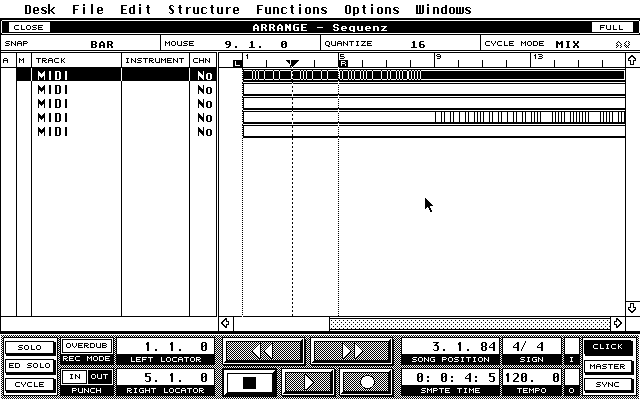

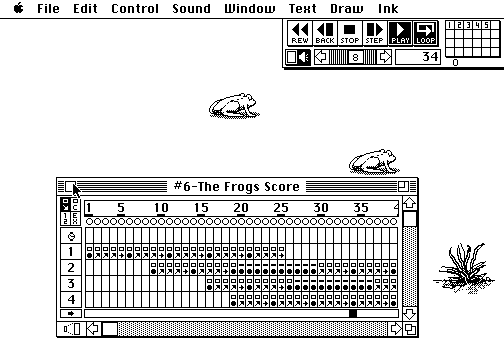

The initial release of the Atari ST musical sequencing program Cubase by the German software company Steinberg in April 1989 marks a significant moment not only for computer music but the development of digital multimedia as a whole. The features established by Cubase, in particular its ‘innovative graphical tracks and timeline interface’ (see Figure 1), were crucial for electronic musicians.1 In a 1995 interview with company founder Karl Steinberg, Paul White notes that ‘Cubase was a totally new concept in graphical interfaces’ and ‘obviously a very successful interface, because all your major competitors have adopted some variation on it for their own products.’2 Furthermore, as many have noted, this type of interface not only became standard within musical composition software, but was adopted by products devoted to producing digital media that are not primarily sonic, making this way of working with information a key aspect of multimedia creators’ workflows.3 For instance, the vector-based program that would become multimedia authoring software Director’s lighter, more versatile cousin Flash after being acquired by Macromedia in 1996 employed a timeline/arrangement-style visualization from its beginnings under the name CelAnimator.4 Today, even as classic multimedia design programs like Director and Flash have become obsolete, such elements persist not only in musical software programs like Reason Studios’ Reason, Ableton’s Live, and Apple’s GarageBand and Logic Pro (another program with roots in the Atari ST), but in suites like the latter company’s Final Cut Pro, a digital video editing program itself originally developed by Macromedia.

Yet it was not Macromedia or any other explicitly multimedia-oriented company that would codify this approach for personal computer software. Demonstrated as Cubit at Frankfurt Musikmesse in late January 1989, where the music technology press noted its ‘impressive use of interactive graphic editing techniques,’ this name emphasized the visual and metrical qualities associated with the ancient unit of measurement representing the distance between the head and extended hand of the monarch.5 Although Cubit would not be its release name, the conflation of visuality, quantification, and sovereign control it sought to evoke—emblematic of graphical user interfaces for scholars like Wendy Hui Kyong Chun—remained a defining feature of the shipping product.6 Drawing in part on geographer David Harvey, Chun argues that GUIs in general are ‘a powerful response to,’ rather than a cause or result of ‘postmodern/neoliberal confusion.’7 Harvey argues that, while rising in the wake of economic factors like the detachment of the U.S. dollar from the gold standard in the early 1970s, neoliberalism can also be understood (as I have noted elsewhere) as a channeling of the radical, yet individualistic 1960s that ‘really only converged as a new orthodoxy with the articulation of what became known as the “Washington Consensus” in the 1990s.’8 Although he gives little attention to specific hardware or software, Harvey’s contention that ‘(i)nformation technology is the privileged technology of neoliberalism’ finds confirmation not only in Chun’s analysis but Fred Turner’s, which traces the antiauthoritarian youth culture of the 1960s through to the rise of WIRED magazine in the 1990s.9 Thus, if Chun’s example of the Stanford Research Institute’s 1968 oN-Line System or, perhaps, the Xerox Alto’s formative 1973 GUI are representative of that former moment, the innovations of their late-’80s heirs—the full-color graphical interface made default with the Macintosh IIci in 1989 on the one hand and Cubase’s establishment of a common set of interface elements for the manipulation of digital multimedia in the same year on the other—are apposite to the latter.

Specifically, these technological developments reflect the solidification of a framework wherein all permutations of digital mediation, at least thus far, can play out, an enclosed conceptual space within which every subsequent event that passes through discrete, electronic encoding can transpire. Jimmy Maher, in his history of the Commodore Amiga personal computer, notes that, while the term ‘multimedia’ had long been associated with mixed-media art, especially of the 1960s performance variety, and although the Amiga, first introduced in 1984, holds a significant technological claim, ‘(t)he term multimedia came to be commonly associated with computing technology…only in 1989, when the arrival of reasonably good graphics cards, affordable sound cards, and CD read-only memory (CD-ROM) drives first began to transform the heretofore bland beige world of IBM and Apple.’10 The mainstream arrival of multimedia thus coincides temporally not only with the neoliberal Washington Consensus, but also, and more conceptually, with political theorist Francis Fukuyama’s famous thesis, first presented that same year, that history, in the Hegelian sense of the idealistic progression of human social organization, had arrived at a conclusion. What progress remained, for him, was only the proliferation of ‘a universal homogeneous state’ consisting of ‘liberal democracy in the political sphere combined with easy access to VCRs and stereos in the economic.’11 Fukuyama’s contention, as is widely understood, was given credence by the breakdown of Soviet-style state socialism by the end of the year, beginning with the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989. Taken together, this set of developments set the stage for the paradoxical ascendance of a ‘universal’ global economy and culture, as Fukuyama predicted, but one predicated, contrarily, around neither homogeneity nor analog media but rather the heterogeneous, discrete medium of binary encoding.

While on the one hand the basis of information theory in World War II radiotelephonic cryptography and Bell Labs suggests that sound holds a privileged position in studies of digitality, on the other it is from the realm of music that many of the most provocative engagements with Fukuyama’s legacy have come.12 In keeping with the tendency of music critics to have anticipated—in a cruel dialectical inversion of Jacques Attali’s 1970s analysis of music as predictive of a future communal society13—our present moment of stagnation and decline, the musical software of the late 1980s can offer critical insights into the arrival of a new paradigm aptly summarized, as its shorthand ‘the end of history’ suggests, in terms of temporality. Lev Manovich’s analysis of Adobe Photoshop, another early multimedia program originally released (as Barneyscan XP) in 1989, notes that ‘(t)he use of layers in media software to separate different elements of a visual and/or temporal composition strongly parallels the earlier practice of (analog) multitrack audio recording.’14 However, the temporo-spatial interplay inherent in manipulating digital audiovisual recordings, as opposed to the strictly spatial nature of still image layering, requires further consideration and historical contextualization. Indeed, despite its temporal fixity Photoshop can even be seen as an inheritor of Cubase’s interface paradigm, as Manovich notes that it did not gain layering capabilities until 1994.

At the same time, as the roots of these interfaces in electromagnetic recording control elements suggest, there is something contradictory about multimedia as the incipient replacement for the era’s supposedly regnant ‘VCRs and stereos.’ ‘Digital multimedia’ indexes discrete encoding’s ability to supplant these largely analog technologies at the same time that it remains largely dependent upon the frameworks of the so-called ‘old media’ which, as Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin have pointed out, it remediates.15 Yet, as Manovich has argued, informationalization ‘allows for the definition of various operations that work on any signal or any set of numbers – regardless of what this signal or numbers may represent (images, video, student records, financial data, etc.).’16 Viewed in this light, the sonic basis of digital mediation, the temporal effects of a near-global proliferation of neoliberal capitalism, and the advent of consumer-grade multimedia converge in Cubase.

