Introduction

Twitter is not only a platform for the circulation of all kinds of messages; it is simultaneously an interface that makes this very activity explicitly visible. It is a highly reflexive infrastructure, as it automatically produces dynamic accounts of its infrastructural activity. I assume that these accounts are in no way a secondary, ex-post addition or a neutral formalization of that activity but rather a defining condition thereof: Twitter’s infrastructural reflexivity is a key driver for both, its everyday practices and its history. In what follows, I will make an attempt to unfold a history of one crucial strand of Twitter’s development as a reflexive infrastructure: The stabilization of retweeting before the company Twitter introduced a retweet button in November 2009.

This history first tries to understand the popularization of distribution practices such as writing ‘RT @username’ at the beginning of a retweeted tweet: How is it possible, that unconnected, manual activities turn into a stable practice? From a praxeological perspective, this calls for an explanation as ‘practices are not only recurrent patterns of action (level of production) but also recurrent patterns of socially sustained action (production and reproduction).’ 1. I argue that central actors for the socialization of retweeting, i.e. rendering retweeting a collective practice, were apps, as they were able to formalize procedures on a medium scale. 2

Second, it will try to outline, how this has been turned into a unit called ‘the retweet’, i.e., a social medium that can be given, received, collected and counted. Unitization is thus understood as a special kind of formalization. A result of this unitization is that retweeting as an infrastructural activity is made reflexive. I will demonstrate that although it is possible to show how and by whom retweet counters were introduced before November 2009, it is impossible to assign this crucial step in Twitter’s history to a single ‘inventor’. Rather, it is precisely the quest for an inventor that makes evident, how the development of this social medium dissolves into a long ‘chain of translations,’ where transformation occurs, because old technologies and practices are translated into a new context. 3

Third this history of early retweeting has to be complicated further: These formalizations and unitizations are accompanied and yielded at the same time by their narrativization. Counters and their interfaces in apps and similar services did not only spread and stabilize technologies and practices of retweeting; they also spread a description of Twitter as a powerful circulation machine, one that includes many different voices and brings a participatory, always-counted crowd to the fore, a crowd that is supposed to be somewhat more heterarchical than the old media institutions. In other words, the history of the retweet is also a history of its own historiography, or rather, its ‘media biography’.4

This observation holds true for the descriptions and accounts produced by counters as well as for the media coverage of the social media platform. This coverage has contributed to the platform’s rise as a global infrastructure by displaying it as such: Twitter’s growth also rests upon spectacular, globally spread stories, whose core is their distribution activity, their countability and, often as a result, the presumably increasing power of individuals and the decline of institutions. I will start with a perspective on Twitter’s narrativization in early 2009, before the introduction of the retweet button was announced. This will not only show what powerful narratives about Twitter looked like and how they contributed to Twitter’s popularization. It will also demonstrate the inseparability of formalization, unitization and narrativization by outlining, through which formalizations retweets have become objects of the narrative.

Three Steps in the Narrativization of Twitter as an Infrastructure

One of the first events that serves as a popular example of Twitter as an infrastructure is the ‘Miracle on the Hudson’: the touch-down of U.S. Airways Flight 1549 on the Hudson River on January 15, 2009. Twitter user @jkrums posted a picture on Twitpic, displaying the water-landed A320 slowly sinking into the water with a group of densely gathered passengers standing on the airplane’s right wing. The picture was celebrated as an instance of ‘citizen journalism’5—the retrospectively somewhat utopian idea that ‘everybody’ might become a journalist thanks to the popularization of the internet, which gave everyone a means of distributing news. This event also prompted the question of what facilitated the spread of this image. Most articles only mention @jkrums’ 170 followers, a number that increased to 10.000 after the incident.6 It is clear that somehow, the images must have gone beyond @jkrum’s 170-follower circle quickly, as only 30 minutes after taking the photo, he was interviewed by MSNBC. 7 Many articles mention that people became aware of the image via practices that can be summarized as varieties of retweeting, such as ‘echoing’ or doing a ‘hat tip’8 Still, explanations of the ‘miracle’—which appeared not least as an infrastructural miracle—concern mostly only one other actor besides the follower count. The Los Angeles Times Technology Blog, for example, stated on the day of the incident: ‘In this case, it was possible through the iPhone, an all-in-one communications device that can capture and send images in no time’.9 The combination of mobile devices and follower counts forms a stable explanatory scheme in Twitter-coverage and accounts for much of the public fascination with the platform at that time, as it is concerned with the changing relation between individuals and mass media institutions and the presumed new instability of that relation. Retweeting however—although unquestionably important for the ‘miracle’—is not part of the explanatory scheme.

