Introduction

The original Spanish title of Arturo Escobar’s Designs for the Pluriverse 1 uses the term disoñar to allude to “dreaming-designing” – a multitude of different ways through which humans think about the future, anticipate what will come, imagine alternatives, and construct new possibilities 2. In this paper, we describe two very different design investigations. Each responds in different ways to the challenges and opportunities of machine learning artificial intelligence (AI) technologies.

The common theme between our two investigations is their central reliance on the mathematical methods of Bayesian probability 3, which allows computation when knowledge, or degrees of belief, have been expressed numerically 4. All machine learning methods involve numerical encoding of past observations, in order to predict future events. In famous AI systems like ChatGPT, the past observations are the text the system is trained on, while the predicted future is a sequence of words most likely to follow a prompt 5. Our own investigation is far simpler than such massive systems. It uses Bayesian probability simply to describe the likelihood of one event given another, with further observations or events combined into a Bayesian network of possible causes and effects 6.

In our previous work in collaboration with teachers and curriculum designers, we have created educational tools that we hope will help equip young people in Africa to be empowered as developers and users of AI through early understanding of Bayesian probability. Projects such as ScratchTuring 7 provide the facilities of Probabilistic Programming Languages (PPLs), 8 – tools for describing Bayesian networks – using teaching examples from African settings. In this paper, we juxtapose the educational research underpinning those tools with the design of domain-specific PPLs that can be used to model more complex scenarios.

To enumerate the Bayesian ways of “dreaming-designing” that we are concerned with, these include: mathematical methods that can be used to speak of the future; anticipating the future of AI technologies that use those methods; equipping diverse people and populations with access to those methods; and imagining new computational tools that speak to the needs and customs of diverse potential users.

In the rest of this paper, we bring together disparate research approaches in ways that could seem jarring, through the collision of traditional knowledge with cutting-edge research into machine learning AI tools. As with Escobar’s “dreaming-designing,” there is no simple coherence between registers that may appear anthropological on one hand, or technological on the other. In this project we offer the encounter as a design exercise in the spirit of critical technical practice 9, presenting our tools and our observations with an invitation for the reader to take these as pluriversal perspectives on Bayesian knowledge.

The structure of the paper is as follows. First, we describe the context of our collaboration with Ju/’hoansi, including the educational agenda motivating that work. We then present findings from our investigation of the ways that Ju/’hoansi speak about the future, ways of knowing, and making decisions in the presence of uncertainty. The subject matter and scope of this investigation was initially motivated by our educational and technical interest in Bayesian methods, influenced by the work of David MacKay 10, but giving priority to the life experience and ways of talking about experiences of Ju/’hoansi. Our presentation then makes an abrupt but intentional turn, describing a recent software development project undertaken within the conventional Western framing of AI research. This project, whose objective was to make Bayesian modelling more accessible to non-specialists via a domain-specific PPL, was similarly motivated by the work of MacKay 11 and Pearl 12. Finally, we turn again to critique the functionality and intentions of this (wholly Western) tool from the perspective of our Ju/’hoansi collaborators.

Prior work

Although this juxtaposition of the computational and ethnographic may seem jarring, we note that we are not the first to bring together these perspectives, even though we may be the first to present both sides of the account in a single journal publication about the role of software in contemporary life. In particular, we build on the work of David Spiegelhalter, who applied Judea Pearl’s early research when designing BUGS, the first PPL 13. Spiegelhalter and MacKay both taught at the African Institute for Mathematical Sciences (AIMS), and one outcome of Spiegelhalter’s time at AIMS was the short book on teaching probability that we used to design our own lesson material 14. As well as benefiting from the insights of these pioneers, our work is also influenced by Helen Verran whose fieldwork on number systems in Nigeria, as Emmanuel Ofuasia 15 explains, distinctly recognises African mathematics, albeit not consistently in the terms of its own intrinsic logic 16.

Our investigation of Ju/’hoansi ways of describing uncertainty, and potentially quantifying degrees of certainty in Bayesian terms, can also be compared to previous projects sometimes described as ethnomathematics 17. The field of anthropology pays close attention to ways of constructing and representing knowledge about the world, and some of these can be compared to or contrasted with Western mathematical practices 18. Among computer scientists, one particularly celebrated body of work is that of Ron Eglash and his Culturally Situated Design Tools team, whose ethnocomputing agenda 19 does draw on African design among other forms of traditional knowledge 20, and uses these elements of other knowledge systems as the basis for a more inclusive STEM teaching curriculum 21. While celebrating this work, our own project looks specifically at probabilistic reasoning. African theorists increasingly relate traditional knowledge systems to probability and AI; describing, for instance, how the Ifá system of divination contains all the features of AI 22 and may offer a decolonising route 23. Reasoning about likelihood and belief is not only fundamental to culturally-specific ways of knowing in different languages and traditions, but is also (in its Bayesian formulation) fundamental to recent developments in AI. Recent developments in the AI derived from Western knowledge systems, however, seem poised to have great significance for many traditional communities around the world, such as the Ju/’hoansi. Although our ethnographic enquiries are not intended instrumentally to elicit design requirements 24, the juxtaposition of AI tool design with Ju/’hoansi perspectives offers an alternative standpoint for critical technical practice 25.

Pluriversal perspectives through narrative: Storytelling for the Ju|’hoansi

Reasoning about and preparing for the future is a serious concern in all societies, and oral storytelling figures in the many ways it is negotiated. Storytelling has been a vital bridge between perspectives about prediction and likelihood in our work with Ju/’hoansi people in the Nyae Nyae conservancy of northeastern Namibia’s remote Kalahari 26. In Namibia, the Ju/’hoan are the largest language group of the San, whose traditional nomadic life-style became popularised by anthropology’s “myth of the Bushmen” 27. Today, some 1,600 Ju/’hoansi people live in some 40 small permanent villages, or Noresi, scattered across the 8,992km2 bush and another 1,400 live most of the time in the town of Tsumkwe 28. The Ju/’hoan established the Nyae Nyae conservancy, Namibia’s first communal conservation scheme 29 that, with the Ju/’hoan Traditional Authority and Nyae Nyae Community Forest, was a basis for seeking to clarify rights and settle disputes over land 30, and exploit the cultural economics of indigeneity for their livelihood in the ‘modern world’ 31. Nonetheless, like other San groups, the Ju/’hoan are culturally marginalized and have limited political representation 32.

Oral storytelling has long been promoted in recentering indigenous peoples’ knowledges 33, and can challenge the different ways that technology performs in epistemic violence and injustice 34 to undervalue, exclude, silence, misrepresent or systematically distort people’s meanings, contributions and communicative practices. Recent discussions note storytelling’s role in participatory approaches to address power relations 35, as an explicitly decolonial alternative to neoliberal epistemes that maintain certain institutions as centres of knowledge production 36, and as radically inclusive story-telling codesign process to address the ‘always situated-ness’ of technology designers and the ever present threat of design collapsing into neo-colonialism 37. In the field of human-computer interaction (HCI), oral storytelling has helped in situating technology design in Africa. It has, for instance, addressed the need to prioritise voice, over visual images 38; enabled elders and other community members to engage in a griot-style methodology 39; and inspired new interactions to support qualities of collective sense-making that fuse meaning, sound, body movement, and rhythm 40 and respond to the temporalities that software development embeds 41. HCI analysis has also shown the importance of refraining from privileging non-local paradigms in interpreting stories in rural Africa 42 and thereby contributing to epistemic injustice 43. Indeed, stories provide meaning-making within cultural contexts, providing data from the insiders (emic) perspective, rather than (etic) external explanations of observer-oriented data 44 and offer a counter to the deficit narratives in data science in Africa 45 that emphasise a lack of education and technological resources rather than indigenous meanings, concepts and practices.