Partly for reasons of convenience and partly as a demonstration of theory in practice, Cubase and its antecedents are examined here via a variety of software emulators. Emulation can be inexact, but at the same time has achieved a level of broad functionality, making it particularly suitable for the consideration of surface-level interface elements at issue here. In particular, I have used the Mini vMac (Classic Macintosh) and Hatari (Atari ST) emulators to recreate late-1980s personal computing environments.17 I have not always been able to locate the earliest versions of some programs for use with these emulators; most notably, the earliest version of Cubase I have been able to track down is 1.51, which displays ‘Feb 28 1990 17:40:46’ when loading, although its splash screen copyright dates it to the same year as the initial release, 1989. Nevertheless, an emulated media archaeology of timeline interfaces can shed light on a technical basis for the emergence, out of a process catalyzed via the post-Bretton-Woods semiotization of the world’s global reserve currency, of an ostensibly terminal stage of history with which digital mediation is fully imbricated. This foundation, further, shares an affinity with perspectives on time and mediation, in the tradition of French philosopher Henri Bergson, that have been especially influential within the cultures of electronic dance music, particularly in the United Kingdom, most associated with early versions of Cubase.

Conceptualizing Temporal Totality

Along with Akai hardware samplers from 1988, which made timestretching, a sonic effect dissociating the length of a sound from its pitch, accessible to independent electronic music producers, Cubase was a key piece of technology for the music that arose in the wake of the importation of Chicago acid house and Detroit techno to Europe.18 In particular, the software’s influence on British post-rave culture is reflected in one of the key figures of early-1990s British dance music, Dan Donnelly. The founder of the influential Suburban Base label and affiliated Subbase Studios, whose output charts the subculture’s transition from hardcore techno to jungle/drum’n’bass, Donnelly chose to reference the sequencer by releasing his own productions under the alias QBass. This debt continues long beyond the standard shelf life of software; for instance, the CD version of the UK garage/proto-dubstep collective Horsepower Productions’ 2002 debut album, In Fine Style, features a picture of an Atari ST on its back cover running an early version of the software. While Joshua Clover has argued that the British acid house and rave cultures emblematize a Fukuyaman ‘desire for a time that is not in time, a unity outside history,’ drawing on the reflections of Mancunian electronic music pioneer A Guy Called Gerald to note the specific contribution of sampling, as repurposed time, to this aesthetic,19 a slightly different story has generally been told about the post-rave embrace of Cubase, particularly as the musical artists and developments it inspired have in turn been adopted by philosophically informed cultural theorists.

Emblematic of this approach is an embrace of the theoretical framework offered by French philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari. While on the continent, most representative is the German electronic music label Mille Plateaux, named after the second volume of Deleuze and Guattari’s Capitalism and Schizophrenia project, in the UK it is the Cybernetic Culture Research Unit.20 Kodwo Eshun, an Afrofuturist thinker formerly associated with the latter group, for example, writes that ‘(j)ungle accepts the rigidly quantizing function of the Cubase virtual studio. It doesn’t revolt against the grid; it optimizes it into new possibilities.’21 American fellow-traveler Erik Davis argues that ‘(i)n the early and mid-1990s, when digital culture reached perhaps the most vital and open-ended phase we have yet to see…much of (jungle) was generated entirely on personal computers loaded with Cubase and a fat folder of sound files.’22 Yet, as the (non-CCRU-affiliated) geographer Nigel Thrift points out, an increasingly digital environment fosters ‘a new “technological unconscious” whose content is the bending of bodies-with-environments to a specific set of addresses without the benefit of any cognitive inputs.’23 This kind of adaptation is critical for influential human–computer interaction theorist Brenda Laurel, whose conception of interfaces as a productive set of limitations Chun builds upon to argue that the not-entirely-accurate ‘sense that users control the action and make free and independent choices within a set of rules’ represents ‘the classic neoliberal scenario.’24 The embrace of Cubase’s overarching framework, its ‘grid,’ facilitated the dynamism of the genres made under this powerful new tool’s approach to composition and, indeed, time. Simultaneously, it is symptomatic of a larger adoption of the temporo-political precepts represented by the ‘end of history’ and technologically enacted by digital multimedia.

Thrift’s description of a ‘qualculative world,’ a physical space and corresponding temporality so imbricated with electronic sensors and other computing technologies that, via such addressing, ‘all parts of the system are able to be located by all other parts,’ goes beyond but is also, as he makes clear, enabled by ‘the spread of the interfaces and defaults of computer software, which both encapsulated the new possibilities and acted as a vehicle for them.’25 In the article he cites on this latter point, ‘new forms of music using musical instrument digital interfaces (MIDI)’ are examples, and ‘complex contemporary multimedia programs like Director’ enablers, of software’s ability, beyond generating ‘defined and determined responses,’ to be ‘an experimental tool’ fostering ‘a tending of the virtual.’26 This latter term he and Shaun French take from Pierre Lévy, who in turn takes it from Deleuze,27 whose own usage of it is itself imbricated with that of the late-19thand early-20th-century French philosopher Henri Bergson. The sense of ‘creative potential’ with which the concept of the virtual is imbued can be seen, for example, in Bergson’s description of perception: ‘an object distinct from our body, separated from our body by an interval, never expresses anything but a virtual action. But the more distance decreases between this object and our body (the more, in other words, the danger becomes urgent or the promise immediate), the more does virtual action tend to pass into real action.’28 Qualculation, for Thrift, is heir to ‘(the) idea of spaces that fold and flow,’ including ‘Bergson’s philosophy’: ‘What is different, however, is that the means to realize this world have now come into being as a result of much enhanced calculation, allowing all kinds of entities which could be imagined but not actualized finally to make their way into the world.’29 By his own admission, this computational geographic space is (and arguably remains today) in many ways nascent but is, equally, anticipated by the software and interfaces of the multimedia age.

Sonic theorist and CCRU member Steve Goodman directly connects both the software timeline and timestretched sampling with Bergson. The timeline, and timestretching, Goodman argues, although stemming from the highly quantified realm of the digital, open up alternative temporal possibilities less in line with notions of sequential progression than Bergson’s concept of duration, or durée:

“Typical objections to the ontology of the digital temporality share much with the philosophy of Henri Bergson…Bergson criticized the cinematographic error of Western scientific thought, which he describes as cutting continuous time into a series of discreet (sic) frames, separate from the temporal elaboration of movement, which is added afterward (via the action, in film, of the projector) through the perceptual effect of the persistence of vision…The sequencer timeline is one manifestation of the digital coding of sound, which, while breeching (sic) Bergson’s spatialization of time taboo…has opened a range of possibilities in audiovisual production. The timeline traces, in Bergsonian terms, an illusory arrow of time, overcoding the terrain of the sequencing window from left to right…The temporal parts and the whole of a project are stretched out to cover an extensive space…What is opened up by this spatialization is the ease of temporal recombination. That marker of the transitory present, the cursor, and its ability to travel into the future and past (the right or left of the cursor) melts what appears, at least within the Bergsonian schema, to be the freezing of audio time into spatialized time stretches, instead of intensive durations. This arrangement facilitates nonlinear editing by establishing the possibility of moving to any point, constituting the key difference between nonlinear digital editing and analog fast forwarding and rewinding.”30

The timeline, in other words, relativizes time in a way that goes beyond its mere reduction to interchangeable zeroes and ones. It does temporally what addressing, for Thrift, does spatially, making any point in time conceptually (virtually) equidistant from any other. In so doing, it reveals less an opposition between duration and technical media than a constitutive and indeed dialectical paradox: durée, the objectively qualitative inseparability of space and time, is achieved not so much in contrast to the spatialization of time as it is through its hypostatization. This is certainly the case for Thrift’s more physically-oriented conceptualization, in which ‘new sensings of space and time…would be impossible without the fine grid of calculation which enables them: they are not, as many writers would have it, in opposition to the grid of calculation but an outgrowth of the new capacities that it brings into existence. A carefully constructed absolute space begets this relative space.’31

For Bergson, ‘(d)uration is the continuous progress of the past which gnaws into the future and which swells as it advances,’ an understanding of the past as informing the present and future, which essentially consist of its permutations.32 Even if these iterations are unanticipatable, for Bergson they are nevertheless organized by a basic structure operating at a level beneath perception:

Doubtless, my present state is explained by what was in me and by what was acting on me a moment ago. In analyzing it I should find no other elements. But even a superhuman intelligence would not have been able to foresee the simple indivisible form which gives to these purely abstract elements their concrete organization. For to foresee consists of projecting into the future what has been perceived in the past, or of imagining for a later time a new grouping in a new order, of elements already perceived. But that which has never been perceived, and which is at the same time simple, is necessarily unforeseeable.33

Further, he argues that, from this perspective, the classical philosophical distinction between subject and object is fundamentally meaningless: ‘there is no essential difference between the light (i.e. subjective perception) and the movements (i.e. objective matter), provided we restore to movement the unity, indivisibility, and qualitative heterogeneity denied to it by abstract mechanics; provided also that we see in sensible qualities contractions effected by our memory.’34 Contemporary thinkers drawing upon Bergson typically emphasize this idea and, consequently, the extension of duration beyond the subject and against ‘the homogeneous space and time which we stretch out beneath (things) in order to divide the continuous, to fix the becoming, and provide our activity with points to which it can be applied.’35

