Introduction

Many artists are dependent on popular audiovisual distribution platforms such as YouTube, Vimeo, Daily Motion and others. While Vimeo requires a paid subscription for fast streaming,1 Youtube has, until now, the largest participation since it offers free service for high speed streaming, (nonetheless with the insertion of advertisements). The platform has more revenue plans, including paid subscriptions for popular channels and for ad-free viewing,2 and in 2017 a live TV service streaming major broadcasters content became available in the US.3

The video hosting service launched in 20054 with all sorts of user-generated videos, which often attracted the participation of niche audiences. It was not long after being acquired by Google in 20065 that the platform became the most popular online video sharing provider, generating billions of dollars per year from advertisements and from data analysis.6 In the process of increasing their ad revenue, YouTube partnered with commercial media providers, and it deployed much stricter rules on copyright violations.7 The video platform started to automatically filter copyright on video uploads and either monetize or block copyrighted videos.8 That meant derivative content such as fan-works and mashups, as well as artists’ works would come into conflict with the business model of large media corporations.

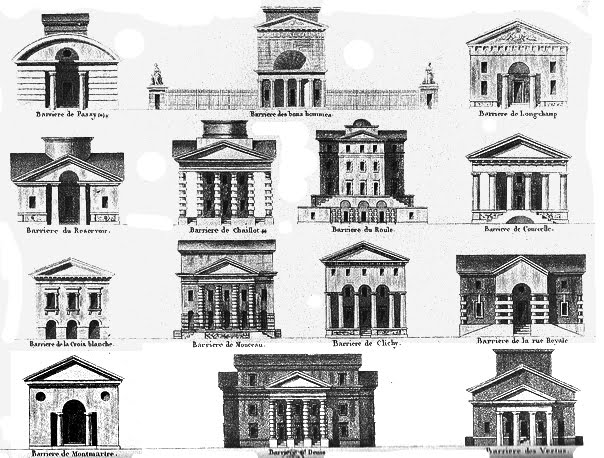

The art project Content Removed/Walls Installed9 was based on research conducted by John Colenbrander and myself, and it addressed the issue of YouTube’s cultural monetization and the enforcement of the copyright filter by drawing a metaphoric parallel with the tax wall around Paris in the 18th century.10 The art work illustrated the problem of copyright filtering but most importantly served as a methodology to interrogate YouTube’s algorithm and its implicit bias. With the help of a script I wrote, random geometric patterns were introduced into the frames of a video and surfaced aspects of how the (proprietary) software matched copyrighted content. I will elaborate on the art project and the difficulties of conducting research in a proprietary platform later in the paper. For now, I would like to introduce the YouTube Content ID filter.

Copyright Bots

Automatic content filtering for resolving copyright disputes has been enforced by some hosting services that deal with large numbers of uploads as an alternative form of dispute resolution system, one that could be quicker and less expensive than litigation.11 Based on the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA)12 of the United States, Internet and content services providers’ liability for copyright violations is limited if they remove infringing content expeditiously from their websites upon take down requests and consideration of available facts and circumstances. Both YouTube and Daily Motion web video platforms have been sued for late removal of infringing content in the past.13 Hence, the employment of software for filtering user-generated content once it is uploaded solves the issue of speed necessary for the companies to avoid lawsuits, but it does not solve the actual conflict between rightsholders and users in a number of cases, for example when it comes to fair use and educational copyright exemptions.

Such alternative dispute systems with the use of software deciding on good or bad content may be swift in their results and address a global public but they largely fail to handle the subtle difference between copyright take-down and censorship, or between fair-use content and copyright violations. They also fail to allocate interest-based claims between the parties, which is the primary principle and reason behind the dispute systems design originally introduced in the 1980s. An example of the impact of such rigid software dispute resolution occurred during the Hugo science fiction awards ceremony at Worldcon in 2012. Ustream online video service interrupted the annual awards’ live broadcasting with a copyright infringement flag when clips from Doctor Who series were displayed for the TV sci-fi nomination. The online streaming ended at that point with frustrated viewers resorting to twitter for any updates of the event.14

In an attempt to pre-emptively identify copyrighted material, YouTube offers its Content ID service to users with exclusive rights to content. For setting up as a content owner, users need to meet the eligibility criteria, which exclude works such as:

- Mashups, “best ofs”, compilations, and remixes of other works;

- Video game play, software visuals, trailers;

- Unlicensed music and video music or video that was licensed, but without exclusivity;

- Recordings of performances. (including concerts, events, speeches, shows)15

YouTube provides forms to be filled with Content ID requests and audiovisual content as references for their copyrighted material. Applicants can choose one of the possible remedies listed in the form: monetizing their copyright material with advertisement, and/or tracking content views in the platform, or completely blocking content. Following that, YouTube’s software can perform content analysis upon users’ video submissions and, in cases where a match is found, the video display respectively includes an advertisement or its content is blocked. With the implementation of the automated Content ID copyright filter there is no consideration of available facts and circumstances. In such a massive multi-user platform the number of videos that need to be scanned can be an impossible task. The Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) has suggested some precautions to eliminate the abuse of Content ID matching. Namely that the system should first send a warning rather than removing the content and that it should match the video and audio codecs as well as 90% and more of the duration of the original content before applying copyright restrictions.16

While the DMCA originates in United States law, and the Content ID filter reflects its provisions, such laws are not restricted to that country. The Electronic Commerce directive of the European Union has a similar legal provision for limiting liability on behalf of the intermediaries (hosting services, internet providers and in general what the directive calls “information society”. Article 14, paragraph 1 of the directive, states that providers have no liability in cases where they can have no knowledge of illegal activity and that upon obtaining such knowledge they have to expeditiously remove illegal information.17 Article 15 states that no monitoring of illegal activity is generally obliged by information society’s service providers.18 However on February 2017 the first draft of the commission’s new Copyright directive proposal was published, in which article 13 indicates that ‘Member States shall facilitate, where appropriate, the cooperation between the information society and rightsholders through stakeholder dialogues to define best practices, such as appropriate and proportionate content recognition technologies […]’.19 In other words, even though the Electronic Commerce directive doesn’t compel content monitoring, the commission wants to ignore that and require upload filtering. An information leak 20 from the European Council shows that not all Member States agree with users uploads being pre-emptively filtered because it would harm the single market, and would be against the human rights of European citizens. Therefore, the six countries that have serious doubts about the proposed Copyright reform have notified the Council’s legal service and await its assessment of the legality of Article 13.21

The United States media industry also appear to push for an analogous universal measure. In December 2016, the leading US recording industry companies wrote to the then president-elect Trump, pre-empting his scheduled meeting with tech companies, to reinforce support for ‘strong protection for intellectual property rights’ and demand that the ‘world’s most sophisticated technology corporations can do better – by helping to prevent illegal access and paying fair market value for music with prices set by or based on the free market’.22

The legal question at hand is whether algorithmic dispute systems should be employed in the first place for enforcing pre-emptive penalties and/or economic remedies automatically. DMCA gives the companies a mandate to take down content upon rightsholders’ notice in order to limit their liability for copyright violations. However, YouTube and other platforms that employ automatic copyright filtering, constantly check and decide which uploaded content should be accessible or not based on their algorithms, which establish a form of censorship.

Legal Context: origin of Dispute Systems Design (DSD)

A decade after the first appearance of DSD in the United States during the 1980s, which tried to systematize Alternative Dispute Resolutions, the internet and e-commerce had to come up with tools to deal with online conflicts. In the mid 90s the National Center for Automated Information Research (NCAIR) funded three projects to experiment with online dispute resolution (ODR). The Virtual Magistrate project developed between the NCAIR and the Cyberspace Law Institute facilitated emails between users and mediators and had a short 72-hour time-frame for responses.23 The other two experiments were the Online Ombuds Office developed at the University of Massachusetts, and the distance-separated-family-disputes resolution system developed by Maryland University.24 In 1999 eBay offered mediation to its users with a start-up company called SquareTrade, which had to deal with numerous disputes whose afflicted costs surpassed the small amount of money for which the disputes originated in the first place. SquareTrade came up with the solution of selling a seal to eBay sellers that would build trust between the users and the no-brand-names sellers. The sellers, by buying the seal, agreed to engage in resolving conflict disputes.25

Today e-commerce platforms have their own tools and processes to deal with online purchase conflicts.26 The model of mediating disputes resolution with face-to-face communication, which circumvented state involvement, needed to be adjusted to the possibilities of resolution within online communications. However, ODR practitioners have not developed a systematized design for the use of technology in online disputes resolution. Hence, I believe is important to look into the period when DSD was introduced as a standardized set of principles to resolve conflicts in real life.