The Ju|’hoansi San are considered “the most fully described indigenous people in all of anthropology” 46 and there are many analyses of their storytelling and stories, be that from how people tell stories in response to a question 47 to the ways stories about people and animals function to enable survival. Early anthropological accounts are replete with stories about people’s anxieties about lack of food, where game was found and who killed it, and who shared or did not share food, which appreciated characteristics such as generosity, industriousness, frugality, and humility and scorned stinginess, laziness, prodigality, and arrogance 48. More contemporary accounts describe how stories told by evening firelight sooth tensions 49 and those created during hunts shape the trajectory of tracking. Expert Ju|’hoansi trackers observe signs and create causal connections between them to predict game movements and speculate to explain signs that are unclear or otherwise meaningless 50. They gather every piece of relevant information, from natural signs (e.g. spoor) to cultural symbols, (e.g. jinxes and myths) to enable “noticing” or “good sense” 51. When new information emerges that contradicts expectations, trackers construct auxiliary hypotheses to explain tracks 52. Adjusting stories according to observations is analogous to adjusting the likelihood of a prior and creating new priors as observations accrue in Bayesian inference and imagination increases opportunities to locate game and learn more about animal behaviours. This imagining includes trackers identifying themselves with the animal to anticipate its route, drawing on traditions that consider that animals were formerly people and have human characteristics. Indeed, while stories might depict cause-and-effect representations of environments, strategies and outcomes, Ju/hoansi do not always interpret them as imagined courses of action. For instance, folktales prepare people to adapt to unexpected change 53. Ju/hoansi folktales deal with everyday challenges, such as weather, procuring game, carnivore attacks, and relations with in-laws 54, and evoke emotional responses that promote recalibrating the relative value and significance of things 55. Indeed, causality is inconsistent with the way folktales, and other Ju/hoansi rituals, emphasize transformation and experiencing the world as ongoing change 56. Their narrativity gives presence inside a changing stream of events 57, often marked by inconsistencies, vagueness and shape-shifting (for instance a person becoming a lion, an eland turning into rain) and their meanings and narratives are not standardized or fixed across tellers.

Stories change not only because of their tellers’ personal differences but because the surprise of alterations vitalises. While also for entertainment, fun and enjoyment, storytelling aims to elicit feelings of transformation. Keeney and Keeney 58 suggest that telling folktales awakens and transmits “n/om”, a spiritual energy that is responsible for a story’s liveliness and connection with audience, which invigorates the context in which the story is told; and warn that using media to retain a story’s form can destroy “n/om”. Thus, many endeavours in the past 25-years recognize the role of folktales and storytelling in preserving Ju/’hoan knowledge and culture. For instance, both the Ju/’hoan Transcription Group (JTG), established in 2002 to document Ju/’hoan language 59, and the Nyae Nyae Village Schools project recognize the role of stories in epistemic justice for the Ju|’hoansi 60; and, more inhabitants have been encouraged to recognize the value of intergenerational storytelling, to remind the youngsters so they can keep what was there in the past.

Collaboration in the Nyae Nyae

Storytelling contributed to participants’ excitement in playing a game that we created to explore computational and educational bridges between Ju|’hoan people’s predictive reasoning and AI systems. Nic has engaged with San groups and the San Council of Namibia in different technology projects for over 10 years. She was introduced to Ju|’hoan people, in 2016, by Candi Miller who established links 25 years ago and co-founded the Nyae Nyae Village Schools Feeding project 61. Ju|’hoansi interest in storytelling has contributed to our technology projects together. For instance, from 2019 we piloted a community-based system to enable people to share stories and news between villages across the conservancy despite the absence of electricity and mobile access, described in short film created by Ju|’hoan people: https://videos.apc.org/u/apc/m/talking-around-elephants-sb/.

In early 2020 we began a new collaboration to explore how to enable Ju|’hoan people to participate in the future design and use of AI 62. Our collaborations were co-located for six weeks, during the non-local researchers’ visits to the Nyae Nyae in 2020 and 2022, and remote by email and WhatsApp for the rest of the time. Approximately 50, mostly Ju/’hoansi people in the Nyae Nyae have participated in discussions, interviews and other activities which involved Nic, Alan and Helen Arnold (a maths teacher also visiting from Cambridge) or the Ju/’hoansi collaborators on their own. Participants included educators and learners in Tsumkwe high school and the village schools, staff at the Conservancy and tribal authority offices and many other inhabitants of Tsumkwe and different villages. Our conversations and interviews discussed mathematics curricula, everyday scenarios in which people make predictions and decisions, and particular topics such as predicting the weather. We also played games of chance using spinner games and discussed perspectives on the games.

We planned research in cycles that discussed activities, to generate insights, and then reflected on the activities and insights. This included introducing the Ju/’hoansi collaborators to Western mathematical concepts, particularly in relation to Bayesian and frequentist statistics, and sets of open-ended questions to prompt them to express their views about activities and check on the interpretations of non-Ju/’hoansi collaborators. We video-recorded all activities involving non-Ju/’hoansi collaborators and usually obtained a written transcript by an expert Ju/’hoan-to-English language translator. When Ju/’hoansi collaborators undertook activities on their own they typed brief summaries, in English, and/or verbally explained their insights in English, which we video recorded and transcribed for them.

Our analysis is grounded in the research activities, as insights and reflection on one set of activities prompted the next activity, and summatively by grouping themes to prepare articles for publication. To prepare articles Nic arranged themes, often comprised of extracts from transcripts or email communications between collaborators, into draft narratives sent by email and WhatsApp to Ju/’hoansi collaborators. Since technical terminology is new to the Ju/’hoansi collaborators, the non- Ju/’hoansi collaborators wrote shorter common word summaries, using the same headings in draft articles.

Communicating about likelihood: spinners and stories

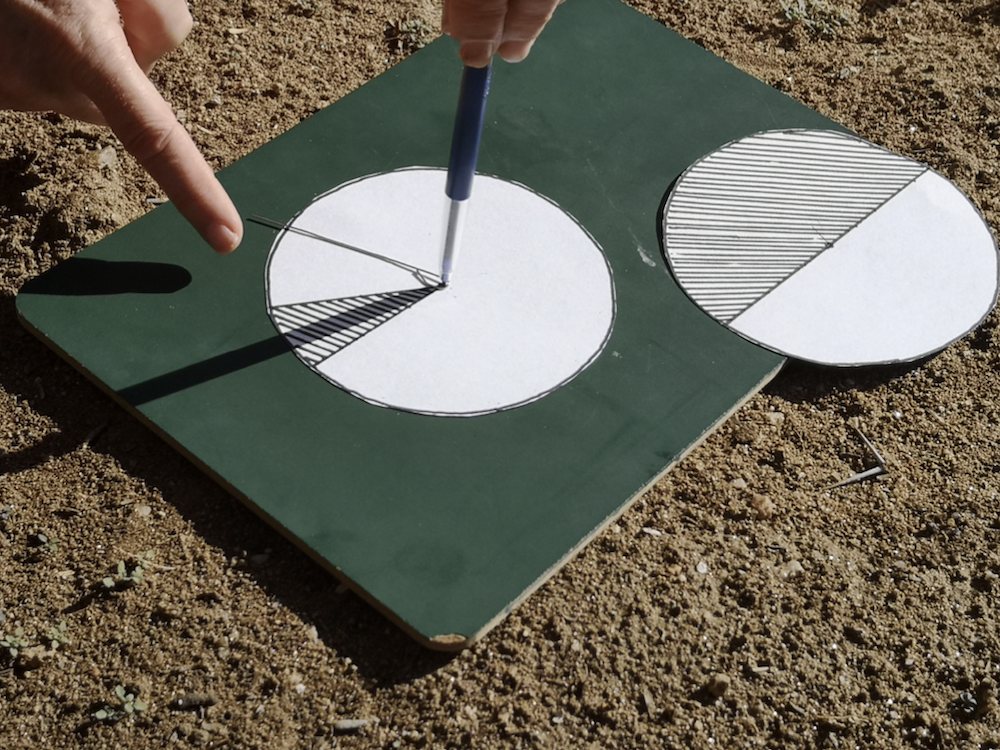

To support discussions about likelihood and prediction we developed games of chance using spinners, inspired by Gage and Spiegelhalter’s 63 teaching aids that integrate Bayesian approaches into a traditional curriculum for statistics. We made the spinners from paper when in the Nyae Nyae and digitally online when we were not 64. A paper spinner comprised a circle anchored in the centre with an unfolded paperclip and which, when flicked, may or may not stop in a coloured sector of the circle (Fig. 1). Making spinners with different sized coloured sectors to represent the likelihoods of different events provided a basis for discussing probability. This included, for instance, explaining the difference between Frequentist and Bayesian approaches to probability and considering the frequencies of events, how outcomes can modify future expectations and reasoning about relationships between events and conditional probabilities. Different groups of mostly younger Ju/’hoansi people made and played spinner games. We discussed the sizes of the spinner sectors as a way to quantitatively represent the likelihood and conditionality of events in Ju/’hoansi’ stories about everyday life.

Participants’ stories about events and decisions that spinners could represent and their engagement in games through storytelling provided rich insights into concepts related to prediction, certainty and risk. Relating spinners to these stories also helped to open up discussions about predictive reasoning and AI systems. However, participants’ comments and our collaborative reflection, also revealed that a non-Ju/’hoansi framing, such as about causality, might have influenced the direction of dialogue and interpretation around spinners. Thus, we focused analysis on stories that might show some of the concepts encountered in the spinner games. Throughout our research Charlie recounted short stories from his own life, additionally we prompted him for stories of his own and told by other Ju|’hoan people to illustrate particular concepts. Prompts included stories about events that were “surprising”, “expected” and “good luck” and about “taking a risk” and “predicting when a prediction was correct”. We discussed stories extensively, much as Ju|’hoan people do together in reflecting on what they learned from a story and considered their turn of phrase in the translation drawing on Charlie’s extensive experience in The Ju/’hoan Transcription Group (JTG).

