes, constantly probing and adapting to the uncertainties of market futures.

Epistemological Gaps in UX

Addressing the impact of UX methods on the workplace from within critical library studies, Seale et al. underscore a series of broad epistemological gaps in UX literature.12 Regarded as “the next big thing” in library work practices, the self-styled Library UX movement in the USA aims to uncritically “improve the practice of UX in libraries, and in the process, to help libraries be better, more relevant, more useful, more accessible places.”13 In addition to a raft of applied academic research and international conferences, a constant stream of unchallenged UX-focused strategies have been imposed on academic libraries. For the most part, however, Library UX has failed to interrogate its own major premise. That is to say, it has not critically reflected on its core proposal that it is the user’s experience, and not the service providers, that drives more streamlined and efficient engagement with the service. Along these lines, UX principles support a system of work that “encourage[s] the provision of holistic, cocreated service design” developed around the seemingly unassailable concept of user centrality.14 UX strategies therefore offer a taken-for-granted understanding of service design, uncritically acknowledged as beneficial to all stakeholders, including employees who are regarded as users at the centre of the systems they deliver.

It is arguably this assumptive, apolitical positioning of labour within UX’s stakeholder value-neutrality that discursively conceals a series of controlling strategies underpinning an industrial imperative toward lowering costs and increasing productivity. To begin with, UX’s foregrounding of consumerist utility over a genuinely impartial concern for wider cultural contexts of use, points to an apparatus of control that delimits and mobilizes user experiences within a neoliberal framework. In effect, UX engenders a consumer-subject determined by a moment of economic interaction with a “product, system, service or object.”15 By putting user experience at the centre of commercial interactions, users thus become “isolated and insulated from the broader environment in which [experience] takes place.”16 In terms of public services, like libraries or healthcare systems, UX consigns experience to a [marketized] “vacuum,” where users are constantly “disconnected,” and disengaged from, “affordances” provided by non-marketized “context, community, and culture.”17 For example, human resources in the workplace, including library workers, are no longer valued for their professional knowledge and communal value, but function merely as support for frictionless consumable products and services designed for immediate gratification.

Secondly, UX’s encapsulation of user experience within this transactional commercial framework obscures the service workers’ ontological connection to their work environment in a number of ways. Mainly, the centrality of user experience means that a worker becomes coupled to a system that “flattens the human condition.18 Interactions with other workers, and their environment, are therefore shut off or organized around “naturalized” modes of consumerism.19 As a result, by reducing interactions to a functional, objectified space of consumption, working life becomes more readily aligned to UX principles, helping to reinforce quality assurance metrics and other accountability mechanisms which generally serve the logics of economic efficiency and corporate value creation.

Thirdly, UX’s drive toward seamless design consistency constrains and oversimplifies the complex and fluid identities that conventionally inhabit workplaces. As follows, UX becomes an enactment of a kind of violence, which compresses difference in the workplace, reducing the complexities of experience to rudimentary archetypes. In the case of library work, insisting on consistency in service design risks collapsing the professional roles of librarians and scholars into frictionless interchangeable points of transactional value. One significant, yet indirect, outcome of this elimination of friction is a parallel purging of unwanted “messiness” in everyday interactions at work that are considered irrelevant to the UX system.20 Seale et al argue that this erasure of complexity leads to the exclusion of other “bodies and labor,” rendering the diversity of library experiences “hyper(in)visible.”21

It is important to add that these exclusionary practices are embedded in money-saving rationales that often justify IT initiatives and UX methodologies alike. By deploying user personas, for example, sometimes referred to as conceptual stand-ins, the diverse needs of a user group can disappear in the UX process.22 This is because in order to save a lean design team research time and money, UX personas generally provide only a shorthand description of a complex situation. Furthermore, they are often developed “without reference to user research,” and have been subsequently criticized for being little more than a “designer’s imaginary friend.”23 At best, personas offer a gross simplification of a user group, and at worst, they are a design shortcut to an imagined archetypical consumer of services; that is to say, a pseudo user group of “people who do not, ultimately, exist.”24 To be sure, as personas become increasing automated by AI, like most other data-defined persons, the UX persona is not really a person at all.25 Another UX methodology commonly used in the workplace is the experience journey map designed to trace and remove various pain-points from the service user’s interactions. By asserting the authority to explain, ease, and erase pain from a service user’s journey, UX strategies claim to be bearers of unassailable objective knowledge. It is this uncritical acceptance of objectivity that primarily silences more nuanced, intersectional, and often-conflictual community-based knowledge of library labour, and other stakeholders. Replacing it with prevailing expressions of technocratic expertise.

Fourthly, then, UX becomes a preemptive containment of multiplicity, generally conforming difference to heteronormative, white, and able-bodied categories of user. In much the same way as Ruha Benjamin contends that human-centred design thinking uncritically encodes inequity and discrimination into its methods,26 UX often imposes predetermined, step-by-step design processes and principles on everyday needs. It is vital to therefore question which users are prioritized or excluded from the implementation of UX processes and principles.27

Ultimately, Seale et al’s study follows a trajectory that connects these unchallenged UX principles to the emergence of Positive UX. Their study notes how, as such, UX discourse frequently asserts that it is “user affect and sensation” that differentiates its approach from apparent limitations of previous user-centred conceptual frameworks.28 In other words, user joy, and other emotional and nonutilitarian aspects of use set UX apart from traditional HCI and ergonomics, which focus solely on functional usage linked to cognitive and behavioural interactions. By aligning UX with an industrial obsession with induced positive affect and emotional flow states, joy has become a sought-after metric of user experience. This “concept” of joy is now positioned as crucial to best practices in the design of productive workplaces.29

UX Joy and Norman’s Positive Emotional Design

On their influential consultancy website and resource for UX guidance and training, the Norman Nielsen Group (NN/g) describe how, in order to meet the requirements for “exemplary” UX, a product or service must fundamentally address the “exact needs of the customer, without fuss or bother.”30 UX Design gurus, Don Norman and Jacob Nielsen’s approach to user experience not only encompasses the “simplicity and elegance” of good practices in conventional user interface design.31 It also aims toward producing something they refer to as the “total experience.”32 Optimal UX strategies should therefore exceed “giving customers what they say they want” or merely ticking off “checklist features” relating to functionality.33 Instead, total UX demands interdisciplinary collaboration and must deliver products that are a “joy to own, a joy to use.”34