In the 1970s Caney Creek Coal Mine was one of the many union mines protesting with wildcat strikes against the maximization of production and for disability benefits, among other issues. Widespread strikes across the United States had been going on for more than a decade organized at grass-roots level and by the rank and file of the unions. It was a sharp manifestation of class struggle during a turbulent period of economic and political turn to neoliberal policies and weakening of union leadership. The failure of the union leadership to defend miners’ rights, however, was one factor that marked the beginning in the decline of unionism in the years to come.27 In 1980 a group of legal scholar-practitioners were employed by the Caney Creek company to design a dispute resolution system based on direct mediation and negotiation between the parties that would replace the existing complaints’ procedure. Under the existing model, employees who had a dispute with their employers had to file for grievances in order to initiate an arbitration process that could take months to determine an outcome. Hence, striking was often the only means available to miners for immediate resolution of their conflicts. By replacing the long arbitration process, the employers sought a way to reduce the incentive to strike while maintaining control over production.

The new dispute resolution system did not only replace the conventional arbitration system but progressively took over the role of the unions. In his paper The miners’ strikes of 1977-78, artist and writer Adam Turl shows that, after months of striking mine workers returned to work without enthusiasm. Their employers had dropped their demand to fire strike instigators, but The Miner’s Health Fund was dismantled, which was a crucial setback. The author refers to the growing pressure by the bosses and the then federal government,28 alongside the failure of national union leadership to make demands, as the cause of the demoralisation of the workers’ struggle, which ended in a stalemate in 1978.29 However, in the particular instance of Caney Creek , the new system of dispute resolution was itself a decisive factor in undermining the power of unions and workers’ ability to make collective bargaining demands. The process that was recommended by the legal scholars Ury, Brett and Goldberg (UB&G), who were recruited as mediators in Caney Creek, was to consider not only the terms of the collective bargaining contract but mostly each party’s interests.30 It is important to highlight here the meaning of ‘interests’ in respect to individuals’ conditions and desires.31 Negotiating within a group of workers within one company instead of a union that represents the workers’ rights as a whole, it is faster but it lacks the foundation of a long-term general good of the working class. Small-scale demands can be fixed quickly with made concessions (monetary or power-based) to the workers demanding them, but this cannot create new regulations or laws for the well-being of the working class in a national level.

In order to gain the workers’ trust, the mediators went as far as spending time in the Creek mines and going fishing with the union representatives. Their proposed dispute resolution, although appearing to be neutral due to its systematized design, and more direct due to the mine company’s available mediation in negotiating each party’s demands, created an asymmetry of power between the company and the individual workers by circumventing the union’s role in the negotiating process. Based on their experience at the Creek mines UB&G elaborated on a set of methods and principles for resolving frequent conflicts in affected organizations, or industries, quickly and efficiently.32 Their outcome was first formalized in a book published in 1988. It introduces their research at the Caney Creek Coal Mine and how the skeleton of their resolution scheme could be applied to other contexts. The authors argued that there were three stages of resolving disputes: (i) by negotiating interests, (ii) by adjudicating rights (legal suits), (iii) by pursuing power options, such as strikes by workers or lockouts by management. The authors believed that interests-based resolution as an alternative to rights-based arbitration was less prone to becoming defiant and escalated into strikes and lockouts because it enabled a company to continue operating even though, or especially when, that company was failing in respecting the rights of workers (such as providing miners with adequate protective clothing rather than expecting them to provide their own, as was the case at Caney Creek).33 The method they outlined suggests that it was neutral because it was systematic, just as algorithms are assumed to be neutral, yet in both cases biases can be built into the design.

Design: Equal parties in the Dispute Resolution

DSD and alternative dispute resolution in general, expect that both parties in a conflict to benefit from the outcome of their negotiation.34 On the other hand, the YouTube video sharing service is not an e-commerce platform, nor does it have an employer-employed relation with its users. However, it is in the company’s business model to handle disputes if it wants to continue operating with advertisement revenue from copyrighted content. The Ippolita collective has written a book about Google’s economic model which is based on selling mostly ads, not products and on users who produce content and consume it.35 Value is added by participating in YouTube’s platform by commenting, rating, and community bonding. Google’s prime consideration is therefore to sell personalised data to advertisement agents.

The Content ID system adds an extra layer to YouTube’s profit-making, since it works behind bilateral agreements between YouTube and exclusive rights holders.36 While YouTube offers a disclaimer form available to users who disagree with enforced copyright claims, many have described the form-filling process intimidating since it requires users’ full contact details and warns them that rightsholders might respond by filing a lawsuit against the users.37 For example, a user who regularly uploads content with music scores released for free from companies such as purple-planet,38 or from public domain databases, accounts how often his content’s music was flagged as infringing, especially classical music scores, and had to counter-notify the copyright holders.39 Here it is worth noting that YouTube’s process of copyright notices and counter-notices is communicated via the platform and is no longer accessible after the dispute is settled.

The identification system also raises problems with remix and mashup works. If a remix work gets identified as content owned by third parties then the author of the remix work has no monetizing resources available on YouTube and similar rules apply to the other services such as Daily Motion. Furthermore, artists with derivative works have no means to apply for copyright management in the first place, since they do not own the exclusive rights to the work. Legal scholar, Valérie Benabou wrote an extensive report about remixed works (oeuvres transformative) in 2013 for the French council of literary and artistic property. In her report she explains the risks of the future of derivative works in the networked era of video services due to an adherence to traditional concepts of intellectual property whereas online technology demands new specifications both in the economic model and the distribution licences of authorship. She also raised the valid question of stifling marginalized derivative works by being blocked in centralized video platforms due to copyright infringement, while their cultural value is often appreciated later in time.40 What becomes clear then is that, apart from Content ID’s failure in respect of all parties’ interests in the settlement, cultural works of less popular genres (such as campy, trashy, parodies and fan culture) tend to get even more marginalized. Copies of books, vinyl records and cassette tapes could not be traced and censored in the past. In the 1980s The British Phonographic Industry developed an anti-copyright infringement41 campaign with a logo depicting a cassette tape in place of a skull, with crossbones below it, in order to warn consumers with the message that making copies of recordings, even for personal use, would be treated as piracy. Following this, in 1992 the personal computer boom brought about the next anti-piracy campaign by the Software Publishers Association Don’t copy that floppy42 with a music video clip.43 In the 2000s, the anti-copyright infringement movement was revived, this time against internet piracy.44

The last decade saw copyright protection embedded in the technology we use, either in the form of Digital Rights Management (DRM)45 or online content filtering bots. In 2017, after years of negotiations with media corporations and DRM advocates the World Wide Web Consortium folded and enabled browser encryption46 and playback control of media content by media owners.47 By allocating control mechanisms within technological tools and reducing political confrontation to the private sphere, the structure of the existing legal regime perpetuates outdated social biases.48

Effect: Inaccessible Files

When the government was on the road to Lodi, Pisa, Foggia, Lucera, Celano, or one of the other administrative castles, it reputedly was accompanied by dancing Saracen girls and animals unknown in Italy, such as carriers bearing the crown jewels and packhorses loaded with paper treasure, the scrinia. The latter was the name for mostly leather-covered woven chests, cases, and coffers containing files. Journeying through the country, the packhorses of Frederick’s menagerie put on display the state’s entire store of data.