Deleuze, for example, argues that ‘Bergsonism has often been reduced to the following idea: duration is subjective, and constitutes our internal life…But, increasingly, he came to say something quite different: the only subjectivity is time, non-chronological time grasped in its foundation, and it is we who are internal to time, not the other way round…Time is not the interior in us, but just the opposite, the interiority in which we are,’ rendering time itself affective.36 Deleuze’s analysis of cinema, like Goodman’s of the timeline, admits its contradiction with Bergson’s opposition to metrical mediation in order to disavow it: ‘is not the reproduction of the illusion in a certain sense also its correction?…Cinema proceeds with photogrammes…(b)ut it has often been noted that what it gives us is not the photogramme; it is an intermediate image.’37 Yet, it is precisely these texts that mark the beginning of an engagement between Bergson and media studies in which the late 1980s and early 1990s play a key role. Jeffrey Skoller, for instance, uses Deleuze’s notion of the cinematic time-image to read ‘the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 as a nodal point for the shifts in twentieth-century geopolitics’ in films such as Jean-Luc Godard’s Allemagne année neuf zero (1991): ‘Central to Deleuze’s definition…is the Bergsonian conception of duration in which the past and future are not simply on a continuum but integral to the present.’38

The foundational paradox of this line of inquiry, evacuating technical processes from temporal mediation, has meant that the role of technology in the proliferation of Bergsonian approaches to mediation remains undertheorized. When this problematic is transposed into software studies, and particularly from the perspective of the post-1989 proliferation of Fukuyaman political economy and digitization alike, the contradiction between a discrete ur-medium that invites durational comparisons on the one hand and Bergson’s absolute insistence upon the fundamental indivisibility of duration on the other makes the need for historicization clear. Indeed, despite the significance of Cubase for theorists and critics of rave culture,39 Goodman, who is also a DJ, electronic music producer, and head of a record label rooted in rave culture, focuses on the abstract characteristics of the timeline as user interface element as well as timestretching as mathematical process, omitting these technologies’ arrival in mainstream digital sound and music products in and around 1989.

Abstract Representations of Time

As Goodman notes, ‘the timeline typically stratifies the on-screen workspace into a metric grid, adjustable in terms of temporal scale (hours/minutes/seconds/musical bars or frames/scenes). With sonic timelines, zooming in and out, from the microsonic field of the sample to the macrosonic domain of a whole project, provides a frame for possible sonic shapes to be sculpted in time.’40 Yet the timeline did not always exist across a variety of multimedia interfaces in the form we know it today, and in this regard it is useful to outline its history by way of both music programs specifically and multimedia authoring software more generally. It is not a coincidence that both software and musical patterns are programmed; as Florian Cramer has argued, ‘If software is generally defined as executable formal instructions, logical scores, then…(a) piano score, even a 19th century one, is software when its instruction code can be executed by a human pianist as well as on a player piano.’41 Composer and communications scholar Paul Théberge concurs, writing that, prior to the advent of recording, ‘(i)n a sense, both sheet music and piano rolls could be considered the “software” components of a primarily hardware-driven (music) industry.’42 This connection between composition and programming is also found in Attali’s theorization of the musical score, which draws an analogy with computation (and, further, between computation and labor): ‘the composer produces a program, a mold, an abstract algorithm,’ which ‘musicians—who are anonymous and hierarchically ranked, and in general salaried, productive workers—execute.’43 This is yet another sense in which precedent would seem to afford musical or sonic methods a special place in the register of new media precursors, but also one that understands the timeline as mechanically linked with the action of playback or execution, the interpretation of a score or the transformation from stored media to lived experience.

Instruments with digital control and timing circuitry such as Roland’s classic TB-303 bass synthesizer (1981) and TR-808 (1980) drum machine mark the onset of an inversion such that musical composition is no longer merely a forerunner to programming, but rather, in a very real way, a form of it.44 In terms of the personal computer, Maher describes the advance in ease-of-use represented by MOD tracker programs like the Amiga’s 1990 ProTracker, which, using vertically-scrolling numerical codes to trigger musical events such as timing, pitch, and effects, ‘approaches music making as essentially a programming task.’45 The increasingly computerized nature of electronic music production had by this point already drawn attention to the limitations of physical controls; as Michael Berk notes, with the advent of affordable digital keyboards like the 1983 Yamaha DX7, ‘the increased number of programming parameters needed to access this power meant the end of the simple, hands-on interfaces that had made analog synths so appealing in the first place.’46

This inversion from programming as a form of composition to composition as a form of programming is coterminous with an abstraction of the timeline function from an active element of playback into a representation of playback. This active element can be traced back to human interpretation of musical scores. Théberge, for example, argues that written music

was, from the outset, characterized by a relationship to time that was different from performance; with notation, not only was the musical work preserved in a concrete form, but musical time itself was represented in a spatialized pattern. The ‘urgency,’ anticipation, and shared sense of time characteristic of performance was replaced (for the composer at least) by a detached set of quasi-mathematical calculations and operations executed with little reference to ‘real-time’ modes of action…The representation and manipulation of temporal, dynamic, and tonal relations in recent digital technologies, such as sequencers and drum machines, have much in common with notation and extends the possibilities of rational control even further.47

Cubase’s combination of the temporal and the spatial, the horizontal and the vertical, the diachronic and the synchronic, however, makes its interface particularly noteworthy even within this broader regime of rationality. In contrast to the MOD trackers described by Maher, Cubase represents time horizontally, from left to right, by way of its timeline. However, this return to classical directionality (like, as Goodman notes, a musical score)48 is accompanied by the GUI’s abstraction of execution, for Cubase’s timeline does not directly play the notes it traverses; rather, the Atari sends signals out through its MIDI ports at roughly the same time that it separately draws the line in the horizontal location on screen corresponding to the notes’ presence within compositional time.

Goodman writes that the timeline is ‘(a) common feature of all time-based media,’49 but with analog media this ‘timeline’ is generally electrical, optical, or mechanical rather than representational: from the player piano to the frame of film in front of the camera or projector aperture, the point of contact between needle and vinyl record, the sections of magnetic tape crossing the heads of a video or audio deck, the position of electron beams on a cathode ray tube screen, or, as Thomas Y. Levin has shown in the case of work on film sound in the early 1930s such as that of Swiss artist-technician Rudolf Pfenninger, light projected through an optically-printed waveform registering on a selenium cell. Levin argues that Pfenninger’s method was a crucial moment in ‘a semio-pragmatics of sound whose function was to liberate composition from the constraints of both the extant musical instrumentarium and reigning notational conventions’ via proto-digital ‘discrete units,’ one enabling soundtracks to be drawn in addition to being indexically registered that lead to ‘the invention of new recording media such as magnetic tape and of new synthetic sound technologies…and the later proliferation of MIDI interfaces,’ like Cubase, ‘that have rendered the experience of, and work on, music as a graphic material an almost quotidian affair.’50 Indeed, Levin concludes,

In light of Lev Manovich’s suggestion that in media-historical terms the advent of the digital episteme can be described as a turn from an optical to a graphic mode of representation that in fact characterized the nineteenth-century media out of which cinema was developed…Pfenninger’s synthetic sound technique in turn reveals a key dimension of this graphic turn of new media—its fundamental status not so much as drawing but qua inscription as a techno-logics of writing.51

From the perspective of playback, however, this process is similar to that of projecting a filmic image, and Levin’s focus on sound synthesis makes clear that Pfenninger’s ‘new technique of acoustic notation’ was directly ‘phenomenalized by the selenium cell’ as sound.52 MIDI software thus represents in some sense a dialectical return to the ‘Media-historical coquetry’53 of the gramophone, where, unlike the selenium cell process, the technical writing is too small to work with by hand, but one in which graphical manipulation nevertheless remains possible via the techno-logical abstraction of the interface from sound generation. It is only with digitization that the ‘timeline’ as such, as an abstract representation of playback, appears.