The fascination with the follower count becomes even more evident in a second crucial biographical passage two months later: the ‘One Million Follower Race’ between Ashton Kutcher and CNN in March 2009, an event that contributed more to Twitter’s growth than almost any other single event.10 Again, this race to determine who would be the first to reach the frontier of one million followers discursively negotiated the expected new power of individuals and the decline of institutions.

In a YouTube video produced the day before the end of the race, Kutcher explained his motives: ‘I think it is a huge statement about social media, that for one person to actually have the ability to broadcast to as many people as a major media network, I think sort of signifies the turning of the tide from traditional news outlets to social media outlets, social news outlets.’11 Kutcher argues that with these social media activities, ‘we’ became the source and broadcasters of the news12 and that the follower race showed social media to be ‘as powerful as the major news outlets. […] this is sort of power to the people’.13

Kutcher’s statement indicates that first, the follower count fosters the idea that in one single number, all the different actors and procedures producing ‘power’ can be measured and compared. Second, it suggests a need to negotiate this quantified power, resulting in the populist imaginary that a journalism produced by ‘the people’ would contribute to a somehow better society. Third, it is precisely this process of translating power into definite numbers, subjecting it to negotiation, that makes Twitter itself popular. The formalization of an audience into single accounts and their unitization into a follower count is the precondition of this narrative of a conflict.

This conflict however, is not new to digital media biographies. Rather, it is the translation of an old narrative into a new context: The notion that digitization would empower individuals over institutions and that this would lead to a better, more communalist and participatory society has a longer history that can be traced back at least to the 1960s.14 Translated into a regime of countability, however, these old ideas gain a different status, as they appear to become negotiable. The seemingly precise data convey the impression that they are able to ‘signif[y] the turning of the tide.’ That means, the fascination for Twitter is not so much driven by its ‘mere’ infrastructural activity, but rather by its infrastructural reflexivity, fostering a novel negotiability.

A third key event took place in June 2009, when, following the presidential election in Iran, the participatory narrative escalated to a point that forced media outlets to critically analyze their own overzealous coverage.15 Although criticized early on,16 the protests against the election process were not only celebrated as the ‘Green Revolution’ but especially as a ‘Twitter Revolution’. The public construction of Twitter as a news infrastructure, however, functioned slightly differently than in the two earlier events. TIME magazine asked: ‘So what exactly makes Twitter the medium of the moment?’17 The answer: It was ‘built to spread’ as ‘urgent tweets tend to get picked up and retransmitted by other twitterers, a practice known as retweeting, or just RT’.18 Here, communicative power is not displayed by the number of followers, but by the actual circulation of a tweet.

As an example, that article—which is quite critical about Twitter’s capacities because it also provided a useful way to monitor protesters—mentions a tweet that was ‘retweeted more than 200 times’.19 Thus, in June 2009, retweeting, rather than the follower count, becomes prominent. The focus shifts from powerful persons (with many followers) to powerful tweets (with many retweets), or, put differently, to a considerably increasing degree, tweets become mobile objects with a numerable and narratable trajectory. One result is that the English-speaking Wikipedia presents the ‘Green Revolution’ as the major driver of the establishment of retweeting: ‘In 2009, the ‘retweet’ phenomenon would experience a major uptick in adoption by Twitter users in order to forward SMS posts by Iranian observers and participants in the events following the Iranian presidential election’.20 The only other step in the history of retweeting the article names thereafter is that ‘In August 2009, Twitter officially began integrating the ‘retweet’ mechanism by replacing the string ‘RT @username’ with a retweet symbol emulating Tumblr’s reblog symbol’.21

I argue, first , that retweets became objects of media coverage during the ‘Green Revolution’, and not during the ‘One Million Follower Race’ or the ‘Miracle on the Hudson’, not because retweeting was somehow developed, stabilized and established in the meantime but because retweets had become countable units. Second, this countability has reinvigorated the participatory narrative whose history Fred Turner described as ‘new communalism’,22 as it rendered this notion publicly negotiable. Third, this narrative not only inscribed into events such as Ashton Kutcher’s ‘power to the people’ into popular accounts of Twitter but also into the scholarly distinction between technologies and practices, championing the idea of more powerful users and less powerful institutions.

Technologies and Practices?