– Frederick II’s ruling as king of Sicily and Holly Roman Emperor (1220 – 1250)49 Cornelia Vismann50

Big data companies attract investment and increase their market share by controlling access to their pools of user data. YouTube does not disclose its copyright registries and, their online information asserts that it is solely at the company’s discretion to accept copyright content registrations, positioning itself as the sole point of authority. The following is from YouTube’s copyright help website:

If accepted [by YouTube] to use the Content ID tools, applicants will be required to complete an agreement explicitly stating that only content with exclusive rights can be used as references. […] Content ID applicants may be rejected if other tools better suit their needs’ and ‘Do not make false claims. Misuse of this process may result in the suspension of your account or other legal consequences.51

While at first glance this policy may appear intended to prevent people form trying to scam money by randomly claiming ownership over other people’s content, there are a number of issues in practice. Exclusive rights over a work often means paying for any third parties’ work incorporated in the final work, or a work that has no other element from any other source. While ownership of a non transformative work is possible by companies and individual creators alike, mostly companies and corporations can afford to pay royalties to third parties in order to obtain exclusive rights. Therefore, while as a mashup artist you cannot apply for the Content ID tools, as a rightsholder company you can apply for either ad revenue, views analytics or both, from a mashup video which partly contains elements of your copyrighted material. Furthermore, YouTube’s decision process is not transparent, thus one cannot know on which grounds an application for the use of Content ID tools is rejected.

The process of registering copyright reference starts when a media company, or copyright holder, submits the online Content ID form and chooses which remedy they prefer for copyright violations (monetizing, view analytics, video removal). YouTube reviews the application and decides whether to grant permission for said rightsholder to send the copyrighted content, which will serve as a reference against already uploaded content and all future uploads on the platform. The criteria for applying for ContentID access is that ‘Applicants must be able to provide evidence of the copyrighted content for which they control exclusive rights’52. Applicants do not need to provide evidence while applying but should be able to do so if asked. The Content ID sign-up form is one page which simply asks applicants for their full name, country, type of works they want to register, what they want to do with Content ID, why they want to participate in the system and a list of the copyrighted works they wish to reference. There are other tools for rightsholders, namely the Content Verification Program53, which provides a search form to find infringing material, and the Copyright Infringement Notification (take-down notice). These tools can be suggested by YouTube as alternatives to Content ID registration, or users can apply for accessing those tools with an online form similar to that for Content ID. The simplicity of these forms contrasts with the US copyright office’s methods for whom the copyright registration for audiovisual works is a 22-page web-form (plus the ability to download a preview).54

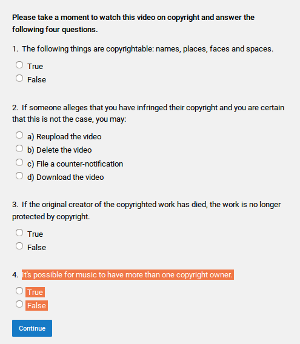

The video sharing platform does not explain on which grounds decisions are made, who makes those decisions, or which legal framework is consulted when Content ID applications are reviewed. Moreover, YouTube adopts an authoritative profile by terminating accounts that have been flagged three times with copyright infringements (the company calls them ‘copyright strikes’)55 and requires everyone who wishes to restore their accounts to complete Copyright School.56 The latter term coined by YouTube refers to the process of a multiple-choice test asking for instance, ‘It’s possible for music to have more than one copyright owner?’ or whether names and faces can be copyrightable, among other trivial questions.57 The system tries to train the user according to YouTube’s interpretation of copyright law by adapting simple forms of questionnaire as a corrective procedure for ‘offending’ users to regain back access to their accounts.

Seen in relation to their eligibility criteria, in which mashups and remixes are not legible for claiming authorship,58 YouTube’s copyright formation establishes remuneration based on ownership rather than authorship and favours speed and simplicity of process over rigour. Their system for evaluating content, therefore, falls short of legal scrutiny.59

These sets of tools create a registry of copyright records that is privately owned by a corporation and is inaccessible to others. They are developed for the benefit of exclusive rightsholders even though hard evidence of these rights are not required in the application. Which jurisdiction, convention or legal treaty is applicable in YouTube’s application is not stated anywhere in the copyright support section of the website. In contrast, the US Copyright Office website for copyright registration links to and cites all legal references that are applicable to the copyright claim60 and includes remix works under Performing Arts category for copyright registration.61 An otherwise complex legal procedure which should take into account the copyright law of the country of origin of either the author, or the company that has bought the exclusive rights, or the location of the work’s first publication, and the country’s partnership in any international treaties, is reduced to a few questions in YouTube’s copyright-management forms.62

The determination of applicable law based on the work’s country of origin or the work’s first publication, is itself a complex issue. The court case Moberg vs 33T addresses exactly this. In 2007, Moberg, a photographer artist, filed his complaint against United States’ corporation 33T for unauthorized distribution of his photographs, which were first published on a German commercial gallery website. 33T defended itself against the plaintiff’s claim arguing that the court lacked subject matter jurisdiction to proceed with the case because a “United States work” must be registered prior to the filing of a civil action for copyright infringement. In other words 33T claimed that a United states court did not have the authority to hear this dispute at all because the US Copyright Act required that intellectual works originated in the United States should register copyright protection before the rightsholder could claim an infringement.63 The court, however, decided that Moberg’s photographs had been published in a German website and intended for a German public. Even if they were online they were not published simultaneously in the United States so the photographs were not simultaneously a United States’ work but solely a German work and therefore the US legal clause for compulsory copyright registration did not have effect. On that ground, the court had the authority to hear the case and ruled that 33T was indeed infringing copyright.64

The Content ID software system requires a simplification of legal reasoning up to the point that it can be performed by an automatic process. This enables the reduction of the Copyright Office’s long application into a single online form and can perform continuous automated copyright checks on years of uploaded content (for every new copyright reference, YouTube’s filter executes the matching algorithm for all videos in its database, and for every new video, the algorithm checks back all copyright references). Consequently, YouTube has succeeded in creating a large pool of copyright references that no one outside the corporation has access to. In contrast, on the US Copyright Office website we read: ‘Please be aware that when you register your claim to a copyright in a work with the US Copyright Office, you are making a public record. All the information you provide on your copyright registration is available to the public and will be available on the Internet.65 While YouTube behaves as if it is a state administration, its records are sealed off the public making it difficult to challenge or hold publicly accountable for any copyright misjudgements. An academic research request to YouTube’s contact email asking for a sample of their dataset used in the Content ID system, triggers an automatic reply with a link to Google’s latest newsfeed.66

According to YouTube’s Terms of Service, the company can delete an item from its database at any time for any reason.67 What follows is that the corporation can profit from its records as long as it sees fit without being accountable to rightsholders or users alike. The authority of YouTube’s file-keeping system, which handles copyright claims, suggests that the fee the company collects from advertisement is comparable to taxation on goods. On their website page about user-generated earnings, YouTube informs the user that: ‘There are no guarantees under the YouTube partner agreement about how much, or whether, you will be paid. Earnings are generated based on a share of advertising revenue generated when people view your video – so more views may lead to more revenue.68 Again how much of this share goes to the company and to the rightsholders is not disclosed.

From copyright content management to advertisement revenue, all happen within a closed system. By registering files as references of copyright material in the Content ID, YouTube treat these files as proof of copyright and at the same time as a representation of copyright certification. However, in the territory to which YouTube refers legal recourse, these files are disconnected from the legitimate source that issues such certificates, the Copyright Office of the United States. Further, copyright registration is not required in all countries, and the Berne Convention declares that copyright is automatically applicable when a work is fixed to a medium.69 The copyright registry of YouTube, which relies on provided content by rightsholders without them providing legal proof of copyright, is thus disconnected from the source of legal transmission, that is the authority issuer, and so exploitation and discrepancy is inevitable. This is an example of how monopoly tech platforms take on small parts of the state, whose aspects I will discuss later in my paper.