The additional levels of abstraction in the digital conception of the timeline are made clear by Cubase’s addition of an optional multitasking system, M-ROS (MIDI Real-time Operating System), enabling it to synchronize with other MIDI software to ensure that the stream of musical data, and thus the final audio output, is as malleable as possible ‘with a maximum of timing accuracy.’54 However, this supposed ‘real-time,’ as Chun has noted, is anything but, since coordinating multiple input and output streams with separately running programs or even threads replaces a direct, mechanical connection between these events with an appearance of simultaneity.55 As Anne Friedberg has argued more generally, ‘(f)or a computer to multitask, the computer does tasks not simultaneously but serially, and yet at a high speed…While a computer microprocessor can keep many programs running at the same time (parallel processing), the user still “crosscuts” between one or more programs in selective sequence,’56 although computers can and do perform such crosscutting even without user intervention, let alone the GUI interactions that are Friedberg’s focus. In reality, multitasking is distinct from parallelization across multiple CPUs, which at least holds out the possibility of synchronicity;57 on the single-processor personal computers of the multimedia era such as the Atari ST—with or without the added, optional support of M-ROS—MIDI output and the timeline’s display position would be not directly related but tied together via some third term such as clock state and enacted, stricto sensu, at separate points in time. Nevertheless, as Friedberg suggests, ‘(j)ust as the instrumental base for the moving image—the retinal retention of successive virtual images—produced a newly virtual representation of movement and a complex new experience of time, the instrumental base for multiscreen multitasking poses new questions about the computer user’s experience of time.’58

Building on Erwin Panofsky’s analysis of classical perspective, Friedberg sees this newer experience, engendered by the multiple windows of the GUI, as, by contrast, ‘multiple and fractured.’59 Paradoxically, however, at the same time it is only with digital multimedia that the abstract yoking of playback and feedback represented by the timeline is leveraged into a navigable, durational representation of the composition as a whole. Unlike physical electronic instruments or programs representing notes as on-screen numbers, Cubase represents multiple tracks vertically, enabling a view of the composition across both a range of instrumentation and broad time scales. In doing so, the software had to push against the constraints of the period’s consumer-level displays. Combining the timeline with its default ‘Arrange’ view, Cubase uses so much screen area for its visualization that users benefited from running their STs in a special display mode sacrificing color for a higher-resolution, 640×400 monochrome image (see Figure 1).60 Even this is still limited enough to discourage multiple simultaneous windows, albeit without disallowing them (as we will see the composition is meant to be rendered in different views depending on the task at hand).

At this resolution, one could have simultaneous visual access to up to 18 musical tracks (bass, drums, samples, etc.) arranged vertically and 16 measures (in 4/4 time) horizontally. Although it is obviously impossible for any display, no matter how large, to represent a truly infinite amount of either instrumental tracks or musical time, Cubase’s interface provides options for overseeing and containing a massive increase in potential complexity. Users can manage individual tracks and the length of the song by scrolling either vertically or horizontally to see more than the screen allows, and the horizontal view automatically ‘paginates’ during playback, drawing the next screen of measures as the timeline moves beyond the first. Tracks themselves can be subdivided into parts, allowing for easy cutting and pasting of elements like melodies or drum patterns. Similarly, a section of time across all tracks can be blocked off by the use of left and right ‘locators’ alongside the timeline itself, enabling looping and other manipulations. While the Arrange view offers a spatial synopsis of multiple temporal tracks, it is only possible to distinguish individual part lengths and general rhythmic patterns within each part and even this latter feature, although present, does not appear by default to have been enabled in versions prior to 2.0. When it is, small horizontal lines mark the point in time when a note is being hit, but not the value of the note or any other information.

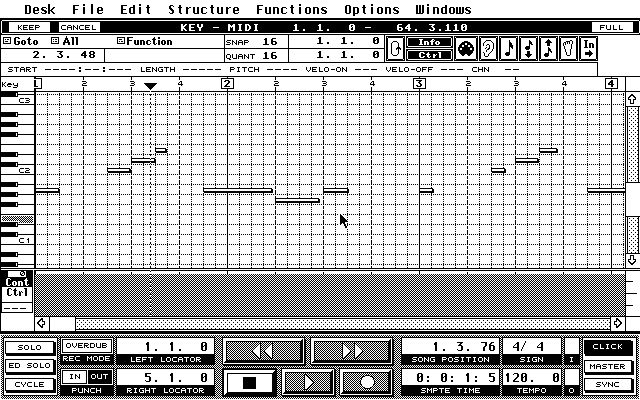

While one could simply press record and enter the notes on an attached instrument such as a keyboard ‘live,’ selecting each part represented on the timeline offers users the ability to make changes to the notes graphically through its other views, such as ‘Drum’ and ‘Key,’ according to what type of instrument an individual track represents (see Figure 2).61 For Théberge, ‘because a computer screen can only display a limited amount of information at any given moment…precise editing…can be performed within a given track but gaining access to the same information across tracks is usually more difficult to achieve. This situation is quite different from that encountered in a full musical score.’62 Yet Cubase does offer a comprehensive system for managing a multi-instrument composition or song at a variety of levels of detail depending on the user’s needs at any given moment. At the same time, it allows users to follow the composition not only with the arrangement view but via the timeline, the thin bar running vertically from the top of the arrangement area down through a key of measures and multiple tracks enumerated below it.

Cubase’s holistic approach to time is especially significant within a moment in which history itself is formally pronounced to have come to an end, when repetition is the only possible difference. Its timeline enables a conception of composition in which individual tracks or parts can be rearranged inside a totalizing overview, subsuming temporality to spatialization, as theorists like Manovich and Chun have argued that digital encoding overall encourages.63 Its specialized views extend this functionality within individual tracks. While samplers and audio formats have to do with the reproduction of sound, Cubase tackles a different problem: that of representation, and specifically the problem of representing musical notation. Although the ability to deal with audio came later, initial releases of Cubase dealt solely with the Musical Instrument Digital Interface standard (MIDI), designed to achieve interoperability between disparate musical equipment in 1983 and principally meant to convey information about notes played rather than sounds themselves.64

Early versions of Cubase thus produce their only significant analog output via the Atari’s video port. The program thus primarily serves as an aid to composition by mediating between different conceptualizations of musical information rather than digitized audio. Users can compose directly from within the interface itself, obviating the need for external input, but, aside from default system beeps (cleverly used to provide a metronome), if sound is produced at all it is by definition a byproduct of the process of articulating musical notation in a variety of electronic and visual formats. However, this does not detract from its status as a multimedia innovator; as Cramer writes, ‘If at all, computer processes become “media” only by the virtue that computers can emulate any machine, including all technical media, and by the virtue of the analog interfaces which transform the digital zeros and ones into analog sound waves, video signals, print type and vice versa.’65 And, as Bolter and Grusin argue, the ‘contemporary hypermediacy’ of the GUI ‘offers a heterogeneous space, in which representation is conceived of not as a window on to the world, but rather as “windowed” itself—with windows that open on to other representations or other media.’66 Cubase’s innovations are thus at the level of interface more than that of rendering digitally-encoded analog content.

Multimedia Interfaces before Cubase

Given the challenges presented in excavating decades-old software for examination, it is difficult to establish definitively that Cubase was the first mainstream software program to use this interface paradigm the way that it did. However, it is simple enough to locate, beyond Maher’s Amiga-specific examples, further antecedents making slightly different use of the same concepts in order to illustrate both the continuities and ruptures that Cubase’s interface represents. Of obvious note, but worth reiterating, is Cramer’s prima facie example of the player piano score, in which a notched piece of paper scrolls through a mechanism that renders the notches into struck notes as they pass by—again, an example of a ‘timeline’ directly imbricated in physical playback. Berk also explicitly makes this connection: ‘recorders of events rather than audio, (sequencers) were latter-day electronic heirs to the punched-paper rolls that drove player pianos,’ as does Théberge, noting its commonality.67 That the opening credits to the premium-cable series remake of the sci-fi-meets-western film Westworld (1973) explicitly evoke this lineage demonstrates the ongoing centrality of these musical predecessors for even the most fantastical contemporary considerations of digitization in robotics and artificial intelligence.

Of course, the mechanical score is not a direct match for the timeline, both on account of its decidedly analog nature and due to the fact that, as with most other analog examples (the CRT being the notable exception) it is only the media and not the playback element that scrolls. Ironically, MIDI itself is a serial protocol that, in a sense, could also be said to follow this model. It is only with the arrival of graphical interfaces like Cubase that it attains a kind of virtual asynchronicity. Yet, by the mid-1980s, interface elements representing both the status of single-track audio playback and visual arrangements of multi-track elements were already common features of multimedia programs.