The origins of this influential design philosophy founded on joyful experiences interestingly follows the trajectory of Norman’s career. Before pioneering the first UX architecture role at Apple in 1993, and co-founding NN/g with Nielsen in the late 1990s, he studied electrical engineering, computer science, and cognitive psychology at university.35 Indeed, prior to his interest in user joy, Norman’s contribution follows a familiar shift from early ergonomic concepts of usage, established in newly computerized engineering workshops, to wider applications of cognitive science in the design of “everyday” consumable products.36

There are several factors that connect these early phases of Norman’s influential career to current uncontested assumptions underpinning UX principles. To begin with, by contending that “nobody is ever against usability” Norman alludes to the principle of UX stakeholder neutrality.37 The potential benefits of impartially designing a system around the positive experiences of the user of a service are assumed to be incontrovertible. Norman also helps to further define the ubiquitous characteristics of total UX, contending that it was always supposed to be a concept that included “everything” about the experience with the product or service. “It’s the way you experience the world,” Norman argues. “It’s the way you experience your life… it’s a system that’s everything.”38 Formidably framed by a discourse saturated with affirmative adjectives, like satisfying, easy, pleasing, and friendly, NN/g’s UX is all about the enhancement and improvement of a person’s overall experience. Significantly, messier encounters, which might prove to be frustrating, confusing, overloading, tedious, or even painful, are supposedly erased from the user experience journey.

Notably, in 2004, Norman published a new influential design thesis called Emotional Design: Why We Love (or Hate) Everyday Things. This text is crucial to understanding the onset of Positive UX for two related reasons. Firstly, informed by a rudimentary engagement with neuroscientific studies of emotion, Emotional Design emphasizes the role of positive emotions in user experience. Secondly, Norman’s book is implicitly linked to the guiding principle of positive psychology. It argues, as such, that attractive designs do not merely add pleasing aesthetic value to a design. They evoke joy and delight, which makes users more relaxed, creative, and open to problem-solving. Consequently, the link between joyful emotional experiences, enhanced functional usage, and productivity, becomes integral to UX strategies

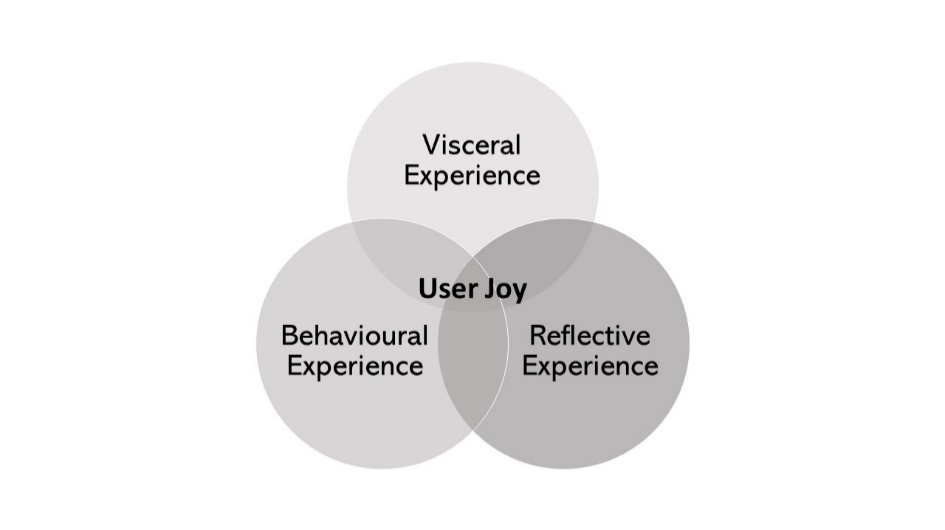

From the early 2000s, a flourishing UX industry of designers, consultants, and marketers begin to draw inspiration from a more general emotional turn. This focus on predominantly positive emotions, originating from the popular neuroscience interpretation of the emotional brain thesis and overlapping with positive psychology, has become as significant as cognitive and behavioural factors in design, marketing, branding, and customer experience strategies.39 Particularly illustrative to these developments in the experiential industry is Norman’s ubiquitous Venn diagram showing three overlapping levels of experience processing (see figure 1). The first level emphasizes conventional elements of usability, focusing on user behaviours related to functionality and performance. The second level addresses cognitive interactions, involving higher-level reflective assessments of experience, filtered through conscious personal meaning-making, values, and memories. It is, nonetheless, Norman’s third visceral level, experienced through nonconscious, immediate sensory impressions, which again links UX principles to concepts developed in positive psychology. As follows, the visceral level is supposed to create positive flow-like states where users supposedly become non-consciously immersed in seamless and engaging interactions. Moreover, comparable to the prioritization of positive emotions as a pathway to eudaimonic wellbeing in positive psychology, all three of Norman’s levels of experience converge in the concept of user joy or delight.

The relation established between positive psychology and the development of UX becomes more explicit when Marc Hassenzahl, Michael Burmester, and Franz Koller publish their Positive UX manifesto, User Experience Is All There Is.40 In this text, the authors cite Emotional Design as a distinctive “180-degree turn” from conventional “cognitive engineering perspective[s]” to a new design paradigm in which usability isn’t everything!41 Norman’s work therefore marks a moment when UX researchers realize that there is “more to the quality of interactive technology than mere effectiveness and efficiency.”42 Indeed, designers need to embrace the importance of “hedonic, beauty, emotions, [and] joy.”43 The intention of Positive UX is to consequently go beyond functional design, and serviceability, by embracing the hitherto untapped “emotional value, and the “Wow” of technology.”44

It is significant to also note how the conceptual development of Positive UX is clearly aligned to industry needs. As follows in the manifesto, even before he read Norman’s book, it would seem, the strategic link between applied UX research and the requirements of the technology sector became self-evident to Hassenzahl. After attending an inspirational industry keynote back in 1997 by the then Director of Strategic Technology at Sun Microsystems, Bob Glass, he realized that old methods were failing to keep pace with dynamic industry trends associated with the emotional turn. It is apparently at this earlier point that Hassenzahl initially recognized that a “new metrics and techniques to measure joy of use will need to be developed.”45

Conceptual Development of Positive UX

The conceptual development of positive user experience in the workplace has been contrasted to principles underpinning Fordist management of labour productivity.46 Unlike the top-down managerial control of repetitive physical tasks that prioritize efficiency over worker autonomy and creative labour, Positive UX aims to enhance individual performance and productivity by supporting “individual innovativeness, inspiration, and creativity.”47 The core principles behind this reconfigured mode of digital labour can be traced back to the influence of positive psychology’s salutogenic approach on a wide range of phenomena.48 As a supposed antidote to mainstream psychology’s focus on negative pathogenic causes and consequences, salutogenesis distinctively draws on a positivist framework to prioritize positive human development. Positive UX builds on evolved salutogenic principles to argue that if positive affect can boost task performance, even in the presence of negative factors, its deliberate cultivation will further boost worker productivity.