In her book Files. Law and Media Technology,70 Cornelia Vismann explains how after the fall of the Roman Empire, central administrations started to decline and during the 6th century and early medieval times, documents replaced public-record taking and they were created to be distributed without keeping copies in a central registry.71 As a result, forgeries and false certificates thrived, as did the difficulty of tracing the issuer, creating a range of ownership rights based on customs and old titles. The discipline of diplomatics, which was invented in the 1680s,72 focused on ascertaining the originality of the documents (diplomas, writs, certificates) and led to an underestimation of the source transmitting the law (chanceries) because its examination model was based on the form of the document – whether its elements were original – while the administrative processes, ‘the transmission medium itself remains a blind spot of legal history’.73 Much later, historians and librarians started to include the context of which chanceries, or later, state registries had issued a document as a method to verify the legality of documents.74

Cultural Monetization: Remix and Derivative Works

The curtain having descended on the solemn business of law at the end of the day’s sitting, it rose again in the off hours to display the farce’s carnivalesque inversion of the legal realm: a world not of sense but of nonsense, populated not by reasonable persons but by fools, concerned not with honourable representation but with fraudulent misrepresentation, ruse, and deceit.

‘The Love of the Censor’, Stephanie Lysyk 75

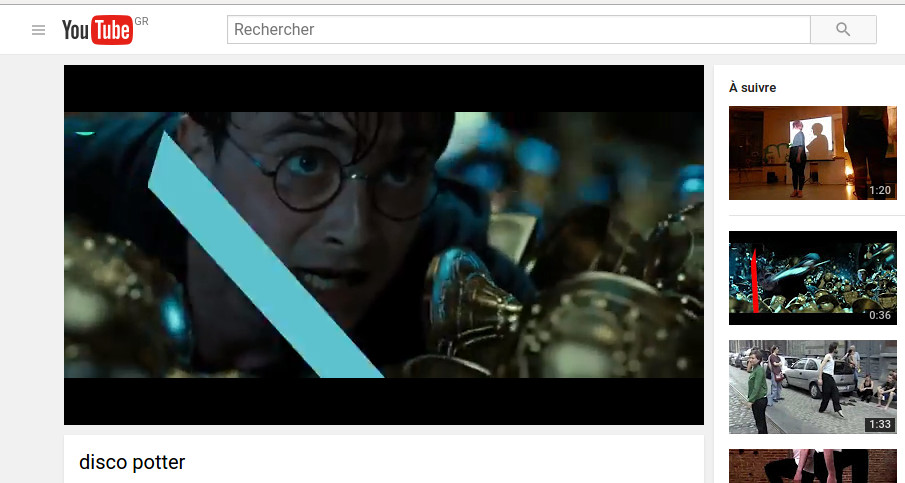

As mentioned at the beginning of this paper, a key problem in doing research on proprietary platforms is that they do not give access to their records nor to the source code of the algorithms they implement for their services. Google does not disclose information about their dispute resolution methods nor software. Moreover, they erase any dispute records on Youtube’s user dashboard as soon as the matter is solved. During the development of the art project Content Removed/Walls Installed, I developed a form of ‘reverse engineering’ of YouTube’s dispute resolution algorithm. In general, this process involves a controlled set of input data and an observation on how the algorithm responds differently to each type of input, from where one should be able to make some inferences about how the algorithm works. With the aid of a script I wrote, I visually edited an extract of a Harry Potter film by introducing randomly generated geometric shapes on each frame of the video – similar practices, like adding overlay pixels or split image frames in videos, are quite common practice with people posting videos to YouTube wanting to avoid copyright strikes76 -. The purpose was to test the sharpness of the pixel-matching algorithm, which YouTube uses when a video is uploaded on their platform. This video was not flagged as copyrighted by third parties and no advertisement was attached. However the same video with a 10-second extension of untouched Harry Potter extract was monetized. I didn’t receive any notice about the advertisement, it was automatically added as a banner on the video itself.77 Here I would like to add that the artistic research was conducted during our residency at the Belgian Media Art Association Constant in 2014. During the writing of this paper in 2017, YouTube under pressure of their major advertisement partners wanting to disassociate any extremist content with their brands, have restricted monetization to videos with less than 10.000 views. Through their announcement they inform that all channels above that threshold will be reviewed so to ensure that their content match YouTube policies.78

The art research was presented in the context of walls and taxation with a reference to the Farmers-General Wall of Paris, which were built and managed by private companies (tax farmers)79 for the collection of tolls on goods before entering the city. The wall was built in 1784 by renown French architect Ledoux and was the first wall intended to collect taxes instead of protecting the city from invaders. It comprised of sixty monumental tax-collection offices ringing Paris, and naturally it was a major cause and symbol of the French Revolution (while surprisingly Ledoux escaped the guillotine).80 The ferme générale was thus an indirect tax operation collecting duties on behalf of the king, and charging heavy bonus fees for themselves.81 Having been a symbol of unjustinjust tax under the Ancien Régime, the wall served as a juxtaposition to YouTube’s monetization on behalf of third parties copyright owners in our artistic research.

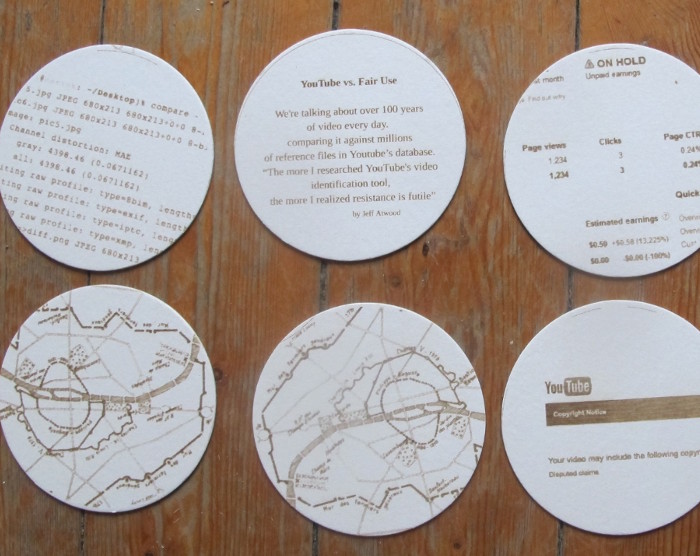

The presentation took place at an art space82 in Antwerp, in 2014. The project transformed the bar into a legal consultancy service and stocked the bar with beer mats, bottle labels and card reservations on which we printed Parisian 18th century taxes (e.g. gabelle; tax on salt), YouTube’s Content ID forms, and code snippets of the script used in the art research. In this way the bar’s pronounced tax system helped to explain virtual forms of taxation and indirect pay-walls produces by YouTube’s cultural monetization processes.

The two Harry Potter extracts were projected while discussing YouTube’s monetization policies. It came to our attention that musicians had conflicts with other bands that claimed their sound as copyrighted and were hesitant to dispute this. A film-maker who was about to launch their own travelling footage asked for advice in dealing with the possibility of copyright infringement. On the other hand, non-artist audience members thought monetization was a way to contribute for an otherwise free service.

As I mentioned earlier, Google’s business model relies on advertisement in order to provide their products for free, which has enabled it to build a market-dominating position and to extend its influence on media, knowledge and culture. The US social policy think-tank New America83 dismissed one of its research group in June 2017 when the group published a letter of support for a European antitrust ruling against Google. Since 2000, the then CEO of Google and Google Inc. have contributed funds to the foundation, which they threatened to cut off on the day the antitrust support letter appeared on the New America’s website.84

Perhaps the economic model advertisement-in-exchange-for-free-service is acceptable for the capitalist system, but it has deeper implications in that it creates oligopolies. By attracting the majority of consumers/users with free services, and dominating the market as a result, private corporations build influence in other aspects of life such as politics, knowledge and innovation. Google’s dominance and that of other information technology companies alike, are also built on exploiting the free and open source software community. Google’s ‘beta’ versions of its services, and summer schools are hefty examples of that model; coders contribute significantly to the development of the beta services through their feedback, or contribute code in exchange of boosting their CVs or earning an award at Google summer schools.85 With artist residency programs86 and free knowledge courses being the most recent developments of this model, Google expands its influence in culture and knowledge production.87

In his book The Stack, Benjamin H. Bratton is concerned about platform wars over legal identity, currency and infrastructure between web corporations and states, which establish a cloud feudalism and cosmopolitanism at the same time. States become cloud platforms and clouds become states, he writes, meaning that public and private realms have become an amalgam of power that creates partial polities. These cloud polities interweave with state claims and, more and more, state facilities are served by cloud applications since they have become easier to use amidst the non-stop online connectivity.88 However the emerging role of cloud services in daily life has not weakened the power of the state as some neoliberals were hoping in the 1970s (and arguably even now with the allure of bitcoin and the darknet). What is happening is that cloud corporations and states – the latter by using cloud web platforms for services such as open data government or cybersecurity –89 reinforce each other with omnipresent forms of ambient government, generating a new order, which spawns more borders, not fewer.90

Thus, Bratton concludes that territorial jurisdiction is in crisis with the overlapping of national and international laws, terms of services in networked locations, and data servers’ physical locations. The result is a cloud polis that hosts entire cultures, economies, religions making an alternative geopolitics whose mode of governance is messy and conflictual.91 Bratton continues by indicating that the risk is the point where a state’s policy cannot be enforced on corporations due to their ubiquity and life’s practical interdependence on the latter.92 Moreover cloud platforms (Google, Facebook, Amazon) take advantage of their networked power and oligopoly in order to create their own terms that fit their economic profits without having to be accountable either to their users or to states.