Storytelling

We distinguish storytelling from conversing based on Ju/’hoansi definitions. Storytelling tends to emphasise that a person tells a story from the beginning to the end while others listen, while in conversation different people add facts along the way. In storytelling, people only contribute to the story if they have experienced what it touches upon or disagree with the way it is told, and then may start debating facts or points that the storyteller has made, until they reach agreement. The stories we recount in this article are about everyday life or serious happenings in the past that teach Ju/’hoansi people about real life. They are not considered folktales or about imagining something that may happen in future. Thus, many stories told in our research are about events in the past few months or a situation that has repeated over and again, and conveyed to bring a sense of reality. When Ju/’hoansi participants reflected on storytelling, they referred to both the emotional experience of stories and to relationships between the way that events unfold and people’s orientation towards the world. We present our findings to reflect the themes contained in these stories: how the different chances and risks people encounter are contingent on their position in an unequal world; how complex conditions arise in interaction with humans and animals; and the role of hope in managing uncertainty.

Chance and risks when moving through the world unequally

Stories illustrate how inequalities shape the probabilities of events and the risks they pose as people move through worlds, whether on foot or in a motor vehicle. From the start of explaining our project to inhabitants, probability repeatedly related to Ju/’hoansi people’s getting a “hike”, or a ride in a vehicle along the 280km road between Grootfontein and Tsumkwe. When we parked our large, comfortable off-road vehicle near a village, 30km from Tsumkwe, a group standing on the road asked for a ride to Tsumkwe. We explained our discussion in their village might take 1.5 hours and they deliberated about whether to accompany us to the village or wait on the road for the chance of another car passing and giving them a ride in the next 30-minutes. Thus, when introducing the concept of probability, and the spinner game, in the village Charlie referred to how many cars pass near the village, stop, have space and would give rides.

Different groups identified various factors that affect the probability of getting hikes when we discussed creating spinner games. For instance, both Ju|’hoan collaborators chose spinners with large sectors to represent a high chance of a hike on a day at month’s end, which is when many workers are paid, more vehicles pass and passengers can pay transport levies. Both said it is not easy to get hikes on other days, a person will get a lift if “lucky”, and one chose a spinner with a 50/50 chance and the other with a very slim coloured sector. They said that learners, who board at the secondary school, would understand probability by linking spinners to stories about the best day of the week to get a hike back to school after going home to their village. When they made spinner games about getting a hike to a soccer match, young people noted that Saturday offered less chances of transport, because people travel from Tsumkwe on Fridays to their homes in villages and return on Sundays for work. They also said the type of vehicle affected whether a driver would offer a hike; for instance, compared with a lorry or backy (pick-up), sedan cars have less capacity and their drivers are less interested in soccer matches. People’s position in moving through the world, however, also shapes the probability of events. Charlie explained applying a Bayesian approach to predicting travelling to Grootfontein on any other day than month-end. He began his prediction at a 50:50 chance on Monday morning, which he adjusted to 1 in 4 at the end of the day, because he saw a car but there was no room for him; he saw two cars on Tuesday but the driver refused to take him because he didn’t have money to pay for the ride and so he kept the kept the probability to 1 in 4; on Wednesday he saw no cars going to Grootfontein so lowered the probability to 0/4. However, on Thursday he got a lift so raised it to 1/4.

Obviously, experience also shapes preparing for the probability of events. For instance, unless he is too sick to walk, or is able to get a lift to attend a meeting, Charlie usually walks to Tsumkwe on Sunday afternoons to do his translation work and then back to his village on Wednesday at noon. His choice of the time to start his journey reflects past encounters with elephants, as he wrote in response to a prompt for a story about a surprising situation:

… So, one morning I walked early about six o’clock so I could get back at the village before sunset. On my way a huge elephant suddenly walked into the road from the side right in front of me. When I saw the elephant I was so shocked that I could just freeze on my steps. To my surprise the elephant just looked at me from the corner of one eye, trumpeted and ran off across the road. I thought to go back before I was probably going to get a dangerous one but encouraged myself to keep moving without any sign of elephant until I safely reached Tsumkwe. From that day I decide to never walk in the early but rather walk at about noon while the animals are not roaming but are taking shelter from the sun under tree shades.

The events in “I met eye to an eye with an elephant” had happened a few months before, but are not unusual during a drought. Along with past experience, people’s specific, and unequal, positions affect how perceive and respond to the risks. Consider, for instance, a story about a risky situation told by a man in his fifties with poor eyesight:

I was walking with my wife to the village from Tsumkwe knowing that we were likely to encounter with an elephant or elephants on our way, because it was a dry season, and the giants were move back and forth across the road to find water and feeding. After a while of walking my wife saw something dark far in the road ahead and told me that she saw something far ahead, but I could (not) see because of my poor eyesight. As we came nearer, we saw that it was an elephant. So, when the elephant saw us, it went off the road and stood behind the bushes. I told my wife that we make take a detour around the elephant to proceed our journey trying to do that, a few meters away from us the elephant trumpeted and charged on us, so we ran wildly for our safety. My wife ran me out, because she was younger, and I neither was wearing proper shoes. So, I fell down and started shouting, my wife and screaming and, to our luck, the elephant stopped and take another way, because elephants do not like noise.

As summarised by Charlie, these stories show how Ju/’hoansi talk about the future. Especially when people must make a decision based on their experience and this decision will explain how the future will be, as a result of the decision-making, compared with the current situation. We relate this to the focus in Bayesian probability on being aware of prior expectation in assessing likelihoods and the role of evidence in updating beliefs on the basis of experience.

Humans and other animals contribute complex conditions

We realised that associating spinners with stories involving interactions between humans, such as rides in vehicles, or between humans and animals had more complex conditionality. Ju|’hoan collaborators asserted that elephants and all other animals must be understood as a potential, not confirmed, danger as their behaviour is unpredictable and they do not always cause harm. Different factors cause an elephant to be dangerous, including sickness, injury, being chased from their herd, or seeing something suspicious they were not expecting, and animals respond to humans in different ways. When drinking at a water hole or browsing on bushes, an elephant will smell a person or other creature that approaches too closely, watch and then may charge or run away. People also respond in different ways; for instance, Charlie’s elders had explained that elephants don’t like noise, so he started beating on metal to scare away three elephants had come to his house and they ran away.

The topic of our first spinner game was based on inhabitants’ views of important lessons about daily life for children. A village group deliberated about learning about animal spoor and gathering food and settled on safely finding water in a tree. Their account informed a game with three spinners: one spinner represented whether or not there was a hole in a tree, another whether or not the hole contained water and third whether or not that hole contained a snake. Other people in the Nyae Nyae were familiar with finding water in a tree and agreed about the importance of learning the risks associated with wild animals, such as the probabilities of being bitten close to a tree where people usually see a snake, or an attack if a child entered a lion’s hide. However, when people played the tree-water-snake game they said the probability we had configured in our spinners were not plausible and depended on the number of trees in the area and whether someone had first dropped a stone in the hole to avoid a snake. Thus, Charlie reflected that this story might become too long for younger children to learn.

Another group suggested a spinner game about deciding on the direction in which to walk to gather bush food, influenced by how many animals were in different places. Charlie said this presented a simpler game for younger children, since it was only about decisions about where to go and availability of food. The first spinner selects north or south, and the second is about the certainty and uncertainty of finding bush food in the north or south. Charlie proposed that children could adapt the game to their knowledge of the environment and past, present climate conditions, and suggested a story to contextualise this:

Once upon a time there was some kind of famine. It was very hard and we decided to go out gathering. It was a poor rainy season and so, there were rarely bush food as the wild animals have nearly depleted all fruit bearing and underground bush food…. We found only a few raisin-bush berries that were also dried out by the scorching sun and it was so tasteless and we were very thirsty and hungry out in the bush. That was the hardest day we ever experienced out in the bush. So, we had to come back and sleep with the empty tummies. From that day we decided to move away from that place to find a better place where we could have veldt food and where there are also waterholes nearby.