Both, scholarly and popular publications on retweeting, emphasize two steps in the history of retweeting. The first is that retweeting and other features, such as the hashtag and the @reply, were a ‘user-lead innovation: Twitter users, not its engineers are ultimately responsible for a number of core features which are now in use by the Twitter community’23. Löwgren and Reimer state that ‘[…] both the hashtag and retweet function were designed by users rather than by original producers of Twitter’.24

Both positions are careful not to overly differentiate between users and engineers, practices and technologies; Löwgren and Reimer in constraining the latter half of the dichotomy to Twitter employees and Bruns by drawing on Eric von Hippel’s concept of the ‘user toolkit’, which marks a link between users and producers by providing means by which users can ‘channel innovative effort’. Bruns argues that Twitter’s APIs would work like a ‘user toolkit,’ as they facilitated third-party apps.25 As a result, the purported ‘innovation’ remains in a homogeneous group called ‘users’, encompassing both end users and app producers. Bruns does not overcome this dichotomy, rather, he shifts the boundaries, reintroducing it as a difference between ‘top-down innovation’ and the ‘bottom-up, user-developed innovation of manual retweeting’, which was disrupted by Twitter’s ‘failures to completely understand […] user innovation’.26

The second step: Beginning on November 6, 2009, Twitter rolled out its retweet button, which led to several transformations. With the manual RT @username practice, every retweet would be a copy of the text of another tweet. With the retweet button, retweeting a tweet meant retweeting an original—including profile pictures and without the possibility to edit the tweet.

More recent publications have begun to correct Twitter’s bottom-up image. Alexander Halavais, for example, stresses the coevolutionary character of Twitter’s technologies. He outlines Twitter’s prehistory in RSS and IRC and comments on the notion of user invention: ‘[T]here is a wrinkle in this story. In incorporating these changes, Twitter did more than merely make formal the informal workarounds of its users. These appropriations often displaced social practices that better represented the diversity of users and their needs, replacing them with model uses (and users) imagined’.27 Whether or not the old practices represented diversity better than the new ones, every formalization of a practice entails translation, and every translation entails transformation.

Consequently, Twitter’s update prompted very different reactions, among them a lot of emotional complaints, as for many users, this update was a radical breach of sociotechnical rules of privacy and intimacy. One of the most commented complaints is that of Lisa Barone, published on November 18., 2009 on outspokenmedia.com:

Itʼs jarring. To suddenly see someone you donʼt know in your sacred space. Thatʼs how I feel about the new Retweet Feature on Twitter. Not because Iʼm having a ‘Facebook moment’ where change freaks me out, but because they just ruined and violated some of the core ways people use Twitter. The ones users had created themselves.28

According to this popular complaint, the update produced a disruption of user practices. This disruption might be understood as an experience of strangeness, making latent social structures manifest29 or even a social breaching30 engendering moral indignation, as it breaks with the routine grounds of everyday activities: In the ethnomethodological tradition, breachings like these made it possible to focus ‘[…] on the phenomenological conditions of intersubjectivity and uncovered, with the help of the ‘breachings,’ the morally sanctionable ‘fait social’ of everyday interaction in them.’ 31. These phenomenological conditions were technical conditions here, disrupted by an update.

That means this case did not only make visible that the formalization of retweeting entailed a transformation of practices. It also showed how this transformation was implicitly moral, as the older software conditions constituted a ‘social fact’ in a Durkheimian sense, or, put differently, that translating an old media practice into a new one by formalization can bring media technology’s otherwise latent conditions of intersubjectivity to the fore, and, as a result, their implicit morality.

However, it is important not to forget, how Lisa Barone’s description must not be taken as a ‘neutral’ description of social realities, but as an account deeply rooted in older narratives (which at the same time reproduces and produces exactly these narratives): The breach wrote its own nostalgic history of untouched, wild user practices ‘created by themselves’, disturbed by a top-town implementation, forcing users to have strangers on their timelines for the first time instead of only manually copied tweets of strangers with avatars of their own selected followings.

As a result, several users started looking for the origins of these practices32 and found two tweets: One from @TDavid from January 8., 2008, which was the first to use the later-stabilized form RT@username,33 and another from @Ericrice from April 17., 2007, which was the first to use the form ‘ReTweet @username.’34 There are many similarly early tweets using other forms, such as the ‘echo’, or the ‘Retwitter’, which was actually the first form I found; it is a tweet by @extraface from February 8., 2007—a pun about twittering itself.35