Conclusion: Quasi-institutions and the Public Good

So far I have discussed the inequalities between the interested parties in the Content ID system, the failures in the grey zone of fair use and derivative works, and how economic and political power can be concentrated in proprietary file registries and databases. I would like to close with some reflections on the stake of the public interest when it comes to design dispute systems in general, and the development of software for dispute resolutions in particular.

Amy J. Cohen writes in her paper about Dispute System Design and Neoliberalism,93 that DSD was developed in the 1970s, a time when our relation to the state was different from today because solutions to conflicts were given by law and politics rather than the markets. She informs that ‘contemporary dispute resolution scholars are transforming alternative principles for managing individual disputes into principles for managing larger-scale conflict’ while state power has been undergoing major shifts due to neoliberal policies in the US and abroad.94 She further explains that application of DSD to a negotiation between companies and people may enhance the ability of parties to negotiate with each other, but it also suppresses their crucial differences; the two entities do not have the same qualities, needs, emotions or the same legal resources. Furthermore, they have different access to legal expertise and insecurity towards litigation costs incurred by a possible court case.95 She gives the example of land pollution where companies trade-off regular pollution audits of the affected population with funding for community projects.96

Cohen notes that neoliberal policies of modern states have not just deregulated the financial markets and privatized public institutions. Since the Reagan administration in the United States, the participation of both ordinary citizens and private entities in the federal rule making has allowed public interest to come secondary to the interests of the negotiating parties, and has led to a dramatic regulatory flux and a hike in the socio-economic inequality.97 She is therefore concerned whether DSD is participating, deliberately or not, in neoliberal projects and highlights the necessity for dispute designers to research the social context of each case they undertake, in order to visualize solutions that include the general social good, instead of merely looking at the interests of each party involved.98 Without social analysis, she claims that DSD would continue to operate with a neoliberal bias because extra-legal dispute resolutions tend to adopt market values in resolving social conflicts almost by reflex.99

In the case of Content ID dispute resolution, the broader set of actors is not considered. YouTube has designed a dispute resolution system without taking into account fair use and derivative works because its technology design has no accountability obligations since it is not audited by any public institution (on legal or coding grounds). Shielded behind the DMCA’s requirement for rapid take-down of infringing material, the company has built a system to answer rightsholders’ demands automatically and as fast as new content is uploaded. Without state intervention, the company took this provision further to maximize profit on the back of its users, diminishing any grey areas of copyright law, and developing a biased DSD, along with an extensive but proprietary database of copyright reference material.

The corporate database becomes, therefore, a legitimate authority, similar to the quasi-institutions of 17th-18th century state secretaries, which were elevated to a tool of governance and which administered through the use of formalities (language, standardized letters) and by-passed the legal jurists. Vismann highlights the importance of secretaries, who ‘convinced themselves that they were superior to jurists & rhetorically schooled “constitutional lawyers”, and strove to render superfluous all unnecessary specialized legal experts’.100 Google’s meta-administration becomes very powerful since these databases are inaccessible to the public. YouTube, owned by Google, which also owns a huge digitalized books repository, employs the necessary software programmers and computing capital to run a comparison of every new uploaded video to each copyright reference in its Content ID database in a matter of minutes. It handles copyright claims and applications for Content ID partnership in a matter of weeks. By contrast, the copyright registration process at the US Office can take from 6 to 8 months. Google has taken on aspects of a global corporate state within national states, with the monetizing power to circumvent local and international law, and produces its own simplified system of jurisdiction and economic compensation. The modern state has not the economic and technological resources (or does not want) to provide a protective umbrella for cultural diversity and sharing. Private institutions, at first appearing as benevolent investors, take over cultural distribution, yet in the longer term they make large profits by locking down culture outside of the public good.

In the European Union, things start to look more sinister. It appears as the European Commission caves into the lobbying of media industries aiming to bake copyright-tracking into the internet. A draft proposal for Copyright reform, which in a nutshell, take DMCA law even further and requires a priori filtering mechanisms like Content ID for all media uploads to the internet was proposed in late 2017.101 At a time when politicians and private companies alike demand for fake news and terrorist content to be filtered and removed from social media, the only viable answer is the principle of net neutrality.102 Content should not be filtered by hosting services, because this only brings more censorship and renders the borders of what should be legitimate content or not susceptible to both the politics of state authorities and market oligopolies at each given time.

Notes

- “Upgrade Plan,” Plans, Vimeo, accessed September 10, 2017, https://vimeo.com/upgrade. ↩

- “YouTube: Revenue,” Wikipedia, last modified March 6, 2018, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/YouTube#Revenue. ↩

- “YouTube TV,” YouTube, accessed November 29, 2017, https://tv.youtube.com/welcome/. ↩

- Megan Rose Dickey, “The 22 Key Turning Points In The History Of YouTube,” Business Insider, February 15, 2013, http://www.businessinsider.com/key-turning-points-history-of-youtube-2013-2#chad-hurley-registers-the-trademark-logo-and-domain-of-youtube-on-valentines-day-2005-1. ↩

- On October 9, 2006, Google Inc. announced its agreement to acquire YouTube for $1.65 billion. YouTube would retain its operation independently to reserve its brand and community. See “News from Google,” Google, October 10, 2006, https://googlepress.blogspot.gr/2006/10/google-to-acquire-youtube-for-165_09.html. ↩

- Google does not disclose their revenue from YouTube, however financial and stock analytics showed an income of $8.5 billion in 2015. See Geoff Weiss, “Analyst: YouTube Estimated To Have Revenues Of $27 Billion In 2020”, tubefilter, April 15, 2016, https://www.tubefilter.com/2016/04/15/youtube-estimated-revenues-27-billion-2020/. ↩

- YouTube, closing their acquisition negotiations by Google, announced new partnerships with Universal Music Group, CBS Corp. and Sony BMG Music Entertainment. Similar arrangement announced before with Warner Music Group Inc. See The Associated Press, “Google buys YouTube for $1.65 billion,” NBC NEWS, last modified October 10, 2006, http://www.nbcnews.com/id/15196982/ns/business-us_business/t/google-buys-youtube-billion/. ↩

- YouTube launched the beta of their automate copyright filter in 2007, a year after company was acquired by Google. See “Latest Content ID tool for YouTube,” Official Blog, Google, October 15, 2007, https://googleblog.blogspot.gr/2007/10/latest-content-id-tool-for-youtube.html. ↩

- Artists: Maria Karagianni, John Colenbrander. Extra City gallery, Antwerp, January 2014, http://mara.multiplace.org/content-removed-walls-installed/. ↩

- The Wall of the Ferme générale was built between 1784 and 1791 by the Ferme générale (General Farm), the corporation of tax farmers. It was one of several city walls of Paris built between the early Middle Ages and the mid 19th century. See “Wall of the Farmers-General,” Wikipedia, last modified June 8, 2017, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wall_of_the_ Farmers-General. ↩