A close antecedent exists in the very specialized, industrial realm of the mid-1980s Lucasfilm-affiliated, primarily LaserDisc-based EditDroid, which ran on a Sun workstation, facilitating editing between video and audio tracks for film production. Michael Rubin argues that this system, which enabled editors to use a graphical interface instead of ‘just columns of numbers’ in order to produce a final cut out of working footage stored on analog LaserDiscs or videocassettes, ‘introduced the (timeline) concept in its modern incarnation, bitmapped graphics, with synchronized tracks running along indefinitely, able to be selected and manipulated on the screen.’68 Although Rubin credits Industrial Light and Magic engineer Malcolm Blanchard with developing the interface and coining the term ‘timeline,’ EditDroid’s appearance differs from that of the timeline as found in Cubase and/or theorized by Goodman in a few key aspects: firstly, Rubin makes it clear that ‘timeline,’ here, refers not to a vertical indicator of temporal position (what Goodman calls ‘the cursor’) but rather the horizontal spatialization of entire media tracks; secondly, EditDroid’s spatialization maintained skeuomorphic compatibility with analog editing desks by running right-to-left rather than left-to-right; thirdly, the number of tracks visualized by EditDroid was essentially limited to one image track and two audio channels, a much smaller arrangement than the multitrack compositions that Cubase and other multimedia software were meant to enable;69 and finally, EditDroid, in the last instance, relies upon pre-fabricated analog information (e.g., individual video frames on a LaserDisc drawn from the opto-mechanical interface of the movable laser), simply allowing users to resequence the order in which this information is read, rather than the quantitatively more malleable MIDI protocol, which can include two-way communication as well as additional information such as added effects. Further, predecessors like this, for obvious reasons, were not used outside of professional editing.

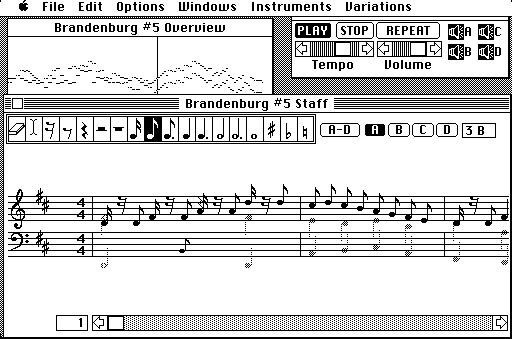

To further understand the significance of the timeline’s popular emergence out of Cubase’s particular implementation, we can instead compare it to other 1980s commercial software interfaces, and particularly those more explicitly associated with digital multimedia. Although differing in significant respects from Cubase’s timeline, important predecessors can be found in three Macintosh software products associated with one of the key developers of multimedia authoring software in the 1980s and 1990s, Macromedia. MusicWorks (1984), the first piece of software released by MacroMind, one of the three major companies that would eventually combine to form Macromedia, has an ‘Overview’ window featuring musical notes played over time, with a moving timeline marking the current position as the piece progresses (see Figure 3). In a 2009 blog post celebrating the 25th anniversary of the software, one of MacroMind’s founders and developers claims it offered the ‘first “overview” of an entire piece, scaled “back.”’70 MusicWorks can deal with four simultaneous ‘tracks,’ labeled A-D, but its overview layers them on top of one another rather than distinguishing them vertically. By default it foregrounds not the Overview but the ‘Staff’ window, emphasizing the representation of the piece being played in traditional musical notation rather than the newer timeline visualization; users have to click on the Overview in order to see it fully, making it a less central feature of the interface. Finally, the Overview window does not paginate when the timeline moves beyond its frame.

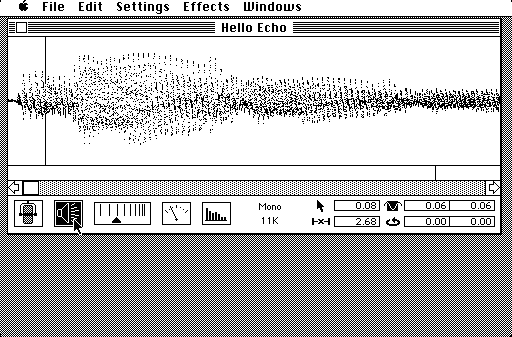

Another interface precursor is Farallon SoundEdit (1988), an early audio editing program for the Macintosh that would subsequently be acquired by Macromedia. Its 2.0.1 version (1989), the oldest I was able to locate, includes both timestretching features and, like some of the more advanced MOD trackers, a timeline-like ‘insertion point’ used to select and modify sections of single-track audio. However, SoundEdit represents playback by way of a small, separate line running below the editing window and just above the interface’s horizontal scroll bar (see Figure 4). By selecting ‘Playback from insertion point’ and/or ‘Record from insertion point’ in the ‘User Options,’ one can choose, to a limited degree, to synchronize these two lines, but only at the start of an interaction. It also does not paginate its overview, although one can ‘block off’ portions of audio by selecting them with the mouse in the visualization to identify loop breakpoints and targets for effects. Especially by default, however, SoundEdit’s method of representing and interacting with time is similar to that of MacroMind’s early multimedia design program VideoWorks (1985).

VideoWorks makes use of a window called (again emphasizing the musical basis of this logic) the ‘score,’ which, like Cubase and unlike MusicWorks or SoundEdit, allows users to visualize and modify the activity of not one but multiple media elements, both as an abstract whole and during playback. Instead of a timeline, however, it uses a small black cube situated at the bottom of the window, described skeuomorphically as a ‘Playback Head’ in the manual, that scrolls along underneath the displayed set of elements rather than across them. Again, the visualized data itself does not automatically paginate to keep up with its travelling, time-keeping marker; during playback it disappears offscreen when the current time exceeds the size of the window. Clicking in the ‘track’ along which the Playback Head travels immediately jumps the head (and thus playback) to that position, allowing for a small amount of ‘real-time’ interaction, but it was only with VideoWorks II (1987) that the window gained an additional element allowing a limited type of pagination: a small arrow button that, when clicked, re-centers the score around the current position of the marker (see Figure 5). Finally, its score represents each frame of animation as a large block, a significantly more granular visualization, like that of some pre-Cubase MIDI sequencers, than the pixel-by-pixel view of MusicWorks, SoundEdit, or Cubase. VideoWorks was the immediate predecessor to Director, a multimedia design application only discontinued by its final publisher, Adobe Systems, in 2017; this method of marking time was still in use up through Macromedia Director 5 (1996), well after the initial release of Cubase.71

Discrete Multimedia Structures, Holistic Space-Time

The relatively common deployment of this motif in all its permutations opens up on an alternate definition of multimedia, one that eschews technological developments for conceptual ones. As Florian Brody argues, given the number of individual technological advances that hold significance for the emergence of multimedia and ‘(l)ooked at historically, it becomes hard to set the point where multimedia begin.’72 This situation is demonstrated by the number of antecedents and descendants described here, to which he adds one more, comparing the visual layout of multimedia design programs to the blueprints that Soviet filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein developed to plot out the visual and sonic movements of his films: ‘Eisenstein’s diagrams for Alexander Nevsky remind me of nothing so much as the scores for interactive multimedia programs like Macromedia Director.’73 For Brody, the timeline, the spatial arrangement accompanying it, and the ability to easily manipulate them become crucial to the concept of multimedia for a reason altogether separate from any technology for incorporating and translating between disparate mediatic forms: ‘True multimediality is…not defined by the concoction of different media types but by the integration of spatial, temporal, and interactional media.’74 Yet Cubase’s precise innovation over Director and, indeed, earlier instances of the timeline more generally, resides in its combination of these definitions. While Director was still marking time with its ‘Playback Head,’ the Cubase model, consisting not simply of vertical tracks and horizontal time but also a line traversing the entire view from top to bottom, one that, furthermore, redrew the arrangement window to follow this timeline’s progress, represented both a conceptual advancement in terms of spatial, temporal, and interactional integration and a more classically, technologically multimediatic innovation: the ability to seamlessly convert between visual and musical information at the level of a complex, multi-layered composition.

For Brody, the conceptual breakthroughs that give rise to ‘true multimediality’ are not automatically accompanied by similarly groundbreaking aesthetic developments, especially in comparison to Eisenstein: ‘While digital media offer themselves to rigorous preplanning, too many multimedia pieces lack the sophistication of an underlying structure, and become sprawling messes…(Eisenstein) offers a model of how an emergent medium finds its parameters. In new media we are not yet at the point where the conceptual interdependence of time and space is being fully exploited.’75 This is, of course, an important point: the instantiation of a medium and the methods and codes developed by its formal innovators to make use of it are—to an extent—separate developments.76 Nevertheless, that Brody should feel comfortable making such a claim well into the 1990s suggests there may be something more at stake.