To understand how salutogenesis has shaped Positive UX, we need to acknowledge its extended use of a series of associated positive psychology concepts more generally. These include intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, induced positive affect and cognition, hedonic and eudaimonic experiences, and flow state. For example, Positive UX researchers have drawn on intrinsic motivation concepts adopted in computer games design.49 “Wouldn’t it be desirable,” Harbich and Hassenzahl propose “to work in an environment where the design of technology is as “motivating… and enjoyable” as playing a computer game.50 Evidently, there are stark contrasts to be made between “work and entertainment” and “tools” and “toys,” they concede.51 Not least because workers and gamers are subject to entirely different modes of user choice and control. However, “work does not differ much from play,” they contend, in the sense that “goal-directed behaviour” is supported by varying motivational experiences with technology.52 On one hand, workers are extrinsically rewarded for completing a given task. They might, for instance, put up with using badly designed tools, not because they enjoy them, but to get the job done and earn money without necessarily needing to become emotionally attached to a task. Gamers are, on the other hand, supposed to be intrinsically motivated by the activity itself, for its own sake, or the sheer joy of doing it. Gamers tend to seek out novelty and challenges, to extend and exercise their capacities, to explore, and to learn – all of which, Harbich and Hassenzahl significantly contend, “leads to well-being.”53 Intrinsic motivation also appears to induce positive affect, which can, despite negative usability issues, result in “perceived enjoyment…” and significantly “lead to more usage.”54 Moreover, by explicitly equating user joy with the positive psychology concept of “flow,” Hassenzahl links the experience of being “high on stimulation” to situations that allow for challenges to be overcome.55

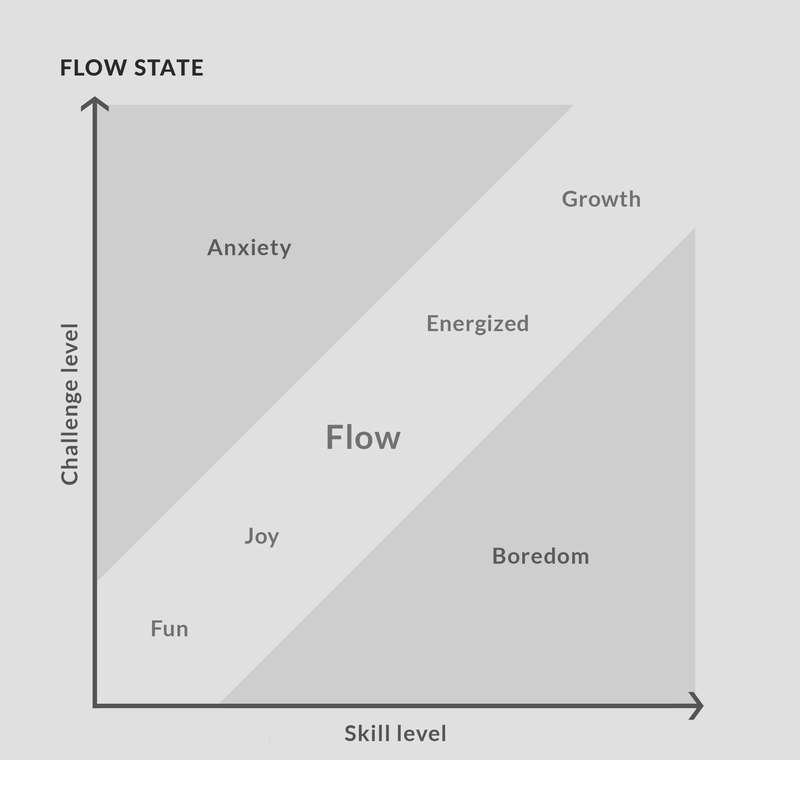

To further understand how the salutogenic principles of positive psychology and wellbeing underpin the logic of Positive UX, it is useful to unpack Harbich and Hassenzahl’s workplace model. In effect, their step-by-step (execute, engage, evolve, and expand) UX process draws on the joyful experience of intrinsic motivation to drive productivity. Firstly, they assert that the work process must achieve the execution of a task. After all, workers always have “work to do.”56 Secondly, however, rather than using technology as a means to an end – to get the job done, Positive UX aims to stimulate “playful” user engagement.57 This is supposed to boost productivity by inducing positive affect and encouraging workers to further explore workplace tasks. The third step is consequently intended to support a continual evolvement of worker potential through reorganizing and adapting to work tasks. Ultimately, by harnessing stimulations associated with gameplay, Positive UX purports to make flow thrive in the workplace. Which is to say, following NN/g’s key definition of flow, users experience “an enjoyable mental state of extreme focus provided by the perfect balance of challenge and skill.”58 Joyful play thus creates a flow channel between the tedium and anxieties often associated with task completion (see figure 2). Crucially, then, the final step of the model looks to expand on the intrinsic advantages of interacting with work tools “in a playful way.”59 By seeking out “new and better ways of getting things done,” workers can even “surprise and astonish boss[es] and colleagues” alike, as they execute “additional tasks” beyond those in their initial remit.60