- Daily Motion is another video platform that uses copyright detection similar to YouTube. From their website: ‘Dailymotion works with Audible Magic and INA to provide content protection systems based on digital audio and video fingerprints. As a content owner, you can use one or both of these companies by giving them your content’s digital fingerprints. All videos uploaded on Dailymotion are matched against the INA and Audible Magic audio and video fingerprint databases. Every time we detect a match, we block the video before its publication on the site. If you want to be introduced to either INA or Audible Magic, please contact your content manager or contact the support team through the dedicated support form.’ See “Protect Your Copyright with Fingerprints,” Help Center, Dailymotion, last modified April 8, 2018, https://faq.dailymotion.com/hc/en-us/articles/203921173-Protect-Your-Copyright-with-Fingerprints. ↩

- Particularly the safe harbour provisions at §512(c) ‘Information Residing on Systems or Networks at the Direction of Users’ foresees that ‘upon notification of claimed infringement as described in paragraph (3), responds expeditiously to remove, or disable access to, the material that is claimed to be infringing or to be the subject of infringing activity.’ See “17 U.S. Code § 512 – Limitations on liability relating to material online,” Legal Information Institute, accessed April 10, 2018, https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/17/512. ↩

- Google was sued by Viacom. See Matt Marshall, “Audible Magic’s copyright filtering technology not working,” VentureBeat, June 8, 2007, http://venturebeat.com/2007/06/08/audible-magics-copyright-filtering-technology-not-working/. Daily Motion was sued by the private national French TV channel TF1. See Andre Yoskowitz, “Dailymotion fined for copyright infringement in France,” news by afterdawn, December 8, 2014, http://www.afterdawn.com/news/article.cfm/2014/12/08/dailymotion-fined-for-copyright-infringement-in-france. ↩

- Annalee Newitz, “How copyright enforcement robots killed the Hugo Awards,” GIZMODO, March 9, 2012, https://io9.gizmodo.com/5940036/how-copyright-enforcement-robots-killed-the-hugo-awards. ↩

- “Youtube Content ID eligibility,” YouTube, Google Support, accessed March 25, 2018, https://support.google.com/youtube/answer/1311402. ↩

- “Fair Use Principles for User Generated Video Content: Filters Must Incorporate Protections for Fair Use,” Electronic Frontier Foundation, accessed March 25, 2018, https://www.eff.org/pages/fair-use-principles-user-generated-video-content. ↩

- Directive 2000/31/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 8 June 2000 on certain legal aspects of information society services, in particular electronic commerce, in the Internal Market (‘Directive on electronic commerce’), Article 14 states: Hosting 1. Where an information society service is provided that consists of the storage of information provided by a recipient of the service, Member States shall ensure that the service provider is not liable for the information stored at the request of a recipient of the service, on condition that: (a) the provider does not have actual knowledge of illegal activity or information and, as regards claims for damages, is not aware of facts or circumstances from which the illegal activity or information is apparent; or (b) the provider, upon obtaining such knowledge or awareness, acts expeditiously to remove or to disable access to the information. 2. Paragraph 1 shall not apply when the recipient of the service is acting under the authority or the control of the provider. 3. This Article shall not affect the possibility for a court or administrative authority, in accordance with Member States’ legal systems, of requiring the service provider to terminate or prevent an infringement, nor does it affect the possibility for Member States of establishing procedures governing the removal or disabling of access to information. ↩

- Directive on electronic commerce, Article 15 states: No general obligation to monitor 1. Member States shall not impose a general obligation on providers, when providing the services covered by Articles 12, 13 and 14, to monitor the information which they transmit or store, nor a general obligation actively to seek facts or circumstances indicating illegal activity. 2. Member States may establish obligations for information society service providers promptly to inform the competent public authorities of alleged illegal activities undertaken or information provided by recipients of their service or obligations to communicate to the competent authorities, at their request, information enabling the identification of recipients of their service with whom they have storage agreements. ↩

- Diego Naranjo, “Lead Parliamentarian for Culture Committee defends upload filtering,” EDRi, published February 15, 2017, https://edri.org/lead-parliamentarian-culture-committee-defends-upload-filtering/. ↩

- At the time of the writing the proposal was not not yet officially presented, but copies were leaked. A note (in pdf format) published by Statewatch shows that EU governments of Belgium, the Czech Republic, Finland, Hungary, Ireland and the Netherlands have asked the Council’s Legal Service whether the proposal is compatible with EU law. The note, sent to the Legal Service on 25 July, asks: ‘Would the standalone measure/ obligation as currently proposed under Article 13 be compatible with the Charter of Human Rights (and more specifically Article 11- freedom of expression and information, Article 8 – Protection of personal data – and Article 16 – Freedom to conduct a business) in the light of the jurisprudence of the CJEU that aims to secure a fair balance in the application of competing fundamental rights? Are the proposed measures justified and proportionate?’ See “Copyright Directive: six Member States question legality of proposals for automated upload filtering ↩

- Communia Association, “Member States to Commission: We don’t trust your claims that censorship filters are in line with EU law,” Communia, published September 9, 2017, https://www.communia-association.org/2017/09/05/member-states-commission-dont-trust-claims-censorship-filters-line-eu-law/. ↩

- Record companies including ASCAP, BMI, A2IM, NMPA, SoundExchange and more. See Mike Masnick, “Legacy Recording Industry To Trump: Please Tell Tech Companies To Nerd Harder To Censor The Internet,” Techdirt, published December 14, 2016, https://www.techdirt.com/articles/20161213/18060136266/legacy-recording-industry-to-trump-please-tell-tech-companies-to-nerd-harder-to-censor-internet.shtml. ↩

- David Loundy, “Virtual Magistrate becomes a reality, sort of,” Chicago Daily Law Bulletin (June 13, 1996): 5, http://www.loundy.com/CDLB/Virtual-Magistrate.html. ↩

- Orna Rabinovich-Einy and Ethan Katsh, “Technology and the Future of Dispute Systems Design,” Harvard Negotiation Law Review journal 11 (Spring 2012): 165, http://www.hnlr.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/151-200.pdf. ↩

- Ibid. 167-170 ↩

- For example at present Ebay has a ‘Resolution Center’ where customers can ask refunds or replacement of their putchases. See “Resolution Center,” Ebay, accessed March 25, 2018, https://resolutioncenter.ebay.com/. Amazon has a ‘Return Center’. See “Amazon Returns,” Amazon, accessed March 25, 2018, https://www.amazon.com/gp/orc/returns/homepage.html. ↩

- Adam Turl, “The Miners’ Strike of 1977-78,” International Socialist Review journal 74, (2011), http://isreview.org/issue/74/miners-strike-1977-78. ↩

- Towards the end of his article, Turl notes that 3 years later the strikes as a form of labour protest in general came to a decisive end when President Ronald Reagan fired striking air traffic controllers in 1981 ‘signalling a new era in which business and government were to be even tougher on organized labour’. He quotes JoeAllen who wrote about Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organisation (PATCO): ‘In the year following his election, Reagan continued a policy, begun under the ousted Carter administration, of stalling in contract negotiations with PATCO, while putting everything in place to break them if they decided to strike. PATCO members had decided that they had had enough, and voted to strike-even though, as federal employees, they were barred from striking and faced possible dire consequences. “The strike is a result of frustration that’s been building up for years,” PATCO striker Robert Devery told Business Week in 1981. “We’re not on strike over money. People are tired of being dumped on, and they want to make it to retirement.” Stress is the main cause of illness and death for controllers, as they juggle the lives of thousands of airline passengers every day.’ See Joe Allen, “Patco’s Twenty-Fifth Anniversary: Return To Work Or You’re Fired,” International Socialist Review journal 49, (October 2006), http://isreview.org/issues/49/patco.shtml. ↩

- Turl, “The Miners’ Strike: The strikes end”. ↩

- James E. Westbrook, “Book Review Essay,” review of Getting Disputes Resolved by William B. Ury et al, Journal of Dispute Resolution (1989), http://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/jdr/vol1989/iss/15. ↩