The Stabilization of RT

The reproduction of the narrative of ‘original user practices’ thus yielded new narratives about the ‘invention’ of retweeting: The translation of retweeting practices motivated a quest for origins, where a differentiation was made between the ‘disturbing’ platform Twitter and ‘original’ once undisturbed user practices. Of course, the quest for the origins of retweeting is an infinite regress, it’s turtles all the way down, and, as we can already learn from Joseph Schumpeter’s Business Cycles, innovation has to be differentiated from invention. Innovation implies no creative claim, except for what Schumpeter calls ‘New Combinations’: ‘innovation combines factors in a new way, […] it consists in carrying out New Combinations’.36 This basic notion of technical, cultural or social change as a result of endless translations of translations, also has a tradition in cultural anthropology. For Marshal Sahlins for example, cultural change occurs through reproduction of old patterns in new contexts 37 Bruno Latour introduced this notion under the label of ‘translation’ as opposed to ‘diffusion’, where ‘everyone shapes [the circulating entity] according to their different projects.’ 38 Thus, the results of the chase for origins seem relevant, as the more one approaches the purported inventions, the more they dissolve into genealogies of earlier practices, technologies and narratives, and the more one is likely to observe the shaping and transformations some translations introduced into the process.

Some of these reported innovations are imported blogging practices, such as the ‘echo’, which gained a transformed meaning when practiced in the new context of the Twitter platform. Others were coproduced by the technical standards of the platform: The first Tweets to use the later-stabilized short version ‘RT @username’ used all 140 available characters or came very close to doing so.39 Thus, the shorthand versions were not a more-or-less intentional invention of single users, rather, they can be considered a result of the technical ‘top-down’ fact that the number of characters was limited. This situation changed in April 2008, when the shorthand version can be found more and more frequently, also far below the 140-character limit.40