Put simply, Eisenstein’s innovation in scores like those for Alexander Nevsky (1938) is twofold: designing both the system, or formal schema—‘a tentative film-syntax,’77 as he calls it at one point—and the content inhabiting it. By contrast, with Cubase, as one might expect in a technology beholden to an information-theoretical model wherein, as Warren Weaver, explicating the work of Claude Shannon, famously put it, ‘(t)he concept of information applies not to the individual messages (as the concept of meaning would), but rather to the situation as a whole,’ the formal schema is already defined for the user, with the crucial distinction that it is so vast as to appear practically infinite.78 As Thrift writes more generally, quantification and computation are ‘the real winners of the ontological wars, defining not so much what is to be done in any situation but how the situation turns up in the first place.’79 Despite its discrete, digital character, then, the actual ‘underlying structure’ driving Cubase’s visualizations nevertheless echoes Bergson’s characterization of the ‘simple indivisible form’ that lies beyond perception and guarantees the novelty, within a holistic system, of permuted elements; as Davis puts it in regard to jungle, ‘(n)ovelty lies at least as much in the recombinant rearrangement and pacing of…generic elements as in the generation of novel motifs and sounds.’80 Cubase’s timeline and arrangement elements give further background to Manovich’s claim that ‘(t)he new logic of a digital moving image contained in the operation of compositing’ in programs like Adobe Premiere and After Effects, which use similar interface techniques, ‘runs against Eisenstein’s aesthetics with its focus on time.’81 As its adoption by dance musicians emphasizes, Cubase’s graphical innovations are in service of managing repetition over temporal change.

In contrast to Eisenstein’s attempts to impose order on cinematic raw material, Cubase 1.51 running on an (emulated) Atari ST with one megabyte of RAM—a relatively common configuration for such a machine in 1989—lists a maximum of 45408 ‘events,’ 2838 ‘parts,’ and 17028 ‘groups’ available for composition. The need to develop a further intermediary syntax between that of the system itself and the content it mediates diminishes, for such syntaxes are already available as menu options and internal limitations. As Manovich argues, this technological development defangs the avant-garde.82 Is it any wonder, then, that multimedia systems produce sprawl rather than tautly focused formalism?

In Cubase and its UI successors, as Davis has noted more broadly, Marshall McLuhan’s much-noted association of a post-literate, mediatized world with a saturated sonic environment at odds with fixed, Renaissance perspective is applied visually, even within a single-window ‘Arrange’ view.83 Manovich even goes so far as to assert that ‘(c)omputer multimedia…does not use any montage. The desire to correlate different senses, or to use new media lingo, different media tracks, which preoccupied many artists throughout the twentieth century including Kandinsky, Skriabin, Eisenstein, and Godard…is foreign to multimedia. Instead, it follows the principle of simple addition. Elements in different media are placed next to each other without any attempt to establish contrast, complementarity, or dissonance between them.’84 Cubase’s musical interface, which ultimately became synonymous with multimedia authoring tools more broadly, enabled this paradoxically specific dedifferentiation, a vision of which was offered by McLuhan twenty-five years earlier: ‘It is as if a symphony composer, instead of sending his manuscript to the printer and thence to the conductor and to the individual members of the orchestra, were to compose directly on an electronic instrument that would render each note or theme as if on the appropriate instrument. This would end at once all the delegation and specialism of the symphony orchestra that makes it such a natural model of the mechanical and industrial age.’85 Put another way, sprawl is not a bug in, but rather a feature of both the postindustrial, multimedia age and the ‘end of history’: a moment in which a tightly controlled dialectics has seemingly relinquished the last vestiges of its grasp on both aesthetic and political processes.

In contrast to a system built on aesthetic oppositions, digital multimedia, founded on the structural opposition between one and zero, counterintuitively gives rise to a ‘formalism’ that encourages mishmash rather than polarity even as, at the same time, it nevertheless renders different types of media equivalent. This latter tendency can itself be found in Eisenstein’s early writings but, as Philip Rosen notes, with a material basis. For Rosen, multimedia

looks something like an off-center realization of Eisenstein’s idea that cinema could be organized around a common denominator shared by diverse sense impressions. Good materialist that he was, Eisenstein identified that common denominator as a physical phenomenon, but a quantifiable one—vibrations of air. In the digital utopia, however, the solution is to evacuate the physical and to find the common denominator in numbers as such, a universal coding procedure. 86

That this distinction is not simply related to multimedia but its political-economic counterpart is demonstrated by the fact that he is responding in part to Florian Rötzer’s invocation of both the ostensibly universal nature of digital encoding and ‘(t)he demise of the Berlin Wall’ as ‘the sign of a general fluctuation as prescribed by the ramified media networks’ heralding ‘a global society, prepared long ago by the capitalist system at the level of goods and capital flow.’87

The temporal implications of this shift are made clear in Cubase given how the timeline and arrangement views allow a musical piece to be reconfigured at whim. This supports what, for Théberge, is the way MIDI’s ‘“cut and paste” style of editing’ diminishes the fixed and linear nature of any given piece of music as ‘(t)he infinite maleability (sic) of the sequenced data mitigates against the idea of a single, finished product,’ and for which, as he notes of synthesizer patch editors, ‘the concept of “originality”…can sometimes appear virtually meaningless.’88 For Thrift, more computationally, ‘(t)here are no longer calculations with definite beginnings and ends. Rather there is a plane of endless calculation and recalculation, across which intensities continually build and fade.’89 Multimedia can thus be seen as kind of culmination and instrumentalization of postmodern aesthetics, as many, including Manovich, have noted.90

We can situate these developments conterminously with Maher’s timeline of multimedia’s accession. Mark Fisher—who, post-CCRU, became one of the foremost critics of neoliberal capitalism—would eventually argue that ‘(p)ostmodernism only achieved full-spectrum dominance after 1989, when “apparently victorious” capitalism thought itself in a position to declare the end of history.’91 For Fisher, ‘postmodernity could be defined as the succumbing of historical time to the spectral time of recording devices. Postmodern time presupposes ubiquitous recording technology, but postmodernity screens out the spectrality, naturalising the uncanniness of the recording apparatuses,’ to which he opposes what he and music critic Simon Reynolds came to call, after Jacques Derrida, hauntology: ‘When the present has given up on the future, we must listen for the relics of the future in the unactivated potentials of the past.’92 Yet it is increasingly apparent that this logic, so compelling in early 21st-century electronic music, ultimately cannot move beyond the durational precepts embodied since 1989 in Cubase. When everything is permutational, ‘we cannot produce new memories,’ even hauntologically.93

The Unbearable Length of Duration

In her consideration of the significance of minute temporal intervals to modernity, Jimena Canales’ initial discussion of Bergson’s debates with Albert Einstein in the first half of the twentieth century sheds some light on the way that the philosopher responded to modernist technologies of spatiotemporal discretization such as the micrometer and cinema.94 Canales argues that ‘Bergson exhorted his followers to peer into cinematographic black boxes to find real movement hidden there,’95 but, as we have seen with Goodman and Deleuze, most of their contemporary number have been content to locate such durational extensities in the effects, rather than the causes, of technological media. Indeed, this may even be true for Bergson himself, who, as is well known, once likened the brain to some of the most advanced technical—and sonic—media of his own time, ‘no more than a kind of central telephonic exchange.’96 By the advent of media theory proper in the 1960s, McLuhan would even see the universalizing promise of a Bergsonian consciousness-before-language in emerging digital technologies.97

For Canales, Bergson’s dispute with Einstein over the nature of temporality was given a larger context by their participation in a key League of Nations committee at whose head the former scholar sat, the International Commission for Intellectual Cooperation. ‘Discussions of time were particularly relevant’ there, she writes, ‘for one essential reason. Its organization was modeled after previous scientific international commissions created for global sciences…global industries…and global standards.’98 Bergson, ‘whose concept of durée,’ Friedberg writes, ‘was a rejection of ideas of absolute quantifiable time,’ was generally considered to have been unsuccessful there in defending his position against Einstein, who championed a relative yet utterly non-subjective time.99 The fall of the Berlin Wall, however, would provide an opportunity for Bergson’s ideas to not only assume the mantle of the dominant global temporality, but be celebrated for it, in Cubase and the multimedia timeline, by theorists and practitioners of the electronic dance music sweeping across the newly-reunified Europe and, subsequently, digital creators around the world. Yet this belated victory came only by stretching the core paradox of discrete durationality to its limit.