- In his paper about Interests, Rights and Power, Maiese explains: Interests are the needs, desires, concerns, and fears that underlie people’s positions … Rights are independent standards of fairness or legitimacy that are either socially recognized or formally established in law or contract. Such standards include reciprocity, precedent, equality, and seniority. Finally, power can be understood as the ability to coerce someone into doing something he would not otherwise do. Exercising power is typically a matter of imposing costs on the other side or threatening to do so, whether through acts of aggression or withholding the benefits that derive from a relationship. See Michelle Maiese, “Interests, Rights, Power and Needs Frames,” Beyond Intractability, September 2004, http://www.beyondintractability.org/essay/interests-rights-power-needs-frames. ↩

- Eric Brahm, Julian Ouellet, “Designing New Dispute Resolution Systems,” Beyond Intractability, September 2003, http://www.beyondintractability.org/essay/designing-dispute-systems. ↩

- William B. Ury, Jeanne M. Brett, Stephen B. Goldberg, Getting Disputes Resolved: Designing Systems To Cut The Costs Of Conflict, (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1988). ↩

- Dispute System Design (DSD) was initially conceptualized with the view that equal parties could negotiate for their interests with the lowest costs inflicted. In cases where the outcome could not be equally attained, the solution was to render the initial object of conflict to a secondary source of interest where both parties by investing more would gain a satisfactory output for all. A proverbial ADR example tells how two sisters fighting over an orange are advised by the dispute resolution mediator to transform their primary ends (the orange) into secondary ends such as making a juice or baking a cake. The sisters can then satisfy their interests through secondary means, e.g the juice, the pulp. See Amy J. Cohen, “Dispute Systems Design,” Harvard Negotiation Law Review, (Winter 2009):63. Content ID’s object of conflict is authorship and the royalties attached to it, namely copyright for the Anglo-Saxons, or Droits d’Auteur (Authors’ rights) for the French. YouTube’s Content ID does indeed turn copyright to a secondary source of benefit by generating income from advertisement tagged on copyrighted videos, while videos remain accessible online. ↩

- Ippolita, The Dark Side of Google, trans. Patrice Riemens (Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2013), 76-78. ↩

- YouTube held a summit for its top 100 video personalities, and networks to discuss declining ad revenue due to new filters the platform introduced to combat ads appearing next to abusive video content. See Sahil Patel, “The ‘demonetized’: YouTube’s brand-safety crackdown has collateral damage,” Digiday UK, September 6, 2017, https://digiday.com/media/advertisers-may-have-returned-to-youtube-but-creators-are-still-losing-out-on-revenue/. ↩

- YouTube on their help website for counter notification basics states: Please note that when we forward the counter notice, it will include the full text of the counter notice, including any personal information you provide. The claimant may use this information to file a lawsuit against you in order to keep the content from being restored to YouTube. “YouTube Counter Notification,” Google Support, accessed March 29, 2017, https://support.google.com/youtube/answer/2807684?hl=en ↩

- “Royalty Free Music,” Purple Planet Music, accessed March 29, 2017, http://www.purple-planet.com/. ↩

- User Spyridon Kakouris had several times counter notified copyright claims for scores he had obtained from the public domain, e.g. classical music recordings performed by the U.S military band that can be found on the website of Purple Planet Music. His last copyright dispute on March 10 2017 (for his video at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eQcgyNger3g) went as following: ‘Hi Spyridon Kakouris, A copyright owner using Content ID claimed some material in your video. This is just a heads up Don’t worry. You’re not in trouble and your account standing is not affected by this. There are either ads running on your video, with the revenue going to the copyright owner, or the copyright owner is receiving stats about your video’s views. Video title: Ailiroy/Pastel-Dreams’ Kimono photoshoot Backstage I – Outside shoot Copyrighted content: Lady Kuan Yin: Karma and Past Lives Claimed by: CD Baby.’ And after his counter notice, YouTube replied: ‘Hi Spyridon Kakouris, Good news! After reviewing your dispute, CD Baby has decided to release their copyright claim on your YouTube video. Video title: “Ailiroy and Pastel-Dreams’ Kimono outside photoshoot Backstage” – The YouTube Team.’ Spiridon Kakouris, Facebook message to author, March 29, 2017. ↩

- Valérie Laure Benabou and Fabrice Langrognet, “Rapport sur les oeuvres transformatives,” Conseil Supérieur De La Propriété Littéraire Et Artistique, Paris, December 24, 2014, http://www.culture.gouv.fr/Thematiques/Propriete-litteraire-et-artistique/Conseil-superieur-de-la-propriete-litteraire-et-artistique/Travaux/Missions/Mission-du-CSPLA-relative-aux-creations-transformatives. ↩

- “Home Taping Is Killing Music,” Wikipedia, last modified March 20, 2018, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Home_Taping_Is_Killing_Music. ↩

- “Don’t Copy That Floppy,” Wikipedia, last modified March 2, 2018, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Don%27t_Copy_That_Floppy. ↩

- “Don’t Copy That Floppy,” Official Video, YouTube, accessed September 15, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=up863eQKGUI. ↩

- Copyright concerned industries have turned against service providers and software distributors as indirect infringers, rather than pursuing Internet users, and demand to expand copyright law to penalize them. “Copyright Infringement,” Wikipedia, last modified April 11, 2018, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Copyright_infringement. ↩

- “Digital Rights Management,” Electronic Frontier Foundation, accessed September 15, 2017, https://www.eff.org/issues/drm. ↩

- “Encrypted Media Extensions,” W3C, September 18, 2017, https://www.w3.org/TR/encrypted-media/. ↩

- The introduction of the EFF resignation letter from the WWW Consortium states that W3C by enabling and standardizing Encrypted Media Extensions, cedes control from users to remote parties and provides a web browser version of the DRM. “World Wide Web Consortium abandons consensus, standardizes DRM with 58.4% support, EFF resigns,” BOINGBOING, September 9, 2017, https://boingboing.net/2017/09/18/antifeatures-for-all.html. ↩

- An illustrative example of the media lobbying in the formation of legal decisions is the PirateBay court case in the Netherlands, which sentenced the defendants in prison time and large monetary fines. The Dutch anti-piracy group Stichting Brein (BREIN) took the case to European Court of Justice, which ruled that Dutch ISPs can be forced to block access to The Pirate Bay (It is worth mentioning here that the peer-2-peer website is not any more run by their founding members nor does it carry on with their original project of sharing. It has instead become commercial, displaying many advertisements). Relative source: “Unexpected Court Ruling Could Destroy the Pirate Bay,” Digital Music News, June 14, 2017, https://www.digitalmusicnews.com/2017/06/14/the-pirate-bay-european-ban/. ↩

- “Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor,” Wikipedia, last modified April 6, 2018, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frederick_II,_Holy_Roman_Emperor. ↩

- Corneilia Vismann, Files: Law and Media Technology, trans. Geoffrey Winthrop-Young (California, Stanford University Press, 2008), 84. ↩

- “Qualifing for Content ID,” YouTube, Google Support,: accessed February 2, 2017, https://support.google.com/youtube/answer/1311402?hl=en&ref_topic=2778544. ↩

- “Youtube Help Copyright,” YouTube, Google Support, accessed February 2, 2017, https://support.google.com/youtube/answer/1311402. ↩

- “Content Verification Program,” YouTube, accessed February 2, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/cvp_app. ↩

- Preview of the copyright registration web form, a 22 page document available to download from https://www.copyright.gov/registration/docs/pa-standard.pptx. “Motion Pictures copyright claims,” United States Copyright Office, accessed February 2, 2017, https://www.copyright.gov/registration/motion-pictures/index.html. ↩

- YouTube web-page about account termination upon three copyright strikes informs: If you receive three copyright strikes: 1. Your account, along with any associated channels, is subject to termination. 2. All the videos uploaded to your account will be removed. 3. You won’t be able to create new channels. Google Support, “Copyright strike basics,” https://support.google.com/youtube/answer/2814000. ↩

- YouTube web-page on how to resolve a copyright strike: There are three ways to resolve a copyright strike: 1. Wait for it to expire: Copyright strikes expire after 90 days, as long as you complete Copyright School. 2. Get a retraction: You can contact the person who claimed your video and ask them to retract their claim of copyright infringement. 3. Submit a counter notification: If your video was mistakenly removed because it was misidentified as infringing, or qualifies as a potential fair use, you may wish to submit a counter notification. Google Support, “Copyright strike basics,” https://support.google.com/youtube/answer/2814000. ↩