Metrics, Moods, and Other Pulses

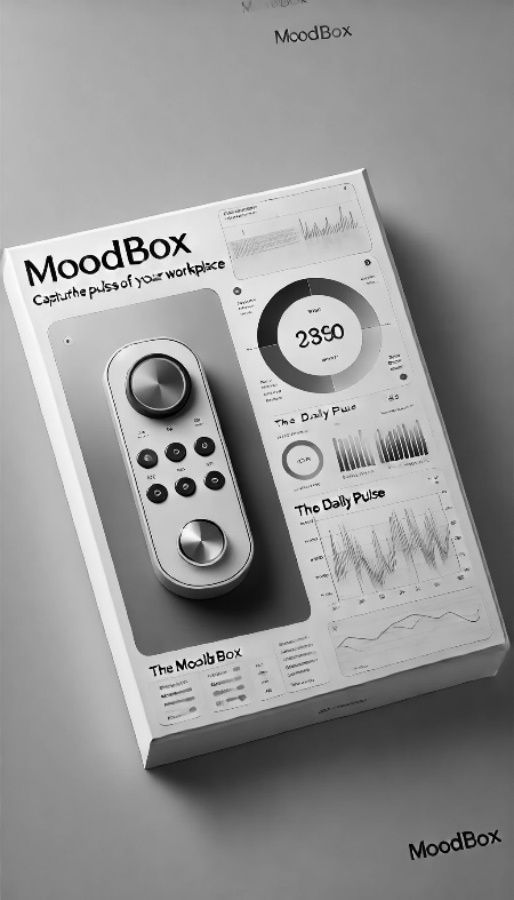

Despite Positive UX’s ambition to present industry with a reliable measure of joy, it is significant to stress that most of its innovations are currently limited to either conceptual or prototype stages of development. In practice, the design and implementation of emotional technologies in the workplace has proven to be more problematic in terms of offering a consistent metric. Will Davies’s account of Moodbox, for example, points to the flawed emotional design of a technology intended to monitor the modulating pulses of positive and negative moods in the workplace.61 Using a simple interface with red and green buttons, Moodbox was designed for employees to log their mood at the end of the working day.62 In effect, they would select green for positive or red for negative. The collected responses were then visually aggregated and sent to a central database. The resulting data, known as The Daily Pulse, was then graphically displayed on a dashboard, theoretically allowing managers to monitor employee mood changes over time (see figure 3).

Davies’s critical analysis of Moodbox begins by raising questions concerning the promise of emotional consensus theoretically built into the design of its voting system. He notes how the designers “deliberately avoided a neutral option, thereby requiring a choice to be made one way or the other.”63 However, by requiring votes to be cast in this way, it becomes impossible to prevent a lone employee from repeatedly pressing a button. This significant flaw in the device highlights possible deceptions and a failure to represent workplace moods authentically, or indeed, democratically. Yet, when quizzed by Davies about the problem, the developers didn’t see it as a system defect. “Yes, people could cheat,” they said, but…

… nonetheless, maybe the fact of things is that there have been so many pulses, that is factual… the key thing is that metric is useful for you to improve.64

In contrast to conventional pulse surveys, which aim to provide managers with a general measures of employee engagement, morale, and levels of workplace stress, Moodbox’s metric singles out individual performances. For instance, if a worker repeatedly presses the red button while most colleagues press green, the device might single out the unhappy worker as “part of the problem.”65 Along these lines, the developers contend that Moodbox may trigger a period of self-reflection, but an “unhappy employee might also, over time, come to appear like they’re ‘out of step’… with the rest of the company.”66 Significantly, the technology differs from conventional appraisals of worker performances, judged, and decided on, periodically by managers according to general criterion. Instead, this platform presents continuous feedback on individual emotional experiences at work, which can emerge to be automatically assessed.

More recent work-based emotional technologies draw on an evolved series of wellbeing concepts similar to Positive UX. The Virgin Pulse app, for example, provides a “suite of workplace wellbeing products and services, which together promise ‘technology to replenish the modern worker.’”67 Crucially though, this app pushes the responsibility for the maintenance of positive work experiences onto the employee. As their marketing documentation makes clear, Virgin Pulse requires the worker to monitor (and reward) their own behavioural patterns relating to workplace enjoyment and stress, as well as sleep routines, and other activities that impact on “healthier and happier” lifestyles.68 Markedly like Moodbox, Virgin Pulse is “integrated with other HR systems, and produces a wellbeing data dashboard for managers to inspect.”69 Yet, the app functions uniquely insofar as it requires the worker to take responsibility for partially managing their own modulating pulses of health and happiness.

Davies’s interest in wellbeing technology notably occurred before the dramatic rise in remote work practices following the COVID-19 pandemic. In this respect it is salient to point out that the post-pandemic marketing proposition for Virgin Pulse has subsequently altered. The apparent threat of largescale workplace optouts in certain sectors, has seemingly intensified an already fragile political economy struggling to manage costly modulations of negative workplace emotion. Virgin Pulse therefore offers overstretched HR managers a cost-cutting solution. Updates have been informed by a contested backdrop of what the app’s marketing team call an “increasingly volatile labour market driven by so-called the Great Resignation, quiet quitting and a multitude of growing health problems such as burnout and anxiety.” 70 The app has hence been strategically repositioned as a wellbeing platform with analytics that can substantially reduce HR admin loads.71

There appears to be a growing market trend toward cost-cutting HR wellbeing technologies, inevitably including emotional AI solutions. Aligned with Davies’s analysis, other authors have been critical of claims that these new emotional technologies simply aid managers in making the post-COVID workplace a happier and more satisfying environment. Peter Mantello and Manh-Tung Ho point to the costly volatility of labour markets of discontent and large-scale absenteeism, mostly driven by negative emotions relating to the fear of “precarity… insecurity, economic instability.”72 Consequently, many employers have apparently welcomed emotion-tracking devices and data-driven wellness programs since they might allow managers to leverage greater control over a volatile labour force working in the new normal of mostly unregulated hybrid and remote workplaces.73

Regimes of Happiness

Thus far, this article has argued that flawed Positive UX design principles reinforce discursive control and functional mechanisms in the digital workplace. In this respect, salutogenic approaches align with a broader trajectory of power relations, spanning Foucauldian disciplinary societies and Deleuzean control societies. On one hand, the emphasis on producing observable positive emotions and wellbeing in the workplace can be mapped to an earlier analysis of positive psychology.74 By way of privileging, classifying, and categorizing particular modes of positive “character strengths and virtues,” for example, salutogenesis frames its approach to subjectivity within the limits of a neoliberal entrepreneurial domain of capitalism.75 Positive UX can therefore play a part in optimizing efficiency, docility, and predictability of labour, while also dividing a “subject from her world,” and reducing “her powers and potentialities” to act in it.76 On the other hand, though, the measuring, modifying, and mobilizing of emotional employee experience, exhibits some distinct post-panoptic Deleuzean functions. These new regimes of happiness help to ensure that workers are both compliant with “the mood of the organisation,”77 and consequently more productive. The overall goal is to attempt to introduce more predictable flows of worker positivity into an unpredictable political economy, destabilized by oscillations between worker anxiety, boredom, and other mental and physical health problems.

Expanding on Martínez-Guzmán and Lara’s Deleuzean framing of the “epistemological and ontological problems” of embedding positive psychology into self-help apps, it is possible to see how fitness for work is no longer solely determined by “institutional psychological authorities.”78 The maintenance of a flourishing career requires that workers become detached from institutional power mechanisms exemplified in the surveillance factory and connect instead to happiness technologies, which “reconfigure and move beyond… [these Foucauldian] objects and power strategies.”79 Along these lines, these new regimes produce technologically enhanced, self-regulating subjects, seemingly measuring and optimizing their own positive psychological flow states.