Hope and preparation

Against the challenges of life in the Kalahari, a common narrative shows the need to inspire hope. Charlie said that over the years his dad and other elders often told stories about fortunate happenings during famines, such as:

Very long ago there was some kind of famine in our village. It was a very dry season and all the bush food were depleted. There was almost nothing that we could eat except the gemsbok beans that we could survive on and they were also hard to find as the veld fires also destroyed big parts of the nature. One good morning I woke up with hope that something good was going to happen that day. So, I decided to take a walk into the bush. So, I called my dog and set off to the bush. After a while of walk I saw some footprints of wild dogs chasing after a kudu. Without hesitating I decide to track it down. Not far away I saw two male wild dogs just starting to feed on a kudu carcass. I urged the dog on to them and the dog started to bark, and the wild dogs ran off, because these are harmless predators. I was very delighted that we were going to have meat today. After then I took my jacket off, pick two sticks and made a cross then I put my jacket over it so it could look like a man to frighten the wild dogs away if they would come back to the carcass. So, I went start to walk back to the village and came across a tree where I saw honeybees going in and out. Now we have meet and we have honey as well I said to myself quietly. Back at the village I told the people about my luck of finding meet and honey at the same time. We quickly wrapped up what we could take along and set off to the spot, cut up the carcass and back and collected the honey as well. Reaching the village in the evening my father arrived back from the bush who was also out hunting. He had shot and killed a giraffe and told us the good news. The next morning, we would go and get more meat from the giraffe and the village would have plenty of meat now. No more worries about what to eat the next day. That was really a day of good luck.

This story has many instances of good luck. It’s unusual to come upon a kudu’s carcass, which would be eaten by other animals if humans aren’t around. It’s also rare to walk near, and easily see, a honey hive and, usually, people must search for hives by walking, looking for the bees going in and out of holes in trees and carefully knocking on trees to see if there is any honey left after the larvae have grown.

People don’t go foraging only when they “wake up with hope that something good will happen” and may doubt they will get any food but go to see if they will be lucky. However, often they try to believe in a positive outcome, like telling themselves that something see in the distance is a tree not an elephant. For instance, Charlie recounted a story, told to him by a man in response to the prompt of something expected happening, that illustrates choosing to ignore negative signs:

A boy walked down the street expecting to meet his friend at the bar as they have agreed after he had made some calls and his friend couldn’t reply. Now came the second expectation of what he is going to see or hear. Arriving at the bar he saw a crowd of people surrounding a dead body covered with a dark piece of fabric. “What could this be?”, he started to ask himself from inside. As he was coming close, he realized that a few police officers and a police van were present. The next thing, he heard a police officer, probably the leader of the response group asking the crowd; “Who saw Kxao /Ui for the last time today”. He knew that something terrible might have happened his friend. So, in his thoughts he said; “I know that something has happened to my friend because of the numerous calls I made to him with no replies”. From there he just turned back home locked himself in his room sobbing. That night he could not have a single minute of sleeping. This was a sad expectation.

Sometimes people have a feeling or thought that something is likely to happen if they act in some way, even though they can’t really know exactly what the happening will be. For instance, Charlie said that he had been beaten and badly injured, years ago in junior secondary school, when he agreed to go out with two friends despite feeling that something was going to happen to him. He concluded that others should not be forced if they don’t desire to do something.

Hope relates to a person’s dreams about something positive or negative happening, their faith that what they dreamt will happen, and their thoughts, which also play a major role in what will to happen. Dreams are mostly about something in the past that a person is still concerned about, even if it has gone from their mind. However, some dreams can foretell the future, aligned or opposite to what they suggest. For instance, in response to a prompt about a correct prediction a 42-year-old man told Charlie a story about imagining the start of a good life which became a reality.

Some time ago one morning I woke up and it was like sunset. Then in a sudden it was like early morning again. When I open my eyes, I saw people marching along. Then in my imagination I saw a woman carrying a crying baby on her arms. To myself I thought this could be a new beginning with very good life. In the morning told my people about my experience and told them that there will be a very good life for us ahead. So, with no surprise our place, Tsumkwe start to develop very rapidly. Some Ju/’hoansi people found good jobs, some of them start to build brick houses and some of them even bought cars. So life really became easy and more people well-off.

This story illustrates symbolism in talking about the future: people marching depicts a search for new developments and a woman carrying a crying baby depicts a new beginning. It also illustrates ambiguity in Ju/’hoansi’s talk about the future: the blurriness of imagery in dreams and imagination, of awaking and drifting back to sleep, and of time shifting and times’ indeterminacy.

Many stories in our work together conveyed the felt-experiences of events, and depicted how people relate hope and desire to their bodies in different ways, such as to the “heart” or a being “hungry” to act. Descriptions refer to being exhausted by waiting for hikes, feeling hopeless as the wait extends, glad to be at home after looking for a hike in vain for days, sleeping with empty tummies, or feeling shock when seeing an elephant so close. A listener engages, emotionally, with a frightening or thrilling story, feels the storyteller’s experience and their mind considers how they themselves would act. Thus, when the day comes that the listener finds themselves in a similar situation their thoughts roll back to what they heard before in thinking how to follow or avoid whatever is good or not. However, as Charlie explains, “we are not always be prepared by a story””:

… a man has been walking lonely with a little axe care waiting for any danger to defend himself against the danger but nothing happens, but when the person does not expect anything, he might be attacked and killed eventually.

Spinners as tools for thinking collaboratively

To introduce the spinner game, collaborators would say, in Ju/’hoansi, “Jabij-abi n|ang se koa/tca ka n!uan” or “spin to find out where/what you come up with” and explain that it is like finding answers or information before carrying out a plan. Finding the answer involves people discussing the factors that shape the probability of events arising in the stories associated with the spinners. When groups played and created stories about their spinner games, they normally discussed conditions, dependencies and plausibility. Indeed, across our explorations we had difficulties expressing priors mathematically by associating numbers with experiences and expectations of events.

When pushed, Ju/’hoansi people related numbers to probability, although it was slightly easier to phrase priors using temporality. For instance, people do not expect to get a hike in less than an hour and may have to wait up to three hours on a Wednesday, if an arrangement hasn’t been made; people might expect rain in an hour or a few hours, a day, or up to three days if the rain clouds sprout in January. However, Ju/’hoansi collaborators would always assert the unpredictability of events and qualify dependencies, such as the specific times when vehicles were moving, or how a wind can bring or blow away the rainy clouds. People related quantity to probability; for instance, collaborators said it’s less usual to shoot a giraffe nowadays than in the past, when the giraffe numbers were high, and killings of giraffe have decreased since people hunted with guns and horses. Nonetheless, it was difficult to phrase expectations by quantifying instances, such as how many times in a year people might find a dead kudu, and most comments about observed frequency were broad explanations about why events were unusual, such as explaining that a person would need to come straight to a kudu’s carcass before it was eaten by animals. Indeed, numbers convey meanings about specific conditions that shape the probability of events 65. For instance, the number of animals can identify a herd or indicate their mood and the number of people foraging together can influence which direction to walk to bring home enough food, have more eyes to look for threats and ensure dangerous animals feel outnumbered and run off.

It’s important to stress that we do not interpret any disinclination to associate numbers with probability as some kind of ethnomathematical propensity or educational deficit amongst Ju/’hoansi. Uncertainty characterises life in the Nyae Nyae and ambiguity, ambivalence, and contradiction that is a marked feature of Ju/’hoansi’s engagements with researchers and visitors 66. Rather, the spinner games and stories associated with them reveal that collaborative discussion seems to be more vital to integrating Bayesian probability for Ju/’hoansi than translating observations into mathematical constructs. For instance, people will debate the direction to walk and recognise people’s expertise in making a decision; they will decide to plant when they see signs of the first rain, but continue to debate how sure they are and conclude together that it is the right time only when the first rains start; and will convince a friend tired of waiting for a hike to try for another hour and agree to go back if they don’t get a hike after that. Indeed, Ju/’hoansi prioritise trying to resolve disputes by talking, even when consensus cannot be reached.

Ju/’hoansi may use tangible objects in collaborative decision-making. Collaborators gave examples of tossing a coin to see which side it lands in deciding who kicks-off in football matches and explained that a hunter will let a pinch of sand run through his fingers to determine the wind direction and speed, and the group will go in the direction the wind blows to be down-wind of the animals they are searching for and avoid problem animals that might attack or charge. Indeed, we considered whether the spinners might feature in discussing decisions during planning in ways similar to /Xusi or /xu, or Oracle discs, that Ju/’hoansi collaborators described as a kind of media made of Eland leather that their elders used to predict if happenings had occurred. People would throw the Oracle discs onto the ground, or a piece of sheeting, almost in the same way as dice and use them to determine whether a hunt was successful and where it took place, which way to go for hunting or foraging for the next few days, if families far away were well or if someone had died, or to find out whether something they were suspicious about had happened somewhere. One collaborator compared the discs to using radios or telephones to get remote information before people had moved to a modern lifestyle and while most of the ten people (aged 32 to 53 years) who he asked knew about the discs, only Charlie had seen them in use. In fact, these days the discs may be used only in one village in the Nyae Nyae, and only in times when people are hunting. Although the spinners differ in form and the way they roll, the spinners might remind or inform people about the roles of Oracle discs in deciding about hiking, animals or gathering and finding out about family members’ health in villages far away, even if they differ in telling the future in divinatory or prophetic ways. We might consider both spinners and Oracle discs as a media for epistemic justice that extend beyond awareness that Western mathematical tools and outsiders to the Nyae Nyae, such as authors Alan and Nic, translate local experience, knowledge and stories through non-local logics. We suggest that these media support modes for epistemic justice: listening, debating and orally creating temporary convergences across plurality and ambivalence in an always ambiguous and always uncertain world.