Indeed, there would appear to be something of a confluence between the late 1980s and this ideological unification of disparate elements, one whose time would appear to be running short today. The New York Times, for example, announced last year that it would no longer display television listings as a multi-tracked, rectangular grid, a format it introduced in early March 1988 to antinomically facilitate the traversal of what Raymond Williams famously described as that medium’s ‘flow’ via segmentation (although, being printed, readers of course had to provide their own timeline marker).100 Some, like Thrift, have embraced such contradictions, hoping that, rather than ‘less human because more “rational” and “flowsy”…(t)his background would enable new kinds of movement to occur, against which all kinds of experiments in perception might become possible, which might in turn engender new senses, new intelligences of the world and new forms of “human.”’101 But today, as post-Cold War edifices like the European Union find themselves under siege from rising worldwide nationalism, unifying conceptions of the timeline have been supplanted by the constantly updating font of disparate, asynchronous viewpoints that is the social media timeline, a construct over which users feel largely powerless. Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the term ‘doomscrolling,’ for what has become the macabre act of obsessively checking one’s feed, has gained popularity.102

These changes, which are not just developments but inversions, suggest, against Fukuyama, the persistence of a dialectic, one not ended but merely transferred, since the late 1980s until quite recently, from the realm of political economy into technology. It is therefore necessary to reconsider any notion of durée as the ultimate expression of technical mediation. If, as many over the past thirty years have done, we consider a binary digit as indivisible not in the holistic, analog sense that Bergson championed, but rather because it definitionally represents the minimal unit of division, the contradiction between Bergson and his media-theoretical successors seemingly disappears. But the paradoxical fantasy of a discrete, mediated plane of immanence, like that of a world unified under neoliberal capitalism, can only be sustained by this foundational disavowal. Unlike the universal metamedium that Bergson envisioned time and space to be, after three decades of channeling nearly all forms of expression through the remix machine of digital multimediation, we are faced today not with the unifying effects of its structure but the divisive consequences of its reign.

Author Biography

Andrew Lison is Assistant Professor of Media Study at The University at Buffalo, The State University of New York. His work has appeared in Configurations, Science Fiction Studies, and New Formations as well as a number of edited collections, including one of which he is co-editor, The Global Sixties in Sound and Vision: Media, Counterculture, Revolt (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014). He is also co-author of a volume, Archives, in the In Search of Media series (meson/University of Minnesota Press, 2019). Work on this article was supported by an Andrew W. Mellon Graduate Fellowship at Brown University and a Postdoctoral Researchship in the Digital Humanities at the Hall Center for the Humanities, University of Kansas.

Bibliography

Attali, Jacques. Noise: The Political Economy of Music (1977). Translated by Brian Massumi. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1985.

Bahr, Sarah. ‘A Final Episode for the TV Listings.’ The New York Times, August 28, 2020. Available online at https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/28/insider/TV-listings-ending.html accessed April 3, 2021.

Bergson, Henri. Matter and Memory (1896/1908). Translated by Nancy Margaret Paul and W. Scott Palmer. New York: Zone Books, 1988.

Bergson, Henri. Creative Evolution (1907). Translated by Arthur Mitchell. Mineola: Dover Publications, Inc., 1998.

Berk, Michael. ‘Technology: Analog Fetishes and Digital Futures.’ In Modulations–A History of Electronic Music: Throbbing Words on Sound, edited by Peter Shapiro. New York: Caipirinha Productions, 2000, 188–201.

Bolter, Jay David and Richard Grusin. Remediation: Understanding New Media. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999.

Brody, Florian. ‘The Medium is the Memory.’ In The Digital Dialectic, edited by Peter Lunenfeld. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1999, 134–49.

Brown, Timothy Scott and Andrew Lison. ‘Introduction.’ In The Global Sixties in Sound and Vision: Media, Counterculture, Revolt, edited by Timothy S. Brown and Andrew Lison. New York and Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014, 1–13.

Canales, Jimena. A Tenth of a Second: A History. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009.

Canales, Jimena. The Physicist and the Philosopher: Einstein, Bergson, and the Debate that Changed our Understanding of Time. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015.

Canter, Marc. ‘Marc’s Voice: 25th Anniversary of MusicWorks.’ Marc’s Voice, October 24, 2009. Archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20130430020441/http://marc.digitalcitymechanics.com/2009/10/24/25th-anniversary-of-musicworks/ accessed April 2, 2021.

Chun, Wendy Hui Kyong. Programmed Visions: Software and Memory. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2011.

Clover, Joshua. 1989: Bob Dylan Didn’t Have This to Sing About. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009.

Collins, Nick. ‘Electronica.’ In The Oxford Handbook of Computer Music, edited by Roger T. Dean. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009, 334–53.

Cramer, Florian. ‘Concepts, Notations, Software, Art.’ 2002. https://www.netzliteratur.net/cramer/concepts_notations_software_art.html accessed April 1, 2021.

Cusset, François. French Theory: How Foucault, Derrida, Deleuze, & Co. Transformed the Intellectual Life of the United States (2003). Translated by Jeff Fort with Josephine Berganza and Marlon Jones. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008.

Davis, Erik. ‘“Roots and Wires” Remix: Polyrhythmic Tricks and the Black Electronic’ (1995/2002). In Sound Unbound: Sampling Digital Music and Culture, edited by Paul D. Miller aka DJ Spooky that Subliminal Kid. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2008, 53–72.

Deleuze, Gilles. Cinema 1: The Movement-Image (1983). Translated by Hugh Tomlinson and Barbara Habberjam (1986). London: Continuum, 1992.

Deleuze, Gilles. Cinema 2: The Time-Image (1985). Translated by Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Galeta (1989). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010.

Derrida, Jacques. Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning and the New International (1993). Translated by Peggy Kamuf. New York: Routledge, 1994.

Eisenstein, Sergei. Film Form. Edited and translated by Jay Leyda. New York: Harcourt, 1949 (various pieces cited).

Eshun, Kodwo. More Brilliant than the Sun: Adventures in Sonic Fiction. London: Quartet, 1998.

Fisher, Mark. Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? Winchester: Zero Books, 2009.

Fisher, Mark. ‘The Metaphysics of Crackle: Afrofuturism and Hauntology.’ Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture 5:2 (2013): 42–55.

Fisher, Mark. Ghosts of My Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures. Winchester: Zero Books, 2014.

Friedberg, Anne. The Virtual Window: From Alberti to Microsoft. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006.

Fukuyama, Francis. ‘The End of History?’ The National Interest 16 (Summer 1989): 3–18.

Gay, Jonathan. ‘The History of Flash.’ Adobe.com date unknown. Archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20140821073137/https://www.adobe.com/macromedia/events/john_gay/ accessed April 1, 2021.

Goodman, Steve. ‘Timeline (sonic).’ In Software Studies: A Lexicon, edited by Matthew Fuller. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2008, 256–9.

Harvey, David. A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Kittler, Friedrich A. Gramophone, Film, Typewriter (1986). Translated by Geoffrey Winthrop-Young and Michael Wutz. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999.

Kleinermanns, Ralf. ‘“Welcome to the fair!” Die Frankfurter Musikmesse im Softwareüberblick.’ ST-Computer, March 1989: 63–6.

Laurel, Brenda. Computers as Theatre. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1991.

Levin, Thomas Y. ‘“Tones from out of Nowhere”: Rudolf Pfenninger and the Archaeology of Synthetic Sound’ (2002/2003). In New Media, Old Media: A History and Theory Reader, edited by Wendy Hui Kyong Chun and Thomas Keenan. New York: Routledge, 2006, 45–81.

Lévy, Pierre. Becoming Virtual: Reality in the Digital Age (1995). Translated by Robert Bononno. New York: Plenum, 1998.

Lison, Andrew. ‘Love’s Unlimited Orchestra: Overcoming Left Melancholy via Dubstep and Microhouse.’ New Formations 75 (Summer 2012): 122–39.

Lison, Andrew. ‘1968 and the Future of Information.’ In The Global Sixties in Sound and Vision: Media, Counterculture, Revolt, edited by Timothy S. Brown and Andrew Lison. New York and Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014, 245–74.

Lison, Andrew. ‘Toward a Theory of 100% Utilization.’ In Configurations 28:4 (Fall 2020): 491–519.

Lingoworkshop. ‘An Unofficial Brief History of Director.’ Lingoworkshop.com, March 21, 2005. Archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20170915060907/http://lingoworkshop.com/articles/history accessed April 2, 2021.

Malabou, Catherine. What Should We Do with Our Brain? (2004). Translated by Sebastian Rand. New York: Fordham University Press, 2008.

Manovich, Lev. ‘What Is Digital Cinema?’ In The Digital Dialectic, edited by Peter Lunenfeld. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1999, 172–92.