Before exploring further developments in workplace control, we can thus far sum up Positive UX’s role in these regimes in terms of generating alternatives to the surveillance factory model. Unlike conventional methods of efficiency control that rely on observing and measuring task completion, Positive UX connects workplace productivity to biological alignments and health indicators. Although attaining happiness is often associated with beneficial health outcomes, in this context, “emotional and more pleasure-oriented” experiences are also concretely linked to driving economic value through increased productivity.80 The regime’s objective pivots around the inducement of positive affect, so that joyful flow states in the workplace can be productively optimized to exceed their limits. The objective is to therefore manage thriving positive flows, steer them away from the negative impulses of boredom and depression, and ensure that workers go beyond the mere execution of tasks by engaging, evolving, and expanding on their given role.

Crucially, however, the often-overstated potential of these Positive UX solutions in the workplace reveals more epistemological gaps. Applied researchers have largely failed to critically examine the negative implications of using positive psychology and wellbeing at work. In effect, they omit to consider how “mind and body can be assessed as economic resources, with varying levels of health and productivity.”81 Moreover, despite its promise to push the inhibitors of boredom and anxiety to the margins of work experience, Positive UX’s salutogenic approach actively disregards the wider consequences of persistently harmful physical, emotional, and psychological pathologies. Worse still, this framework encourages the use of self-help technologies to manage wellbeing and flow states, effectively shifting accountability for workplace pathologies from employers to employees. Perpetuating this cycle, the turn to happiness—occurring against a backdrop of cuts to workplace support structures—appears to enable managers to strategically avoid costly issues like workplace fatigue and depression, instead prioritizing competitive ‘hedonic’ advantages.82 Some management and leadership experts even argue that “there may be no other way to” remain competitive in the workplace than by boosting one’s own flow state to amplify “performance and productivity.”83 This entails continually working in a personalized “flow channel” between boredom and anxiety—“the spot where the task is hard enough to make us stretch; not hard enough to make us snap.”84

More critical attention needs to be directed towards the implication of compelling workers to function in temporal flow channels described by Positive UX.

Experiential Overflows and the Temporality of UX

In a research context, Positive UX appears at the vanguard of a transition from conventional ergonomic and cognitive observations of technology usage (usability) to novel interventions into experiences of use (UX). On one hand, established usability methods utilize tools from HCI research to observe and evaluate physical and mental interactions. Usability studies typically capture evidence for the redesign of workplaces by observing employee behaviour and choice-based activities.85 On the other hand, novel UX methodologies, such as experience journey maps, aim to move beyond behavioural and cognitive interactions. These maps trace the modulating “peaks and valleys” of experiential curves, prioritizing hedonic “pleasurability” over negative experiences in the workplace.86 They plot existing experiences, identifying, erasing, and replacing associated pain-points with added positive “experiential value,”87 while also creating long-term “opportunities for making [new] experiences” happen based on further hedonic interventions.88

We can refer to these new opportunities as experiential overflows since they not only correspond to preexisting categorizations of workplace experiences.89 These overflows present occasions for workplace researchers, designers, and practitioners to produce measurable excesses of experience. The objective is to generate enough workplace action so that frequent testable variables can be experimented on.90 Positive UX tools subsequently enable the clustering of workplace experiences in the flow channel between the vertical and horizontal axes of new challenges and skills acquisition. To put this another way, Positive UX cultivates experiences complementary to the managerial goal of making future flow thrive.

In terms of asserting power relations at work, the projected nature of these overflows of experience seems to exceed the observations of work in the spatial enclosures of factory labour. What escapes observation is nevertheless recaptured by a temporal regime that increasingly governs worker subjectivation. There are analytical prerequisites concerning this kind of temporal power relation at work. E.P. Thompson’s contrast between the seasonal rhythms of pre-industrial labour and the internalizing of industrial time-discipline, and Paul Viriolo’s “speed factories,” wherein acceleration and immediacy begin to dominate every aspect of human experience, for example.91 In short, the excesses of workplace experience no longer need to be confined to observational spaces—in order to thrive, work itself must now flow! This is not to say that flows of experience are simply managed by way of constant time-based tasks. Rather, UX is all about keeping step with the future. Its strategies are intended to “go far beyond user needs and wants,” and churn out predictive insights into potential usage with future market potential.92

This is the UX rationale behind doing rapid iterative prototyping. This method is similarly designed to escape the spatial enclosures of the factory model by embedding users in the temporality of successive feedback systems that help to predict patterns and provide insights into what might happen over time. To combat Schumpeter’s Nietzsche-inspired waves of creative/destruction, and their Silicon Valley offspring of digital disruption, 93 UX prototypes become integral to an industrial sector infused with an “innovation fetish.”94 UX thus “becomes entwined with attempts to read the future, to create value, and to make strategic decisions and generate profits.”95 Beyond the discourse of stakeholder value-neutrality, the temporality of Positive UX becomes a “political necessity” intended to produce entrepreneurial stability in the instabilities of market flux.96 Its aim is to…

… ensure that corporations feel secure in their existing identity, products, and services, thereby justifying their own stasis.97

To understand how these endeavours to read the future significantly align with an affect theory interpretation of the Deleuzean control society thesis alluded to earlier, it is useful to again expand on Martínez-Guzmán and Lara’s critical intervention. This is because their work usefully traces how the concept of preemption operates within neoliberal expressions of positive psychology. To be sure, they draw on affect theory to suggest that neoliberal subjectivation is derived from a preemptive power that influences and controls the unpredictability of modulating affective labour.98 As Patricia Clough puts it, the political present is “set in relation to a preemptive modulation of futurity.”99 This is a power dynamic that “aims at the not-yet actualized… to find a resource for energy in the virtuality” of an implicated order of things, yet to come.100 Like positive psychology’s regime of preemptive salutogenesis, then, UX’s inducements of positive affect strive to make future experiences “tangible in the present.”101 In other words, by way of centring the user as a prototype in an iterative design process, UX creates conditions that might avoid future risks and protect investments made in the present.