PPLs as a practical critical technology

Our story now leaves the Nyae Nyae for a brief diversion (as we ourselves were forced to leave by the Covid-19 pandemic). Here we take a radical disciplinary turn, considering a very different approach to epistemic justice. As discussed in the introduction to this paper, an overarching agenda in our work has been to explore the potential to more widely support Bayesian reasoning and modelling in future through the design of novel Probabilistic Programming Languages (PPLs). As mentioned, we have applied PPL principles to explore the teaching of Bayesian probability with interactive educational tools, in both Western schools, and schools in Africa. However, this work has extended beyond educational applications, to other domains in which machine learning technologies are being deployed.

A fundamental difference between PPLs, and the neural network architectures that have become the dominant approach to probabilistic machine learning methods, is that the structure of the learned model is only ever implicit in a neural network, whereas it is specified explicitly in a PPL. The marketing rhetoric of human-like AI used to promote machine learning technologies has attempted to claim an equivalence between inference and programming, speaking as though the AI system has programmed itself, through a process that cannot be directly controlled or inspected.

The failings of machine learning-based AI to support fair critique, discussion, negotiation and collaboration are often characterised as problems of “explanation” or “transparency”, “trust” or “accountability,” and whole academic communities are being established to document and criticise the consequences. Purely neural network-based architectures derive their behaviour directly from data, effectively turning evidence into law, denying the collaborative possibilities of discussing causes or debating alternatives. We argue that PPLs may offer an alternative approach to neural networks, allowing policies and explanations to be described explicitly, while still enabling large-scale statistical evidence.

In experiments adapting this PPL philosophy for use by end-users who do not have technical expertise in AI, Alan’s technical team created a prototype that they called the Multiverse Explorer 67. The name comes from a common trope in science fiction and fantasy (including the award-winning movie Everything Everywhere All At Once, dir. Scheinert and Kwan, 2022), where the idea of the “multiverse” is adopted from a cosmological interpretation of quantum physics, in which every potential outcome of a quantum event does occur, but in a different universe. The set of all universes – the multiverse – is constantly expanding, following a branching time course of quantum events.

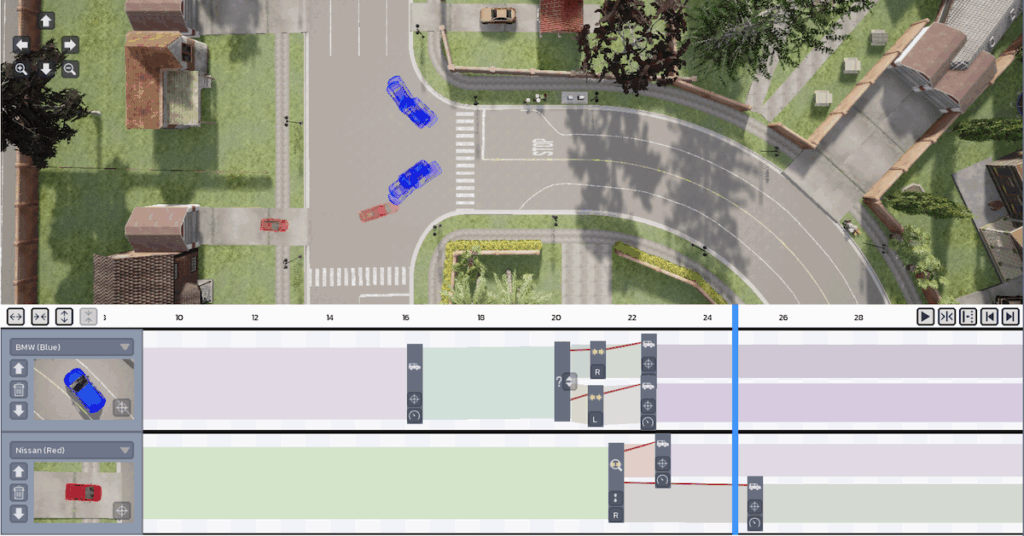

The Multiverse Explorer applies this fictional / philosophical metaphor to visualise the many outcomes of a probabilistic model, displaying a virtual reality rendering of a real scene (Fig. 2), in which possible alternative events appear as semi-transparent “ghosts.” Less probable outcomes are represented by more ghostly transparent objects. More probable events appear as relatively solid ghosts, while durable certainties of the world model form a solid background scene within which these ghostly possible futures can be observed interacting with each other.

Multiverse Explorer also reflects a kind of collaborative storytelling, despite the fact that it was created in a Western technological context that would not usually describe its narratives as “stories”. In a project funded by Boeing Corporation, the technical goal of the work had been to investigate future modes of decision making under uncertainty where humans would be able to work together with automated AI systems. Alan’s research team chose to illustrate this general problem in the domain of city driving, where the kinds of decision that must constantly be made by any car driver are familiar to Western audiences. This domain also allowed presentations of the work to make a contrast to the narratives of the “autonomous vehicle”, which very seldom pay attention to the problems of negotiation and collaboration that are essential to competent human driving, but almost entirely absent from the design of so-called autonomous vehicles 68.

The focus on a very specific kind of problem context is, at the time we write this, very unusual for PPL research. Programming language researchers more often describe the mathematical properties and capabilities of novel languages, rather than anticipate the kinds of application that might be created with them. Programming languages created for very specific kinds of application are often called “domain specific” languages. Multiverse Explorer, with its focus on decision making for autonomous vehicles, is thus one of the first examples of a domain specific PPL.

Inspecting the Multiverse Explorer from a pluriversal perspective

Multiverse Explorer has been described in greater detail for a technical computer science audience 69, but for this project we were interested to compare this example of a wholly Western approach to design for end-user applications to priorities and potential applications in the Kalahari. In this final section, we therefore juxtapose our experiments with PPLs for Western audiences with our investigation of Bayesian reasoning with Ju/’hoansi collaborators.

We prompted the Google Gemini large language model with the instruction: Please rewrite the following text in a form suitable for a mature adult who lives in a country that is not Western, educated, industrialised, rich or developed. Please use a simple vocabulary without specialist academic or scientific terminology, suitable for a person who is not fluent in written English. The rephrased version introduced terminology that had not been present in the technical paper, but helped Alan to recognise the underlying commonalities with our pluriversal perspective on storytelling, for example with the paraphrase “It’s like being able to make educated guesses about a story’s outcome,” in which he drew on work exploring narrative in AI that had also been supported by Boeing Corporation in parallel with the Multiverse project 70. The resulting text was as follows:

The program is called “Multiverse Explorer” and it is like an animated picture book to let people see different ways events could happen in the real world. It’s similar to asking people to think about all the different ways a story could go, and then helping them to correctly guess what might happen next in the story.

The Multiverse Explorer screen has two parts: a big moving picture on top and a story line at the bottom.

The big picture is a scene looking down from above. Different varieties of Multiverse Explorer could show any kind of scene, e.g., trees, water, animals, people, cars, roads etc. This scene shows two cars, a red and blue car, and when the Multiverse Explorer is working it shows the cars in different places they might go to in the future.

The story line underneath shows what choices the drivers of the red and blue cars might make, as time goes from left to right. A vertical blue bar on the story line moves from left to right to show the order of events happening in the big picture. Whenever a car has a choice of different things to do, the horizontal green or pink band splits in two. If one choice is more likely to happen, that path will be wider.

Multiverse Explorer doesn’t show how events happen in just one way. Instead, it shows many different possibilities all at the same time. The big picture shows faint, transparent cars in different places. These “ghost cars” show the different ways the cars could go (depending on what their driver chooses to do). The more distinct the car looks, the more likely it is that a car will go that way in real-world events. So, a faint ghost car shows events that are less likely to happen than a distinct, solid car.

In the real world we can’t always guess what will happen next, so the Multiverse Explorer helps us see the different possibilities for events and how likely they are.

Based on this description of the system behaviour, and the illustration in Figure 2, Charlie made several observations about how Multiverse Explorer relates to our explorations of Ju/’hoansi ways of talking about the future. Firstly, the temporal ordering of the storyline, illustrated as an abstract path of causal factors or information flows, shares foundational assumptions, and corresponds to principles that might be described in terms of conditional probabilities in Western mathematics. Or, in Charlie’s words, the Multiverse Explorer and the way future is talked about by Ju/’hoansi depend on things that happen in the current situation that gives an indication of what will happen in future.