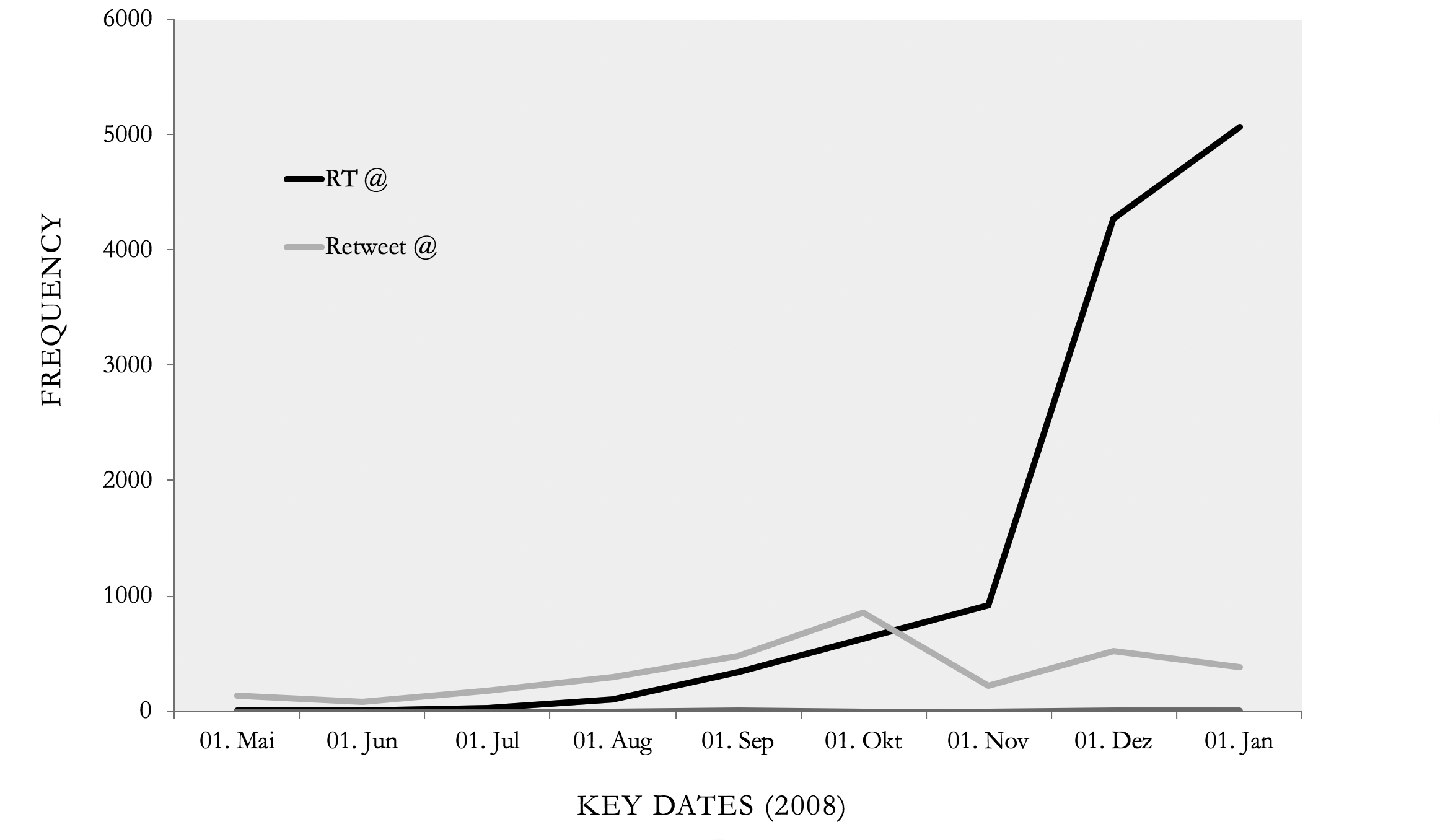

In spring 2008, a whole array of different retweet formats prevailed. As the most frequent among them appeared to be ‘ReTweet @username’ and ‘RT @username’, I tried to figure out how this ‘interpretative flexibility’41 came to such a state of ‘closure’42 that only the shorthand version stabilized on a global level, with the result that by 2009, many observers assumed that it had somehow been developed by a group of actors assumed to be ‘users’. A very rough method already brought significant results: Using Twitter’s search function, I counted how many times the string ‘Retweet @’ and ‘RT @’ appeared in the public Twitter archive on the first day of each month in 2008. The result is displayed in Figure 1: Both forms gained enough popularity to be measured by this method after April 2008—a finding that is supported by my personal impression scrolling through the archives. During April and May, many different ways of sharing tweets appear, and this trend generally increases for both forms until the end of summer. Until then, the longer, self-explaining version ‘Retweet’ is more prevalent than the later standard version ‘RT’. This ratio changes from one key date to the other: ‘RT’ overtakes ‘Retweet’, and then, on a later key date, ‘RT’ rises exponentially, and keeps rising, but nowhere near as steeply as around November 1.

Two issues seem worth explaining: First, consider when the long and the short versions change positions from one date to the other; looking in greater detail before the key date, I found this changed shortly after October 1. Second, it seems relevant that the shorthand version rises at the beginning of November from ca. 1.000 retweets per day to 5.000, and it stabilizes from that point onwards. Moreover, it appears noteworthy that both of these changes happened before the ‘Hudson Miracle’ and before the ‘One Million Follower Race’—which led to a much higher increase in users than whatever happened in November 200843— and well before the ‘Green Revolution’, which is supposed to mark the major uptick in retweeting. The figure shows that from November 2008 onwards, retweeting is an established procedure with one dominant form: ‘RT @username.’

Of course, this does not mean that the practice stabilized semantically. Even in July 2009, one can find tweets stating some users were going too far with ‘these retweets’. ‘USE UR OWN THOUGHTS.. ITS CALLED TWITTER NOT RETWITTER.’44 Rather, throughout 2009, one can observe how the meaning of Twitter changed gradually from an accumulation of ‘micro blogs,’ each publishing its own content, to an infrastructure of content circulation, mainly for news, opinions, and jokes. This change might at least partially be explained by what formally stabilized the retweet: the exponential increase of the shorthand version occurs exactly at November 4, the day of the American presidential election of 2008. The stabilization of the shorthand form must have been accomplished as it became usual during the electoral campaign, and especially on the day of the election. This seems plausible as first, in electoral campaigns, keeping enough space for somebody else’s message appears more important than producing ‘own thoughts’ and second, on the election day, a lot of spreadworthy news are being produced, such as calls for vote, exit polls, or results.

However, it seems noteworthy here that the establishment of retweeting was not a revolution, it was not a result of the export of western technology to the orient; rather, it occurred during what was perhaps the biggest mass media event in the world, organizing the most powerful state. In that context, the rise of the retweet looks not so much like a participatory practice, one that developed as a ‘bottom-up’ strategy of single persons against institutions, of dissidents against tyrants. Rather, the retweet’s upscaling emerged out of a coalition of old practices of American elections and the conditions of those new social media platforms. To circulate given messages, that are not ‘ur own thoughts’ but still appear to be worth spreading, was, as also seen on Tumblr with its reblog function, a rather uncommon practice for (micro)blogging. For electoral campaigning however, it had been common for centuries. It appears that these translations of practices of elections and blogging formed a new coalition that set the standards for Twitter.