Before concluding, it is important not to lose sight of the flawed nature of Positive UX solutions like those discussed in Library UX literature. Despite the advantages of generating multiple versions to test expectations, anticipate the future, and reduce the risk of costly redesigns, prototypes can also introduce significant instabilities. Contrary to professional Library UX discourses, which pressure workers to uphold the principle of user-centrality or “risk their future survival,” there is a strong focus on rapid, cost-effective experimentation. Relying on low-fidelity prototyping cycles and guerrilla-type “DIY solutions for the busy librarian” complicates any attempt to anticipate the future.102 Crude, stopgap methods often fail to provide accurate predictions or meaningful insights. They can result in unworkable or impractical solutions. The vague, contradictory, or even imaginary versions of user experience conceal the “cash-strapped” reality for most libraries, looking for a quick, low cost fix.103 Library UX may provide a cost-effective way of rearranging the workplace, but the “superficiality of [its] methods” diminish the concept of experience used to understand user interaction.104 Indeed, some cynical UX librarians admit that although their presence in the workplace may make the library seem more “hip and moving forward in a faster way than may be true,” their actual role is a fictitious performative exercise.105

Some Conclusions

The temporality of Positive UX provides a trace of novel modes of control that potentially escape the normalizing enclosures of the Fordist factory . These overflows of experience certainly do not resemble the regimented temporalities of assembly line labour and consequently exceed discursive formations of unaffected docile worker bodies. Instead, they aim to capture, and put to work, the flow states of positive affect, feeling, and emotional experiences in the workplace. Nevertheless, this idealized implementation of Positive UX as a value-neutral driver of productivity needs to be seen alongside the increasing requirement for speedy and repetitive labour in computational workplaces where tasks—more often than not—tend to overflow. Pressurized workers are expected to swiftly transition from one task to another, without necessarily completing the previous one. Contrary to the centrality of user experience, it seems, the introduction of hastily implemented, often-botched, DIY solutions to the problem of task overflow ensures that responsibility is continually pushed away from the centres of organizational power—and its middle managers. Obligation, accountability, and duty, all move toward a peripheral end-user. Indeed, this is the almost obscured UX principle of user responsibility—related to the Silicon Valley concept of responsibilization, which describes a process whereby: “subjects are rendered individually responsible for a task which previously would have been the duty of another.”106

User responsibility for managing an endless overflow of tasks is perhaps the clearest indication that workplace experiences have moved from disciplinary spaces of the factory toward the temporal modulations of control societies. Certainly, in disciplinary societies, as Gilles Deleuze contends, “one was always starting again (from school to the barracks, from the barracks to the factory).”107 In the societies of control however, “one is never finished with anything.”108 In conclusion, then, the positive overflow of new challenges and skills just keeps on coming. Work is intended to be intrinsically satisfying. Nonetheless, there is no space for a temporal break from the flux of frustratingly incomplete tasks, remote managerial control, perpetual user experience feedback, or acceptable extrinsic rewards. The rapid, iterative, yet makeshift prototyping of the worker (and their tools) seems to ensure that while they are constantly expected to expand on their roles, and apparently enjoy doing so, workers are always required to manage their own work-related health risks, fix things when they go wrong, and of course, try to impress the boss by continually doing extra stuff! To fight these flows—to struggle for the experience of work—creative living labour must find new weapons—it needs new experiments with experience.109

Bibliography

Baker, Stephanie Alice. “From the Wellness Movement to the Wellness Industry.” In Wellness Culture, 41–73. Emerald Group Publishing Limited, 2022.

Babapour, Maral, and Antonio Cobaleda Cordero. “Contextual User Research Methods for Eliciting User Experience Insights in Workplace Studies.” In Future Workspaces, 265–75. 2020.

Benjamin, Ruha. Race after Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code. John Wiley & Sons, 2019.

Chafi, Maral Babapour, and Antonio Cobaleda Cordero. “Contextual User Research Methods for Eliciting User Experience Insights in Workplace Studies.” Future Workspaces (2020): 265–75.

Clough, Patricia Ticineto, Greg Goldberg, Rachel Schiff, Aaron Weeks, and Craig Willse. “Notes towards a Theory of Affect-Itself.” Ephemera: Theory and Politics in Organization 7, no. 1 (2007): 60–77.

Davies, Will. “The Political Economy of Pulse: Techno-Somatic Rhythm and Real-Time Data.” Ephemera 19, no. 3 (2019): 513–36.

Gidali, Sagi. “Office Design Matters More Than Ever: Using UX Principles Can Help.” Forbes, February 15, 2023. https://www.forbes.com/sites/allbusiness/2023/02/15/office-design-matters-more-than-ever-using-ux-principles-can-help/.

Gray, Colin M., Yubo Kou, Bryan Battles, Joseph Hoggatt, and Austin L. Toombs. “The Dark (Patterns) Side of UX Design.” In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–14. 2018.

Harbich, Stefanie, and Marc Hassenzahl. “Beyond Task Completion in the Workplace: Execute, Engage, Evolve, Expand.” In Affect and Emotion in Human-Computer Interaction: From Theory to Applications, edited by Christian Peter and Russell Beale, 154–62. Vol. 4868. Springer Science & Business Media, 2008.

Harrison, Steve, Deborah Tatar, and Phoebe Sengers. “The Three Paradigms of HCI.” In Alt. Chi. Session at the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, San Jose, California, USA, 1–18. 2007.

Hassenzahl, Marc. “Emotions Can Be Quite Ephemeral; We Cannot Design Them.” Interactions 11, no. 5 (2004): 46–48.

Hassenzahl, Marc, Michael Burmester, and Franz Koller. “User Experience Is All There Is: Twenty Years of Designing Positive Experiences and Meaningful Technology.” i-com 20, no. 3 (2021): 197–213.

Hornbæk, Kasper, and Morten Hertzum. “Technology Acceptance and User Experience: A Review of the Experiential Component in HCI.” ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction (TOCHI) 24, no. 5 (2017): 1–30.

Kemper, Jakko. Frictionlessness: The Silicon Valley Philosophy of Seamless Technology and the Aesthetic Value of Imperfection. Bloomsbury Publishing USA, 2023.

Kolodziejski, Steven. “Create a Work Environment That Fosters Flow.” Harvard Business Review, May 6, 2014. https://hbr.org/2014/05/create-a-work-environment-that-fosters-flow.

Mantello, Peter, and Manh-Tung Ho. “Emotional AI and the Future of Wellbeing in the Post-Pandemic Workplace.” AI & Society (2023): 1–7.

Martínez-Guzmán, Antar, and Ali Lara. “Affective Modulation in Positive Psychology’s Regime of Happiness.” Theory & Psychology 29, no. 3 (2019): 336–57.