Secondly, whereas narrative accounts typically focus on a single course of events, the Multiverse Explorer visualisation illustrates a variety of outcomes to be considered. The rendering of an ambiguous future, in which there may be different interpretations of what is seen, can be compared to the visual imagery of the story the man told about the dream of twilight and how Charlie encourages respecting multiple interpretations. In other words, Multiverse Explorer shows how different events could possibly happen all at the same time, like an animated picture book that shows people different ways events could happen in real life.

Thirdly, Multiverse Explorer uncovers eventualities that are relatively unlikely, but which may nevertheless need to be considered and discussed. As Charlie explains, what would probably happen in future is not always obvious, while the Multiverse Explorer helps people to see how different things might take place.

Finally, the Multiverse Explorer was not designed for use in “low-resource settings” and Charlie needed to draw his own conclusions by studying the complex figure, to understand what is going on and distinguish between the good and bad things about it. The Multiverse Explorer requires a custom-built gaming laptop with a high powered GPU, and the constraints of connectivity and bandwidth in the Kalahari prevented Charlie from viewing its interactive behaviour, such as in the video figures included in the earlier technical publication 71.

A pluriversal perspective on the multiverse

To return to the pluriverse, we ask how probabilistic ways of reasoning about the future as a computable multiverse might be compatible with traditional ways of knowing, and potentially appropriated by indigenous cultures and peoples. We have juxtaposed the Multiverse Explorer, a contemporary prototype designed specifically to enable Bayesian modes of reasoning via the PPL paradigm, with traditional modes of talking and story telling among Ju/’hoansi. This brings us to the broader questions of design for the pluriverse, as evident in the broader enterprise of machine learning technologies. Escobar’s ‘dreaming-designing’ draws our attention to the reflexivity of information technologies, being not only things that we make, but also things that determine what can be made. In the so-called ‘knowledge economy’, including the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) anticipated in Southern Africa 72, the role of machine-learning AI in computing the future seems critical. Machine learning means not only dreaming – a speculative alternative destination for globalised digital businesses – but also designing the immediate means by which we proceed, through the construction of AI tools.

The popular discourse of AI, in part encouraged by the inherent lack of interpretability of neural networks, blurs the boundaries between studying something made by humans, and pretending that this artefact is a natural kind, somehow reflecting a universal ‘general’ intelligence. Our agenda of constructing more interpretable machine learning models, through the use of educational and domain-specific PPLs, offers the potential for other descriptions.

When Alan and Nic described machine learning in exchanges with Charlie we emphasised how training involves using old information, such as data about past events, with the result that machine learning systems must act on the basis of what they’ve learned. However, old information might not always be the best guide for the future. For instance, if a machine learned from past events or examples that were unfair or not representative, then the machine would keep making unfair decisions.

Charlie, however, observes that throughout life all new inventions are based on old information, meaning that Ju/’hoansi would consider machine learning as just a new way of doing things. Ju/’hoansi are, naturally, accustomed to continual emergence of technological inventions. They recognise that, as in their own actions and decisions, judgments are made in continuity with, and emerging from established knowledge and prior observation. In this sense, machine learning technologies are not a discontinuity, but rather a new way of doing the kinds of things that people already do.

This article argues there are other ways of understanding the world, in addition to Western science and engineering, that can be valuable for building machine learning tools. Working with communities and their traditional knowledge, not just scientific data, can improve machine learning. We have raised concerns that the way machines predict the future ill-suits the ways humans collaborate, and that machine learning should work with different cultures and ways of thinking to create better tools that work for everyone.

Much of Charlie’s professional work focuses on translating Ju/’hoansi culture and language to people from outside of Nyae Nyae, sensitising him to the way studies are carried out and information is gathered from across the globe, with different machines used to capture and store this information. However, the kinds of integrated infrastructure now familiar in Western contexts are not yet commonly or visibly shaping daily life. Although Ju/’hoansi do not have extensive opportunities to collect data from other people across the globe, their own data has been widely disseminated, not least in the scale of anthropological and popular interest in their lives. The extractive nature of the business arrangements described by Couldry and Mejias as data colonialism 73 are key enablers of the machine learning and data science boom, so finding equitable and reciprocal modes of deploying these technologies seems particularly urgent. Once again, innovation is not necessarily negative, so long as diverse knowledge is used wisely. Ju/’hoansi are perfectly accustomed to integrating things from Western and other African traditions into their life-styles, whether cars, clothing or concrete, when they have the agency to do so.

A major motivation in our collaboration with Charlie over the past 4 years has been that machine learning should be more open to different cultures and ways of understanding the world, and less reliant on data that most people don’t know is being used and secretive calculations. Our work together had first coordinated with the Principal of the Tsumkwe secondary school, where we discussed with the head of mathematics the challenges faced by Ju/’hoansi learners within the existing curriculum, and talked to learners about their experiences of the Western curriculum taught in their schools 74. As Charlie reflects, when numerical reasoning is used to make predictions and to do planning for future developments Ju/’hoansi won’t have any knowledge of it and won’t be able to talk about it. Ju/’hoansi people are not often participating in Western systems of governance, and when they do, they have very little agency. Our commitment to critical technical practice, whether in the deployment of appropriate technologies such as the spinner games, or in the construction of complex artefacts such as Multiverse Explorer, draws attention to the value of “critical inclusion” in the design of more accessible and inclusive end-user computation. Multiverse Explorer may not be (almost certainly will not be) the right answer, and computational approaches to probabilistic reasoning may not be the most pressing of the Ju/’hoansi needs, but these investigations do point to opportunities for critical inclusion as a resistance and response to the hegemonic practices of information governance.

Ju/’hoansi people recognise that in real life things are changing from time to time, and thus it is important that possibilities are considered to adapt to the new changes. Indeed, being prepared for adaptation is essential and characteristic of the Ju/’hoansi experience in responding to circumstances, throughout their history and embedded in their folktales and in practices of hunter-gathering, not only through the pressures of modernity. However, as Charlie says “the immediate future is headscratching”. We can only speculate on how the commercial and governmental priorities of Southern Africa will respond to continued reconfiguration of the knowledge economy through 4IR. While direct encounter with algorithmic governance is not (yet) a common part of Ju/’hoansi life, to the extent now established in the West, it seems certain that continued advances in communications infrastructure and personal digital devices will find them engaged ever more closely with the mechanisms of machine learning. Where the way things work in life are governed by traditional laws working alongside external demands of schooling, banking, health and employment, there is an ever-present risk that Western-style codes of data use may unnecessarily overrule or counteract those traditions. If pluriversal alternatives to machine learning tools offer the opportunity to juxtapose, complement, or even assert the validity of traditional knowledge, probabilistic data processing technologies may well become a practical tool rather than an extractive subjugation.

References

Abebe, Rediet, Kehinde Aruleba, Abeba Birhane, Sara Kingsley, George Obaido, Sekou L. Remy, and Swathi Sadagopan . “Narratives and counternarratives on data sharing in Africa.” In Proceedings of the 2021 ACM conference on fairness, accountability, and transparency (FAccT), pp. 329-341. ACM, 2021.

Agre, Philip E. “Towards a Critical Technical Practice: Lessons Learned in Trying to Reform AI”. In Social Science, Technical Systems and Cooperative Work: Beyond the Great Divide, edited by Geoffrey Bowker, Susan Leigh Star, Les Gasser and William Turner, pp. 131- 157. Lawrence Erlbaum, 1997.

Ascher, Marcia, and Robert Ascher. “Ethnomathematics.” History of science 24, no. 2 (1986): 125-144.

Babbitt, Bill, Dan Lyles, and Ron Eglash. “From Ethnomathematics to Ethnocomputing: Indigenous Algorithms in Traditional Context and Contemporary Simulation.” In Alternative Forms of Knowing in Mathematics: Celebrations of Diversity of Mathematical Practices, eds. Swapna Mukhopadhyay and Wolff- Michael Roth, pp. 205-220, Rotterdam: Sense Publishers, 2012.

Barcham, Manuhuia. “Towards a radically inclusive design–indigenous story-telling as codesign methodology.” CoDesign 19, no. 1 (2021): 1-13.

Bidwell Nicola. J. “Early Thoughts on Epistemic Accountability for AI.”, 2021 https://www.cst.cam.ac.uk/blog/afb21/nic-bidwells-thoughts-epistemic-accountability-ai

Bidwell, Nicola. J., Helen Arnold, Alan F. Blackwell, Charlie Nqeisji, /Kun Kunta and Martin M. Ujakpa. “AI design and Everyday Logics in the Kalahari”. In The Routledge Companion to Media Anthropology pp. 557-569. Routledge, 2022.