Although, as Latour mentions above, ‘everyone’ shapes these kinds of translations according to their projects, some translations appear to be way more powerful than other ones. Whether an American electoral campaign starts retweeting in a shorthand manner or, for example, a Belgian, whether it is a traditional mass media event or a spontaneous protest, makes a huge difference. Thus, similar to other new media histories, such as that of Anonymous 45, also the history of the retweet appears deeply connected to ‘old’ media practices in a ‘hybrid media system’ manner 46

This observation, however, does not fully explain what happened at the end of September 2008. Of course, with regard to the distribution of political messages, the short hand version of retweeting seems more helpful, as it leaves more space for the original message. Nevertheless, this does not answer why the RT-curve rises and the retweet-curve falls at the same time. In addition, and most importantly, it does not explain why all those different forms, such as the use of dots, space signs or other slight changes, melted into two main standardized forms. How can a manual practice become standardized in a group of so many heterogeneous people?

The answer is strikingly simple: It is a myth that retweeting was only a manual practice until Twitter introduced a retweet button in November 2009. There were retweet buttons before Twitter’s alleged ‘top-down innovation’, disrupting the ‘naturally’ developed user practices: There were no ‘bottom-up’ stabilized manual practices, inscribing into technology. Rather, manual and automated retweeting practices have a longer prehistory of mutual stabilization, or, one might also say: of co-evolution. In September 2008, when the RT-curve crosses the retweet-curve, automated forms of retweeting were already so common that the update of a then-very-popular Twitter app resulted in the sudden decline of the longer, self-explaining form and the rise of the from-then-on stable shorthand version.

On December 21., 2007, i.e., even before @TDavid wrote the first tweet in the later stable ‘RT @username’ form, the app Twhirl, programmed by Marco Kaiser from the village Appen in northern Germany, announced in a Tweet: ‘rolled out new release 0.4.004. many bugfixes under the hood, don’t-ask-again option for delete confirmations, retweet button’.47

In 2008, Twhirl was among the most used Twitter apps. Technology blog readwrite.com celebrated it in May 2008 as the most popular Twitter app ‘according to the blogosphere’.48 Its retweet button looked similar to the ‘forward’ buttons in e-mail clients, and it actually functioned similarly to mail forwarding (another translation of an old media practice into a new one): A click on the button automatically copied a selected tweet and added a retweet form such as ‘Retweeting @username’ in front of the tweet one wanted to forward, or rather, to retweet. Thus, it functioned somewhat half-automatically with a default-set form. It is hard to say what the default version was. App reviews show that in July 2008, it might have been ‘Retweeting @,’ and in November 2008, a review shows ‘RT @’, but in any case, it was possible to change the format.49 Either way, most important here is that this early retweet button fastened manual retweeting, determining—as long as users do not change the form in their preferences tab—a constant form of retweeting for each user.

In July 2008, however, a Twitter app was launched, developed by Iain and Alison Dodsworth from Crowborough, East Sussex, and it would soon become the most popular Twitter app;50 so popular that Twitter bought it in 2011: TweetDeck had a built-in retweet button that functioned similarly to that of Twhirl, with the important difference that the retweet format was unchangeably preset by default—first in the version ‘Retweet @’. Then, in the late evening of September 26, 2008, TweetDeck conducted a poll over polldaddy.com, asking whether they should change the automatically inserted retweet form from ‘Retweet @’ to ‘RT @’.51A total of 70 persons participated, 15 voted ‘no’, 55 ‘yes’. An hour later, the app announced that the community had decided and they would change the retweet form to ‘RT’ in the next version, meaning that compared to Twhirl, TweetDeck fastened the formalization of retweeting further: Whereas Twhirl users (and earlier TweetDeck users) had to formalize their way of retweeting manually, the updated version of TweetDeck pre-determined this procedure by default. Very quickly thereafter, the ‘Retweet @’ curve in figure 1 fell and the ‘RT @’ curve started rising. So, was this a top-down or a bottom-up innovation?

The differentiation between ‘top-down’ and ‘bottom-up’, between ‘platform’ and ‘users’ or ‘technologies’ and ‘practices’ is simply not helpful if one wants to understand how retweeting developed and stabilized. It is as useful here as that between the ‘material’ and the ‘social’ criticized by Bruno Latour: “To distinguish a priori ‘material’ and ‘social’ ties before linking them together again makes about as much sense as to account for a dynamic of a battle by imagining a group of soldiers and officers stark naked with a huge heap of paraphernalia—tanks, rifles, paperwork, uniforms—and then claim that ‘of course there exist[s] some (dialectical) relation between the two’’.52 Rather than wondering how one can explain a media history drawing on these dichotomies, we should ask how this dichotomy is operationalized by whom. What is made visible by ‘the two’ and what is invisibilized? We will return to that later, but the important point for the retweet button is: If all those different producers of the retweet button are black-boxed as a large group called ‘users’, nobody can claim intellectual property rights, as it is everybody’s intellectual property.