McDonald, Matthew, and Jean O’Callaghan. “Positive Psychology: A Foucauldian Critique.” The Humanistic Psychologist 36, no. 2 (2008): 127–42.

Mlekus, Lisa, Dominik Bentler, Agnieszka Paruzel, Anna-Lena Kato-Beiderwieden, and Günter W. Maier. “How to Raise Technology Acceptance: User Experience Characteristics as Technology-Inherent Determinants.” Gruppe. Interaktion. Organisation. Zeitschrift für Angewandte Organisationspsychologie (GIO) 51, no. 3 (2020): 273–83.

Norman, Don. The Design of Everyday Things. Basic Books, 1988.

Norman, Don. Emotional Design: Why We Love (or Hate) Everyday Things. Basic Books, 2007.

Norman, Don, and Jakob Nielsen. “Definition of User Experience (UX).” Nielsen Norman Group. Last modified August 8, 1998. Updated December 19, 2022. https://www.nngroup.com/articles/definition-user-experience/.

Norman, Don. “Don Norman: The Term ‘UX.'” YouTube video, 2:45. Posted August 8, 2017. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9BdtGjoIN4E.

Rasila, Heidi Marja, Peggie Rothe, and Suvi Nenonen. “Workplace Experience–A Journey Through a Business Park.” Facilities 27, no. 13/14 (2009): 486–96.

Reinert, Hugo, and Erik S. Reinert. “Creative Destruction in Economics: Nietzsche, Sombart, Schumpeter.” In Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900) Economy and Society, 55–85. 2006.

Sampson, Tony D. A Sleepwalker’s Guide to Social Media. John Wiley & Sons, 2020.

Sampson, Tony D. The Assemblage Brain: Sense Making in Neuroculture. University of Minnesota Press, 2016.

Seale, Maura, Alison Hicks, and K. Nicholson. “Towards a Critical Turn in Library UX.” FIMS Publications 83, no. 1 (2022).

Seligman, Martin E. P., and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. “Positive Psychology: An Introduction.” American Psychologist 55, no. 1 (2000): 5–14.

Sponheim, Caleb. Encouraging Flow State in Products. Nielsen Norman Group. YouTube video, 3:29. Posted April 13, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c97hSXahVNI.

Virgin Pulse. “Reduce Your HR Admin.” Accessed April 16, 2024. https://community.virginpulse.com/en-gb/reduce-your-hr-admin.

Weave: Journal of Library User Experience. Accessed April 15, 2024. https://journals.publishing.umich.edu/weaveux/.

Zeiner, K., Burmester, M., Haasler, K., Henschel, J., Laib, M., & Schippert, K. “Designing for Positive User Experience in Work Contexts: Experience Categories and Their Applications.” Human Technology 14, no. 2 (2018): 140–75. https://doi.org/10.17011/ht/urn.201808103815.

Notes

- Steve Harrison, Deborah Tatar, and Phoebe Sengers, “The Three Paradigms of HCI,” in Alt. Chi. Session at the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (San Jose, California, USA, 2007), 1–18. T.D. Sampson, The Assemblage Brain: Sense Making in Neuroculture (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016). ↩

- See for example and articulation of Silicon Valley ideology in Jakko Kemper, Frictionlessness: The Silicon Valley Philosophy of Seamless Technology and the Aesthetic Value of Imperfection (New York: Bloomsbury Publishing USA, 2023). ↩

- See work on emotion, UX, and the experience economy in T.D. Sampson, A Sleepwalker’s Guide to Social Media (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2020). ↩

- Kasper Hornbæk and Morten Hertzum, “Technology Acceptance and User Experience: A Review of the Experiential Component in HCI,” ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction (TOCHI) 24, no. 5 (2017): 1–30; Lisa Mlekus et al., “How to Raise Technology Acceptance: User Experience Characteristics as Technology-Inherent Determinants,” Gruppe. Interaktion. Organisation. Zeitschrift für Angewandte Organisationspsychologie (GIO) 51, no. 3 (2020): 273–283. ↩

- Maura Seale, Alison Hicks, and K. Nicholson, “Towards a Critical Turn in Library UX,” FIMS Publications 83, no. 1 (2022). ↩

- Ibid., p. 6. ↩

- Stefanie Harbich and Marc Hassenzahl, “Beyond Task Completion in the Workplace: Execute, Engage, Evolve, Expand,” in Affect and Emotion in Human-Computer Interaction: From Theory to Applications, ed. Christian Peter and Russell Beale (Berlin: Springer, 2008), 154–162. ↩

- Antar Martínez-Guzmán and Ali Lara, “Affective Modulation in Positive Psychology’s Regime of Happiness,” Theory & Psychology 29, no. 3 (2019): 336–357, at 341. ↩

- Ibid., 340. ↩

- AIbid., 343. ↩

- Harbich and Hassenzahl, “Beyond Task Completion in the Workplace,” 154–162. ↩

- Seale, Hicks, and Nicholson, “Towards a Critical Turn in Library UX.” ↩

- Weave: Journal of Library User Experience, 11, accessed April 15, 2024, https://journals.publishing.umich.edu/weaveux/. ↩

- Seale, Hicks, and Nicholson, “Towards a Critical Turn in Library UX,” 14. ↩

- ibid., p. 15. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid., 12. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid., pp. 14-15. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid., p. 13. Saffer cited in. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Thank you to Andrew Goffey for making this point while commenting on early draft. ↩

- Ruha Benjamin, Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2019), 174–80. ↩

- Benjamin, Race After Technology, 174–80. ↩

- Seale, Hicks, and Nicholson, “Towards a Critical Turn in Library UX,” 7. ↩

- Harbich and Hassenzahl, “Beyond Task Completion in the Workplace”; Sagi Gidali, “Office Design Matters More Than Ever: Using UX Principles Can Help,” Forbes, February 15, 2023, https://www.forbes.com/sites/allbusiness/2023/02/15/office-design-matters-more-than-ever-using-ux-principles-can-help/. ↩

- Don Norman and Jakob Nielsen, “Definition of User Experience (UX),” Nielsen Norman Group, last modified December 19, 2022, https://www.nngroup.com/articles/definition-user-experience/. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- The Nielsen Norman Group (NN/g) is a user experience (UX) research and consulting firm founded by Jakob Nielsen, Don Norman, and Bruce Tognazzini. They specialize in usability, user interface design, and other aspects of human-computer interaction. NN/g provides training, conducts research, and offers consulting services to help companies improve the usability and user experience of their products and services. ↩