Bidwell, Nicola J., and Masbulele Jay Siya. “Situating asynchronous voice in rural Africa.” In Human-Computer Interaction–INTERACT 2013: 14th IFIP TC 13 International Conference, Cape Town, South Africa, September 2-6, 2013, Proceedings, Part III 14, pp. 36-53. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2013.

Bidwell, Nicola J., Thomas Reitmaier, and Kululwa Jampo. “Orality, gender and social audio in rural Africa.” In COOP 2014-Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on the Design of Cooperative Systems, 27-30 May 2014, Nice (France), pp. 225-241. Springer International Publishing, 2014.

Bidwell, Nicola J., Thomas Reitmaier, Carlos Rey-Moreno, Zukile Roro, Masbulele Jay Siya, and Bongiwe Dlutu. “Timely relations in rural Africa.” IFIP 2013 Conferences, 2013.

Biesele, Megan. Women like meat: the folklore and foraging ideology of the Kalahari Ju/’hoan. Witwatersrand University Press; Indiana University Press, 1993.

Biesele, Megan (2016). It takes both Sides of the Digital Divide: the Ju|’hoan Transcription Group. Last Whispers. Online: https://www.lastwhispers.org/juhoan

Biesele, Megan, and Hitchcock, R. K. The Ju/’hoan San of Nyae Nyae and Namibian independence: development, democracy, and indigenous voices in Southern Africa. Berghahn Books, 2022.

Blackwell, Alan F., Nicola J. Bidwell, Helen L. Arnold, Charlie Nqeisji, /Kun Kunta and Martin M. Ujakpa. “Visualising Bayesian Probability in the Kalahari.” In Proceedings of the 32nd Annual Workshop of the Psychology of Programming Interest Group (PPIG), 2021.

Blackwell, Alan F., Luke Church, Martin Erwig, James Geddes, Andy Gordon, Maria Gorinova, Atilim Gunes Baydin, Bradley Gram-Hansen, Tobias Kohn, Neil Lawrence, Vikash Mansinghka, Brooks Paige, Tomas Petricek, Diana Robinson, Advait Sarkar, Oliver Strickson. “Usability of Probabilistic Programming Languages.” In Proceedings of the Psychology of Programming Interest Group (PPIG), Newcastle, 2019.

Blackwell, Alan F., Alex Raymond, Colton Botta, Matthew Keenan and Will Hayter-Dalgliesh. “Domain-specific probabilistic programming with Multiverse Explorer.” In Proceedings of IEEE Visual Languages and Human-Centric Computing (VL/HCC) (2023), pp. 124-132. DOI 10.1109/VL-HCC57772.2023.00022

Brown, Barry. “The social life of autonomous cars.” Computer 50, no. 2 (2017): 92-96.

Bryan, Joe and Diego Melo. “Review of Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds, by Arturo Escobar.” Journal of Latin American Geography 19 no. 3 (2020): 353-356.

Chimakonam, Jonathan O. Ezumezu: A system of logic for African philosophy and studies. Springer, 2019.

Couldry, Nick and Ulises A. Mejias. The costs of connection: How data is colonizing human life and appropriating it for capitalism. Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press, 2020.

Devylder, Simon. “The archipelago of meaning: Methodological contributions to the study of Vanuatu sand drawing.” The Australian Journal of Anthropology 33, no. 2 (2022): 279-327.

Dillon, Sarah, and Claire Craig. Storylistening: Narrative evidence and public reasoning. Routledge, 2021.

Dillon, Sarah, and Jennifer Schaffer-Goddard. “What AI researchers read: the role of literature in artificial intelligence research.” Interdisciplinary Science Reviews 48, no. 1 (2023): 15-42.

Dourish, Paul. “Implications for design”. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human Factors in computing systems, pp. 541-550. ACM, 2006.

Dutta, Urmitapa, Abdul Kalam Azad, and Shalim M. Hussain. “Counterstorytelling as epistemic justice: Decolonial community‐based praxis from the global south.” American journal of community psychology 69 nos. 1-2 (2022): 59-70.

Eglash, Ron., Mukkai Krishnamoorthy, Jason Sanchez, and Andrew Woodbridge. “Fractal simulations of African Design in Pre-College Computing Education.” ACM Transactions on Computing Education 11 no. 3 (2011) Article 17.

Eglash, Ron., Audrey Bennett, Laquana Cooke, William Babbitt, and Michael Lachney. “Counter-hegemonic computing: Toward computer science education for value generation and emancipation.” ACM Transactions on Computing Education (TOCE) 21 no. 4 (2021): 1-30.

Escobar, Arturo. Designs for the pluriverse: Radical interdependence, autonomy, and the making of worlds. Duke University Press, 2018.

Fricker, Miranda. Epistemic injustice: Power and the ethics of knowing. Oxford University Press, 2007.

Fricker, Miranda. “Evolving concepts of epistemic injustice”. In Kidd, I.; Medina, J.; and Jr, G. P., eds., Routledge Handbook of Epistemic Injustice, Routledge Handbooks in Philosophy, pp. 53–60. Routledge, 2017.

Gage, Jenny, and David Spiegelhalter. Teaching probability. Cambridge University Press, 2016.

Gerbault, Pascale, Robin G. Allaby, Nicole Boivin, Anna Rudzinski, Ilaria M. Grimaldi, J. Chris Pires, Cynthia Climer Vigueira, Dobney K, Gremillion KJ, Barton L, Arroyo-Kalin M, Purugganan MD, Rubio de Casas R, Bollongino R, Burger J, Fuller DQ, Bradley DG, Balding DJ, Richerson PJ, Gilbert MT, Larson G, Thomas MG. (2014) “Storytelling and story testing in domestication.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111, no. 17 (2014): 6159-6164.

Gordon, Robert. The Bushman myth: the making of a Namibian underclass. Routledge, 2018.

Jaynes, Edwin T. “Bayesian Methods: General Background”. In Justice, J. H. (ed.). Maximum-Entropy and Bayesian Methods in Applied Statistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986.

Hays, Jennifer, and Robert Hitchcock. “Land and resource rights in the Tsumkwe Conservancies–Nyae Nyae and N‡ a Jaqna.” Neither here nor there” Indigeneity, Marginalisation and land rights in post-independence Namibia, edited by Willem Odendaal and Wolfgang Werner. Windhoek: Legal Assistance Centre, 2020.

Heckler, Melissa A. “The Story Mind: Education for Democracy: Reflections on the Village Schools Project, 1990-2015.” Senri Ethnological Studies 99 (2018): 31-49.

Henrich, Joseph, Steven J. Heine, and Ara Norenzayan, “The weirdest people in the world?” Behavioral and brain sciences 33, no. 2-3 (2010): 61-83.

Hitchcock, Robert K., Wayne A. Babchuk, and Judith Frost. “San traditional authorities, communal conservancies, conflicts, and leadership in Namibia.” Challenging Authorities: Ethnographies of Legitimacy and Power in Eastern and Southern Africa (2021): 267-291.

Hitchcock, Robert K. and Megan Biesele. “Controlling Their Destiny: Ju/’hoansi of Nyae Nyae,” Cultural Survival Quarterly 26, no. 1 (2002): 13-15.

Keeney, Bradford and Hillary Keeney. “Reentry into First Creation: a contextual frame for the Ju/’hoan Bushman performance of puberty rites, storytelling, and healing dance.” Journal of Anthropological Research 69, no. 1 (2013): 65-86.

Keskinen, Pietari, Marley Samuel, Helena Afrikaneer, and Heike Winschiers-Theophilus. “A community-initiated website development project: promoting a San community campsite initiative.” In Proceedings of the 3rd African Human-Computer Interaction Conference: Inclusiveness and Empowerment, pp. 1-11. 2021.

Kotut, Lindah, and D. Scott McCrickard. “Winds of Change: Seeking, Preserving, and Retelling Indigenous Knowledge Through Self-Organized Online Communities.” In Proceedings of the 2022 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, pp. 1-15. 2022.

Kotut, Lindah, Neelma Bhatti, Taha Hassan, Derek Haqq, and Morva Saaty. “Griot-Style Methodology: Longitudinal Study of Navigating Design With Unwritten Stories.” In Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, pp. 1-14. ACM, 2024.

Laws, Megan. All things being equal: uncertainty, ambivalence and trust in a Namibian conservancy. PhD Thesis London School of Economics and Political Science, 2019.

The Legal Assistance Centre (LAC) and Desert Research Foundation of Namibia (DRFN) Reassessment of the Status of the San in Namibia (2010 – 2013), 2014.

Lessig, Lawrence. Code and other laws of cyberspace. New York: Basic Books, 1999.