What does become visible beyond these a priori differences, however, are several small translations that do not run from ‘technology’ to ‘practice’ and back again but are so inextricably intertwined, one being the precondition of the other and vice versa, that all we can describe are long chains of translations, resulting in transformations through context changes 53, for example, from e-mail clients or from blogging to a social media platform.

One of the most important translations happened when several, quite different manual procedures of retweeting were translated into Twhirl’s half-automated button, as that meant the next repetition would be an automatized reproduction of what previously had to be repeated manually. Manual repetition means there is a high probability of repetition that slightly differs every time. If this manual procedure is semiautomation, this facilitates the production of many different objects of a very similar shape. With half-automation, these similar objects appear in such a density that participants observe different examples of the same practice: Retweeting becomes something one does—not simply because a manual practice spreads but rather because a formerly manual practice is translated into a ‘durable’ material, or at least codified, form. The two steps of formalization, introduced by Twhirl (in a still very flexible manner) and TweetDeck (which closed possibilities to change retweet formats) both made retweeting less mutable and considerably more mobile. As a result, the practice becomes socially shareable and sustainable on a way larger scale; the same procedure can be performed by many different participants. This upscalability of usage practices follows a similar logic as the one Latour describes in his chapter ‘on immutable mobiles’ for the history of the printing press:

Anything that will accelerate the mobility of the traces that a location may obtain about another place, or anything that will allow these traces to move without transformation from one place to another, will be favored […]. The privilege of the printing press comes from its ability to help many innovations to act at once, but it is only one innovation among the many that help to answer this simplest of all questions: how to dominate on a large scale? 54

When retweets become increasingly more mobile and less mutable, this sets a standard for retweeting not only as something one does, but also as something one can do right; retweets look more like objects which normally have a certain form—a form that has especially been introduced by the semi-automation of retweeting through apps. Nevertheless, retweets cannot yet be considered a unit, as first they must be countable. Therefore, how did retweets become countable?

From Retweeting to Retweets

Again, this innovation was not implemented from Twitter when it introduced its retweet button in November 2009. Rather, it was part of an earlier translation from blogging into the new context of Twitter, before the ‘Green Revolution’ in Iran when TIME addressed retweets in its coverage. The most important service here was Tweetmeme, founded by Nick Halstead from London, who had earlier developed the service fav.or.it—a blog-aggregating platform that was considered a competitor to Digg: Tech Crunch even asked whether it was a ‘Digg killer’.55 Tech Crunch mentioned Tweetmeme for the first time in July 2008, saying it should act like Techmeme, a news aggregator for tech news, but for Twitter.56 Its core service was ‘indicating just how many people are re-tweeting popular links’.57 This step seems quite innovative, as probably for the first time, retweets are counted and rendered a measure of success online. However, ultimately, it was a quite simple translation of the presumed Digg killer fav.or.it into the context of retweets. In July 2008, when TweetDeck had been launched, and slightly more than half a year after Twhirl had introduced its retweet button, retweets were obviously solidified enough to be counted. The most important build-up had therefore been done by blog aggregators such as Digg, which had counted links from blog articles (instead of links from tweets) much earlier.

After that first mention of Tweetmeme in July 2008, things went silent around the service for a relatively long time. The first article thereafter is from May 1, 2009 and it criticizes Tweetmeme’s role in the case of a hoax about swine flu that looked like a BBC article and was recommended unverified by ‘crowdsourced news’. The article comments: ‘Tweetmeme encourages retweets with a big ‘re-tweeet this button’ [sic!] hence why it has now been re-tweeted 542 times, at last count’.58

Technically, Tweetmeme’s retweet button worked like Twhirl’s and TweetDeck’s half-automated buttons: It copied a tweet and added ‘RT @username’ (and earlier ‘via @tweetmeme’ was also added at the end of the tweet—which was problematic, for obvious reasons). The crucial difference between Tweetmeme’s and Twhirl’s retweet button is that the latter appears in the timeline of a user. Tweetmeme’s button, in contrast, does not appear in a timeline but in a ranking of already much-retweeted links. The button produces popularity on the basis of popularity—for articles linked on Twitter. This self-amplifying effect is a product of the retweet counter and marks a fundamental shift for twitter as a circulation infrastructure. This principle was again deemed helpful for another election campaign and was in turn further popularized through the campaign itself: The article on Tweetmeme’s button closes with the remark: ‘Meanwhile Tweetmeme’s influence is spreading. Its re-tweet button is now on the official web site for the Governor of California, Arnold Schwarzenegger’.59