- Don Norman, The Design of Everyday Things (New York: Basic Books, 1988). ↩

- Don Norman, Emotional Design: Why We Love (or Hate) Everyday Things (New York: Basic Books, 2007), 39. ↩

- Don Norman, “Don Norman: The Term ‘UX,’” YouTube video, 2:45, posted August 8, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9BdtGjoIN4E. ↩

- For influential and widely cited examples of popular emotional neuroscience see Antonio R. Damasio, Descartes’ Error (New York: Random House, 2006); Joseph E. LeDoux, The Emotional Brain: The Mysterious Underpinnings of Emotional Life (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1998). See the emotional turn in marketing in e.g., John O’Shaughnessy and Nicholas Jackson O’Shaughnessy, The Marketing Power of Emotion (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002); Marc Gobe, Emotional Branding: The New Paradigm for Connecting Brands to People (New York: Allworth Press, 2001). ↩

- Marc Hassenzahl, Michael Burmester, and Franz Koller, “User Experience Is All There Is: Twenty Years of Designing Positive Experiences and Meaningful Technology,” i-com 20, no. 3 (2021): 197–213. ↩

- Ibid., 200-01. ↩

- Ibid., 201. ↩

- Ibid., 197. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid., 198. ↩

- Heidi Marja Rasila, Peggie Rothe, and Suvi Nenonen, “Workplace Experience—A Journey Through a Business Park,” Facilities 27, no. 13/14 (2009): 486–496, at 486. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Martin E.P. Seligman and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, “Positive Psychology: An Introduction,” American Psychologist 55, no. 1 (2000): 5–14. ↩

- Harbich and Hassenzahl, “Beyond Task Completion in the Workplace.” ↩

- Ibid., 155. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid., 157. ↩

- Marc Hassenzahl, “Emotions Can Be Quite Ephemeral; We Cannot Design Them,” Interactions 11, no. 5 (2004): 46–48, at 47. ↩

- Harbich and Hassenzahl, “Beyond Task Completion in the Workplace,” 157 (italics added). ↩

- Ibid., 158. ↩

- Caleb Sponheim, Encouraging Flow State in Products, Nielsen Norman Group, YouTube video, 3:29, posted April 13, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c97hSXahVNI. ↩

- Harbich and Hassenzahl, “Beyond task completion in the workplace,” 158. ↩

- Ibid., 155. ↩

- Will Davies, “The Political Economy of Pulse: Techno-Somatic Rhythm and Real-Time Data,” Ephemera 19, no. 3 (2019): 513–536, at 527. ↩

- Ibid., 527. ↩

- Ibid., 527. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid., 530. ↩

- Ibid., 513. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid., 514. ↩

- Originally located on the Virgin Pulse website, “Reduce Your HR Admin,” accessed April 16, 2024, https://community.virginpulse.com/en-gb/reduce-your-hr-admin. Note: During the review process, documentation for a rebranded Virgin Pulse can be found at this website: accessed June 3, 2025, https://personifyhealth.com/. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Peter Mantello and Manh-Tung Ho, “Emotional AI and the Future of Wellbeing in the Post-Pandemic Workplace,” AI & Society (2023): 1–7. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Matthew McDonald and Jean O’Callaghan, “Positive Psychology: A Foucauldian Critique,” The Humanistic Psychologist 36, no. 2 (2008): 127–142, at 127. ↩

- Ibid., 127. ↩

- Martínez-Guzmán and Lara, “Affective modulation in positive psychology’s regime of happiness,” 338. ↩

- Davies, “The Political Economy of Pulse,” 529. ↩

- Martínez-Guzmán and Lara, “Affective Modulation in Positive Psychology’s Regime of Happiness,” 338. ↩

- Ibid., 337, 341. ↩

- Davies, “The Political Economy of Pulse,” 540. ↩

- Stephanie Alice Baker, “From the Wellness Movement to the Wellness Industry,” in Wellness Culture (Bingley, UK: Emerald Publishing, 2022), 41–73, at 65. ↩

- Davies, “The Political Economy of Pulse,” 541-42. ↩

- Steven Kolodziejski, “Create a Work Environment That Fosters Flow,” Harvard Business Review, May 6, 2014, https://hbr.org/2014/05/create-a-work-environment-that-fosters-flow. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Maral Babapour Chafi and Antonio Cobaleda Cordero, “Contextual User Research Methods for Eliciting User Experience Insights in Workplace Studies,” Future Workspaces (2020): 265–275, at 274. ↩

- Rasila, Rothe, and Nenonen, “Workplace Experience,” 489. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Chafi and Cordero, “Contextual User Research Methods,” 271. ↩

- K. Zeiner et al., “Designing for Positive User Experience in Work Contexts: Experience Categories and Their Applications,” Human Technology 14, no. 2 (2018): 140–175, https://doi.org/10.17011/ht/urn.201808103815, at 146, 156, 162. ↩

- Ibid., 142. ↩

- E. P. Thompson, “Time, Work-Discipline, and Industrial Capitalism,” Past & Present 38 (1967): 56–97, http://www.jstor.org/stable/649749; Paul Virilio, Speed and Politics (Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2006. ↩

- Seale, Hicks, and Nicholson, “Towards a Critical Turn in Library UX,” 15. ↩

- Hugo Reinert and Erik S. Reinert, “Creative Destruction in Economics: Nietzsche, Sombart, Schumpeter,” in Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900) Economy and Society (2006): 55–85. ↩

- Seale, Hicks, and Nicholson, “Towards a Critical Turn in Library UX,” 16. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Patricia Ticineto Clough et al., “Notes Towards a Theory of Affect-Itself,” Ephemera: Theory and Politics in Organization 7, no. 1 (2007): 60–77, at 73. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid., 70. ↩

- Martínez-Guzmán and Lara, “Affective Modulation in Positive Psychology’s Regime of Happiness, 346. ↩

- Seale, Hicks, and Nicholson, “Towards a Critical Turn in Library UX,” 16. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid., 16-17. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- According to a Big Tech version of responsibilization, a user’s concerns over where the blame lies for being duped by a dark UX pattern is transformed into a user responsibility, wherein being duped is just a consequence of a user desire for ease of use or the price paid for freemium. Colin M. Gray et al., “The Dark (Patterns) Side of UX Design,” in Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (2018), 10. ↩

- Martínez-Guzmán and Lara, “Affective Modulation in Positive Psychology’s Regime of Happiness,” 341. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- T.D. Sampson, The Struggle for User Experience: Birth, School, Work, Death (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, forthcoming 2026). ↩