Liebenberg, Louis. The origin of science. Cape Town: CyberTracker, 2013.

Lunn, David, David Spiegelhalter, Andrew Thomas, and Nicky Best. “The BUGS project: Evolution, critique and future directions.” Statistics in medicine 28, no. 25 (2009): 3049-3067.

MacKay, David. Information theory, inference and learning algorithms. Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Marshall, Lorna. The !Kung of Nyae Nyae. Harvard University Press, 1976.

Muldoon, James, Callum Cant, Boxi Wu, and Mark Graham. “A typology of artificial intelligence data work.” Big Data & Society 11, no. 1 (2024).

Mwewa, Lameck, and Nicola Bidwell. “African narratives in technology research & design.” In Nicola Bidwell and Heike Winschiers-Theophilus (eds) At the intersection of indigenous and traditional knowledge and technology design 353, 2015.

Ofuasia, Emmanuel. “Helen Verran and the Question of African Logic.” History and Philosophy of Logic (2024): 1-10.

Olojede, Helen Titilola and Ayo Fadahunsi, “On Decolonising Artificial Intelligence.” Àgídìgbo: ABUAD Journal of the Humanities 12 No. 1, (2024): 269-282

Oluwole, Sophie Bosede. Socrates and Ọ̀rúnmìlà: Two Patron Saints of Classical Philosophy, Lagos: Ark Publishers, 2014.

Pearl, Judea and Dana Mackenzie. The Book of Why: The New Science of Cause and Effect. New York: Basic Books, 2018.

Ramsey, Frank P. “Truth and Probability (1926)”, in Ramsey, 1931, The Foundations of Mathematics and other Logical Essays, Ch. VII, p.156-198, edited by R.B. Braithwaite, London: Kegan, Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company. (1999 electronic edition, http://www.fitelson.org/probability/ramsey.pdf)

Reitmaier, Thomas, Nicola J. Bidwell, and Gary Marsden. “Field testing mobile digital storytelling software in rural Kenya.” In Proceedings of the 12th international conference on Human computer interaction with mobile devices and services (MobileHCI), pp. 283-286. 2010.

Rey, Josephine, Gemma Penson, Alan F. Blackwell, Hong Ge, Xinyue Li and Helen Arnold. “Educational Tools for Probabilistic Machine Learning Curriculum in Schools.” In Proceedings of the 35th Annual Workshop of the Psychology of Programming Interest Group (PPIG), Liverpool, 2024.

Shanahan, Murray. “Talking about Large Language Models.” Communications of the ACM 67, no. 2 (2024): 68–79. https://doi.org/10.1145/3624724.

Sherman, Rachel E., Steven A. Anderson, Gerald J. Dal Pan, Gerry W. Gray, Thomas Gross, Nina L. Hunter, Lisa LaVange et al. “Real-world evidence—what is it and what can it tell us.” N Engl J Med 375, no. 23 (2016): 2293-2297.

Simon, Herbert A. The sciences of the artificial. MIT press, 1969.

Smith, Linda Tuhiwai. Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2021.

Spiegelhalter, David J. “Probabilistic Reasoning in Predictive Expert Systems.” Machine Intelligence and Pattern Recognition 4 (1986): 47-67.

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. “Can the subaltern speak?” In C. Nelson & L. Grossberg (Eds.), Marxism and the interpretation of culture, pp. 21–78. University of Illinois Press, 1988.

Standley, Peta-Marie, Nicola J. Bidwell, Tommy George Senior, Victor Steffensen, and Jacqueline Gothe. “Connecting communities and the environment through media: doing, saying and seeing along Traditional Knowledge revival pathways”. 3CMedia: Journal of Community, Citizen’s & Third Sector Media & Communication, 5 (2009).

Strathern, Marilyn. “Counting generation(s).” Interdisciplinary Science Reviews 46, no. 3 (2021): 286-303.

Sugiyama, Michelle Scalise. “Information is the Stuff of Narrative.” Style 42, nos.2-3 (2008): 254-260.

Sugiyama, Michelle Scalise, and Lawrence Sugiyama. “A frugal (re) past: Use of oral tradition to buffer foraging risk.” Studies in the Literary Imagination 42, no.2 (2009): 15-41.

Tribus, Myron. Thermodynamics and thermostatics: An introduction to energy, information and states of matter, with engineering applications. (Princeton, NJ: D. Van Nostrand, 1961), p. 64.

UNESCO Harare Office (2022). Landscape study of AI policies and use in Southern Africa: research report. UNESCO Regional Office for Southern Africa https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000385563.locale=en

Verran, Helen. Science and an African logic. University of Chicago Press, 2001.

Wiessner, Polly “The rift between science and humanism: What’s data got to do with it?” Current anthropology 57, no. S13 (2016): S154-S166.

Wiessner, Polly. “Owners of the Future? Calories, Cash, Casualties and Self-sufficiency in the Nyae Nyae Area between 1996-2003”. Review of Visual Anthropology 19 (2003): 149-159.

Zips, Werner and Manuela Zips-Mairitsch. “Pricing Nature and Culture. On the Bewildering Commodification of the African Frontier – an Introduction” in Zips, W. and Zips-Mairitsch, M. (eds), Bewildering Borders. The Economy of Conservation in Africa. 1-34. Munster: LIT Verlag, 2019.

Zuboff, Shoshana. The age of surveillance capitalism: The fight for a human future at the new frontier of power. London: Profile books, 2019.

Notes

- Arturo Escobar, Designs for the pluriverse: Radical interdependence, autonomy, and the making of worlds (Duke University Press, 2018) ↩

- Joe Bryan and Diego Melo, “Review of Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds, by Arturo Escobar.” Journal of Latin American Geography 19 no. 3 (2020): 353-356 ↩

- Edwin T. Jaynes, “Bayesian Methods: General Background,” in Maximum-Entropy and Bayesian Methods in Applied Statistics, ed. J.H. Justice (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986). ↩

- Frank P. Ramsey, “Truth and Probability (1926)”, in The Foundations of Mathematics and other Logical Essays, ed. R.B. Braithwaite, (London: Kegan, Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1931) ↩

- Murray Shanahan, “Talking about Large Language Models,” Communications of the ACM 67, no. 2 (2024): 68–79. ↩

- Judea Pearl and Dana Mackenzie, The Book of Why: The New Science of Cause and Effect (New York: Basic Books, 2018) ↩

- Josephine Rey et al, “Educational Tools for Probabilistic Machine Learning Curriculum in Schools,” in Proceedings of the 35th Annual Workshop of the Psychology of Programming Interest Group (PPIG), Liverpool, 2024 ↩

- Alan F. Blackwell et al, “Usability of Probabilistic Programming Languages,” in Proceedings of the Psychology of Programming Interest Group (PPIG), Newcastle, 2019 ↩

- Philip E. Agre, “Towards a Critical Technical Practice: Lessons Learned in Trying to Reform AI,” in Social Science, Technical Systems and Cooperative Work: Beyond the Great Divide, ed. Geoffrey Bowker, et al. (Lawrence Erlbaum, 1997) ↩

- David MacKay, Information theory, inference and learning algorithms (Cambridge University Press, 2003) ↩

- MacKay, Information theory ↩

- Pearl, The Book of Why ↩

- David J. Spiegelhalter, “Probabilistic Reasoning in Predictive Expert Systems,” Machine Intelligence and Pattern Recognition 4 (1986): 47-67 and David Lunn et al, “The BUGS project: Evolution, critique and future directions,” Statistics in medicine 28, no. 25 (2009): 3049-3067 ↩

- Jenny Gage and David Spiegelhalter, Teaching probability (Cambridge University Press, 2016) ↩

- Emmanuel Ofuasia, “Helen Verran and the Question of African Logic” History and Philosophy of Logic (2024): 1-10 ↩

- Jonathan O. Chimakonam, Ezumezu: A system of logic for African philosophy and studies (Springer, 2019) ↩

- Marcia Ascher and Robert Ascher, “Ethnomathematics,” History of Science 24, no. 2 (1986): 125-144 ↩

- See, for example, Marilyn Strathern, “Counting generation(s),” Interdisciplinary Science Reviews 46, no. 3 (2021): 286-303; or Simon Devylder, “The archipelago of meaning: Methodological contributions to the study of Vanuatu sand drawing,” The Australian Journal of Anthropology 33, no. 2 (2022): 279-327 ↩

- Bill Babbitt et al “From Ethnomathematics to Ethnocomputing: Indigenous Algorithms in Traditional Context and Contemporary Simulation,” in Alternative Forms of Knowing in Mathematics: Celebrations of Diversity of Mathematical Practices, eds. Swapna Mukhopadhyay and Wolff- Michael Roth (Rotterdam: Sense Publishers, 2012) ↩