Manovich, Lev. The Language of New Media. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2001.

Manovich, Lev. ‘Inside Photoshop.’ Computational Culture 1 (November 2011) http://computationalculture.net/article/inside-photoshop accessed May 12, 2017.

Maher, Jimmy. The Future Was Here: The Commodore Amiga. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012.

McLuhan, Marshall. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (1964). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1994.

McLuhan, Marshall and Quentin Fiore. The Medium is the Massage: An Inventory of Effects (1967). Berkeley: Gingko Press, 2001.

Mitchell, W.J.T. Picture Theory: Essays on Verbal and Visual Representation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994.

Moog, Robert. ‘MIDI—What It Is and What It Means to Electronic Artists’ (1984). In Ars Electronica: Facing The Future, edited by Timothy Druckrey with Ars Electronica. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999, 66.

Nicholson, Dave. ‘Why is Cubase Called Cubase?’ Steinberg Forums, January 2012. https://forums.steinberg.net/t/why-is-cubase-called-cubase/611887/9 accessed April 1, 2021.

Reynolds, Simon. Energy Flash: A Journey Through Rave Music and Dance Culture (1998). Updated 20th anniversary edition. London: Picador, 2008.

Reynolds, Simon. ‘Renegade Academia: The Cybernetic Culture Research Unit.’ Unpublished director’s cut, 1999. Available online at https://energyflashbysimonreynolds.blogspot.com/2009/11/renegade-academia-cybernetic-culture.html accessed April 1, 2021.

Reynolds, Simon. Retromania: Pop Culture’s Addiction to its Own Past. New York: Faber and Faber, 2011.

Rosen, Philip. Change Mummified: Cinema, Historicity, Theory. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2001.

Rötzer, Florian. ‘Virtual Worlds: Fascination and Reactions.’ In Critical Issues in Electronic Media, edited by Simon Penny. Albany: SUNY Press, 1995, 119–31.

Rubin, Michael. Droidmaker: George Lucas and the Digital Revolution. Gainesville: Triad Publishing, 2006.

Schewe, Jeff. ‘10 Years of Photoshop: The Birth of a Killer Application.’ PEI, February 2000: 1–10. Available online at http://www.schewephoto.com/pei/pshistory.pdf accessed June 30, 2020.

Shannon, Claude E. and Warren Weaver. The Mathematical Theory of Communication (1948/1949). Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1998.

Skoller, Jeffrey. Shadows, Specters, Shards: Making History in Avant-Garde Film. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2005.

Snow, David. ‘Cubase: Pro-level MIDI Sequencer.’ STart 5:1 (August 1990). Archived at https://www.atarimagazines.com/startv5n1/cubase.html accessed September 14, 2019.

Terranova, Tiziana. Network Culture: Politics for the Information Age. London: Pluto Press, 2004.

Théberge, Paul. Any Sound You Can Imagine: Making Music/Consuming Technology. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 1997.

Thrift, Nigel. ‘Movement-space: The Changing Domain of Thinking Resulting from the Development of New Kinds of Spatial Awareness.’ Economy and Society 33:4 (November 2004): 582–604.

Thrift, Nigel and Shaun French. ‘The Automatic Production of Space.’ Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 27:3 (2002): 309–35.

Trask, Simon. ‘Theme and Variations: Frankfurt Musikmesse 1989.’ Music Technology, March 1989: 26–8.

Turner, Fred. From Counterculture to Cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the Rise of Digital Utopianism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006.

Tweak. ‘Pictures of Vintage MIDI Sequencers.’ Tweakheadz. https://tweakheadz.com/vintage_sequencers.html accessed April 1, 2021.

Watson, Allan. Cultural Production in and Beyond the Recording Studio. New York: Routledge, 2015.

Watercutter, Angela. ‘Doomscrolling Is Slowly Eroding Your Mental Health.’ WIRED, June 25, 2020. Available online at https://www.wired.com/story/stop-doomscrolling/ accessed July 18, 2020.

Waldron, Rick. ‘The Flash History.’ Flashmagazine.com, November 20, 2000. Archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20190722165129/http://www.flashmagazine.com/news/detail/the_flash_history/ accessed April 1, 2021.

White, Paul. ‘Karl Steinberg: Cubase & Computers’ (interview with Karl Steinberg). Sound on Sound,January 1995. Archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20150608005703/http://www.soundonsound.com/sos/1995_articles/jan95/karlsteinberg.html accessed May 13, 2017.

Wikipedia. ‘Steinberg Cubase (Versions).’ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Steinberg_Cubase#Versions accessed September 11, 2019.

Wikipedia user Dogman15. ‘MIDI sample.mid.’ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:MIDI_sample.mid accessed June 7, 2014.

Williams, Raymond. Television: Technology and Cultural Form (1974), second edition (1990). Edited by Ederyn Williams. London: Routledge Classics, 2003.

Notes

- Nick Collins, ‘Electronica’ in The Oxford Handbook of Computer Music, ed. Roger T. Dean (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 338. See also Allan Watson, Cultural Production in and Beyond the Recording Studio (New York: Routledge, 2015), 22. The Wikipedia page for Cubase, citing the latter, goes on to say ‘(t)his was much more intuitive and allowed much easier editing than the prior system of parameter lists. It has since been copied by just about every other similar product’ (‘Steinberg Cubase (Versions),’ Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Steinberg_Cubase#Versions accessed September 11, 2019; see also Tweak, ‘Pictures of Vintage MIDI Sequencers,’ Tweakheadz https://tweakheadz.com/vintage_sequencers.html accessed April 1, 2021). ↩

- Paul White, ‘Karl Steinberg: Cubase & Computers,’ Sound on Sound, January 1995 archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20150608005703/http://www.soundonsound.com/sos/1995_articles/jan95/karlsteinberg.html accessed May 13, 2017 (emphasis in original). ↩

- E.g., Steve Goodman, ‘Timeline (sonic),’ in Software Studies: A Lexicon, ed. Matthew Fuller (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2008), 256–9 and the treatment of Adobe Photoshop’s layers feature in Lev Manovich, ‘Inside Photoshop,’ Computational Culture 1 (November 2011) http://computationalculture.net/article/inside-photoshop accessed May 12, 2017 (both discussed further below). ↩

- See screenshots of CelAnimator and the discussion of the early history of Flash in Rick Waldron, ‘The Flash History,’ flashmagazine.com, November 20, 2000 archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20190722165129/http://www.flashmagazine.com/news/detail/the_flash_history/. For a history of Flash as told by one of its creators see Jonathan Gay, ‘The History of Flash,’ Adobe.com, date unknown archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20140821073137/https://www.adobe.com/macromedia/events/john_gay/ (both URLs accessed April 1, 2021). In the interest of full disclosure, I note that I worked at Macromedia, albeit not directly on any of its products, from 1996–1998 and again in 2000; while those experiences inform my perspective, my focus is on the historical period prior to my involvement, which was relatively minor and distinct from the company’s software. ↩

- Simon Trask, ‘Theme and Variations: Frankfurt Musikmesse 1989,’ Music Technology, March 1989: 26. On the history of the name, see Steinberg GUI Architect Dave Nicholson’s 2012 post on the official Steinberg forums at https://forums.steinberg.net/t/why-is-cubase-called-cubase/611887/9 accessed April 1, 2021. ↩

- Ibid.; Wendy Hui Kyong Chun, Programmed Visions: Software and Memory (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2011), 59–95. ↩

- Ibid., 59. On Harvey see ibid., 7, 74. ↩

- David Harvey, A Brief History of Neoliberalism (Oxford: Oxford University Press05), 12, 41–2, 13; Andrew Lison, ‘1968 and the Future of Information’ in The Global Sixties in Sound and Vision: Media, Counterculture, Revolt, eds. Timothy S. Brown and Andrew Lison (New York and Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), 262. ↩

- Harvey, A Brief History of Neoliberalism, 146, 159; Fred Turner, From Counterculture to Cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the Rise of Digital Utopianism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006). See also Lison, ‘1968 and the Future of Information.’ ↩

- Jimmy Maher, The Future Was Here: The Commodore Amiga (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012), 5 (emphases in original). On 1960s multimedia see also e.g., Anne Friedberg, The Virtual Window: From Alberti to Microsoft (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006), 205–15, Turner, From Counterculture to Cyberculture, Lison, ‘1968 and the Future of Information,’ and Timothy Scott Brown and Andrew Lison, ‘Introduction’ in Brown and Lison eds., The Global Sixties in Sound and Vision. ↩

- Francis Fukuyama, ‘The End of History?,’ The National Interest 16 (Summer 1989), 8. ↩