- “Copyright School,” YouTube, (one must sign-in to visit the page,) accessed April 2, 2018, http://www.youtube.com/copyright_school. ↩

- Google Support, “Youtube Content ID eligibility.” ↩

- YouTube provides a mandatory video about copyright infringement plus a quiz for those users who received a copyright infringement notification, or for those who wish to restore their terminated accounts due to them violating copyright for three times. A summary about the video and the quiz is discussed in “YouTube Copyright School,” Mashable, April 14, 2011, http://mashable.com/2011/04/14/youtube-copyright-school/#x07jtec3GaqP. ↩

- “Law and Guidance,” United States Copyright Office, accessed April 2, 2018, https://www.copyright.gov/. ↩

- “Performing Arts,” United States Copyright Office, accessed April 2, 2018, https://www.copyright.gov/registration/performing-arts/index.html. ↩

- “Subject matter of copyright: National origin,” Copyright Act, 17 US. Code § 104, accessed April 2, 2018, https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/17/104. “Berne Convention: Applicability,” Wikipedia, last modified April 19, 2018, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Berne_Convention#Applicability. ↩

- Moberg v. 33T LLC (2009), accessed March 28, 2017, https://cases.justia.com/federal/district-courts/delaware/dedce/1:2008cv00625/41082/24/0.pdf?ts=1377116699. ↩

- Chris Dombkowski, “Simultaneous Internet Publication and the Berne Convention,” Santa Clara Technology Law Journal, vol. 29, no. 4 (2012), http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/chtlj/vol29/iss4/3. ↩

- “Forms,” United States Copyright Office, accessed April 2, 2018, https://www.copyright.gov/forms/. ↩

- In their contact web page, only the Press department link provides a contact email for YouTube, other requests should be sent by snail mail, accessed April 18, 2018, https://www.youtube.com/t/contact_us. ↩

- “Terms of Service,” YouTube, accessed April 2, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/t/terms. ↩

- “YouTube partner’s earnings overview,” YouTube, Google Support, https://support.google.com/youtube/answer/72902?hl=en. ↩

- Wikipedia, “Berne Convention.” ↩

- Vismann, Files. ↩

- Vismann, Files, 72. ↩

- Diplomatics (in American English, and in most anglophone countries), or diplomatic (in British English), is a scholar discipline centered on the critical analysis of documents (especially, historical documents). See “Diplomatics,” Wikipedia, last modified December 19, 2017, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diplomatics. ↩

- Vismann, Files, 75. ↩

- In the first volume of The Archiv for Urkundenforschung (Archive for document research) in 1908, by Harry Breslau, Michael Tangl, and Karl Brandi, explain that archival documents and files, which were neglected until then, started to be included in historians and librarians’ research methods (Vismann, Files, 75). Digitalized copy of the German book available at Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/archivfrurkunde00unkngoog. ↩

- Stephanie Lysyk, “Love of the Censor: Legendre, Censorship, and the Theater of the Basoche”, Law and Literature, vol. 11, no. 2 (2014):113-133 https://doi.org/10.1080/1535685X.1999.11015592. ↩

- See for example the Japanese manga Mai Mai Miracle, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HmSY8idi528 or the 1960s movie Inherit the Wind, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e06lmx5uiZU. ↩

- Video with geometric shapes not monetized: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nCNmjL1DbcM. Monetized Video collage with the untouched extensive footage from Harry Potter (YouTube’s updated Terms of Service from April 6, 2017 introduced a threshold of 10.000 views in order to allow ads display, thus the monetized version of the remix experiment has no more ads to display): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PmmvkLfRLBI. ↩

- About YouTube monetizing threshold see Ben Popper, “YouTube will no longer allow creators to make money until they reach 10,000 views,” The Verge, April 6, 2017, https://www.theverge.com/2017/4/6/15209220/youtube-partner-program-rule-change-monetize-ads-10000-views, and “Introducing Expanded YouTube Partner Program Safeguards to Protect Creators,” Creator Blog, Google, April 6, 2017, https://youtube-creators.googleblog.com/2017/04/introducing-expanded-youtube-partner.html . ↩

- Governments have frequently in the past resorted to the services of entrepreneurial financiers (farmers) to whom they lease the right to collect the whole of the tax revenue due to the state in return for the farmers’ fixed instalments of payment into the treasury. See “Farm (revenue leasing),” Wikipedia, last modified January 31, 2018, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Farm_(revenue_leasing). ↩

- Andrew Zega and Bernd H. Dams, “Ledoux & the All-Seeing Eye,” Architectural Watercolors, March 13, 2012, http://architecturalwatercolors.blogspot.gr/2012/03/ledoux-all-seeing-eye.html. ↩

- Wikipedia, “Ferme Generale.” ↩

- ExtraCity, Antwerp, Belgium, www.extracity.org ↩

- “Our Story,” New America, https://www.newamerica.org/our-story/. ↩

- On June 27, 2017, Google was fined $2.7 billion by European antitrust authorities for favouring their own services over those of smaller competitors. See campaign “Citizens Against Monopoly,” Open Markets, accessed on September 13, 201,7 https://citizensagainstmonopoly.org/google-dont-be-evil/. ↩

- Ippolita, The Dark Side of Google, 48-50. ↩

- Google Cultural Institute in France, accessed September 15, 2017, https://www.google.com/culturalinstitute/thelab/. ↩

- Google Digital Garage, accessed September 15, 2017, https://learndigital.withgoogle.com/digitalgarage/. ↩

- Benjamin H. Bratton, The Stack: On Software and Sovereignty (Massachusetts: MIT press, 2015), 295. ↩

- For example, at the moment of writing this paper, the city of Munich, in Germany, considered a move to Windows from Linux and in the longer term to move all digital infrastructure to cloud computing. See Nick Heath, “End of an open source era,” TechRepublic, November 23, 2017, https://www.techrepublic.com/article/end-of-an-open-source-era-linux-pioneer-munich-confirms-switch-to-windows-10/. ↩

- Bratton, The Stack, 110-111. ↩

- Bratton, 114. ↩

- Bratton, 115. ↩

- Amy J. Cohen, “Dispute Systems Design: Neoliberalism, and the Problem of Scale,” Harvard Negotiation Law Review, 14 (Winter 2009), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1448806. ↩

- Cohen, “Dispute Systems Design,” 53. ↩

- Cohen, “Dispute Systems Design,” 65-66, 70. ↩

- Cohen, “Dispute Systems Design,” 73-74. ↩

- Cohen comments on Reagan Administration by referring to Ian Ayres & John Braithwaite, Responsive Regulation:Transcending Deregulation Debate (1992). The authors’ review of Reagan’s policies led them to characterize our era as one in which ‘dramatic regulatory, deregulatory, and re-regulatory shifts are occurring simultaneously’. See Cohen, “Dispute Systems Design,” 59. ↩

- An example of value redistribution as a dispute resolution remedy, which renders social collective ends vulnerable, is the case of Unocal Corporation and residents of a California community. In the wake of a chemical spill, residents traded their request to control Unocal’s annual environmental audits for their community’s projects funding. See Cohen, “Neoliberalism,” 73-74. ↩

- Cohen, “Dispute Systems Design,” 75-80. ↩

- Vismann, Files, 104. ↩

- At the time of the writing, the European Commission was still working on the draft proposal, which leaked to some media outlets. However, as of March 2019, the new copyright proposal has been officially presented in the European parliament and awaits for voting approval. “A final version resulting from negotiations during Trilogue discussions was presented to the European Parliament on 13 February 2019. If approved in Parliament between March 25th and 28th 2019, each of the EU’s member countries would then be required to enact laws within 24 months to support the Directive.”, retrieved from Wikipedia on March 11, 2019, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Directive_on_Copyright_in_the_Digital_Single_Market. ↩

- Sam Shead and Reuters, “Europe’s leaders demand that US internet giants remove extremist content within 2 hours,” Business Insider, September 20, 2017, http://www.businessinsider.com/r-at-un-britain-to-push-internet-firms-to-remove-extremist-content-quicker-2017-9. ↩