This article was published less than a month after Tweetmeme had announced the launch of its button via its developers’ blog.60 The button and its measure for Twitter’s scope of links were so stunningly successful that as early as May 5, 2009, an article by tech journalist Erick Schonfeld was titled ‘Tweetmeme is Getting Freakin’ Awesome’. 61 From one month to the next, Tweetmeme’s number of unique visitors had grown from 26.000 to 385.000. Then, one month after Schonfeld’s article reported the success of counting retweets, the ‘Green Revolution’ began and the retweet became an object of global news coverage.

The Tech Crunch article then analyzed Tweetmeme’s design by comparing it to that of Digg—arguing that Tweetmeme had built almost everything similarly to Digg, except for the color: They replaced Digg’s orange with green, which remains the color of Twitter’s retweet button.62 One might wonder whether the retweet button was so successful not because it was such a great idea but rather because its increments of innovation63 were so microscopically small that it did not engender a social breach. The whole Twitter- and blogging ecosystem was ready to use the retweet button’s counter and ranking, and able to push it so intuitively, that the button and Tweetmeme’s metrics were not experienced as a stranger—quite the opposite, the Twitter- and blogging ecosystem had been prepared for so long for these kinds of techniques (by Digg and many others) that it seemed almost a ‘natural’ activity.

Some years later, in November 2012, Tweetmeme founder Nick Halstead told his version of what happened thereafter in an interview headlined ‘Meet the man who invented the re-tweet button.’ 64 In this interview, Halstead says that Tweetmeme ‘partnered with Twitter in the very early stages to show the most popular content shared on this social network’65 and explains this partnership in relation to Tweetmeme’s massive growth in popularity: ‘We also introduced the original retweet button used by news organizations and other 400,000 websites to promote their stories. Seeing the success of it, Twitter partnered with us and integrated the retweet button into their platform. Out of this partnership came a really close collaboration with Twitter’.66 Whatever this partnership looked like, Tweetmeme had become so successful with the counting of retweets that Twitter cooperated with the man who identifies himself as the inventor of the retweet button.

In July 2009, Erick Schonfeld published another article on Tweetmeme in which he prognosticated that retweets ‘are becoming the new currency of the web’.67 The button drove much of Twitter’s overall traffic, according to Halstead, and Tweetmeme was generating 196 million impressions per week. Thus, through Tweetmeme’s retweet button and its counter, retweets became so unified that they came to be considered something one can give and receive.68

Again, a month later, Twitter itself entered the retweeting scene. In a post on their corporate blog from August 13, 2009, titled ‘Project Retweet: Phase One,’ co-founder Biz Stone writes: ‘Some of Twitterʼs best features are emergent—people inventing simple but creative ways to share, discover, and communicate. One such convention is retweeting’.69 This statement was not only made in the weeks when ‘the man who invented the retweet button’ became so breathtakingly successful that his retweet function might have become a threat to Twitter, it is also the first instance I have found in which somebody claims the retweet was a user invention.

When Stone explains how retweeting works, he does not mention any of the different technologies of retweeting—technologies that had already been available for more than one-and-a-half years: ‘When you want to call more attention to a particular tweet, you copy/paste it as your own, reference the original author with an @mention, and finally, indicate that itʼs a retweet’.70 We do not know whether this was intentional or not. However, either way, Twitter had good reasons for following a double strategy: the company sought to partner with a dangerously successful man loudly identifying himself as the inventor of the retweet button (and who, in those very months, filed a successful lawsuit against retweet.com for plagiarizing Tweetmeme),71 and at the same time, it blurred the complicated innovation history of the retweet button by attributing it to an anonymous crowd of ‘users’, which has, in contrast to Nick Halstead, Iain Dodsworth and Marco Kaiser, no intellectual property rights. This strategy worked very well—so well indeed that at least to a certain degree, even scholarly publications repeated this corporate narrative.

Twitter’s narrative of a neutral translation of user practices into technology is contested by most publications. However, the politically more relevant dichotomy between ‘users’ and ‘platform’ generally remains uncontested. Alexander Halavais concludes that ‘it seems clear that Twitter responded to emergent retweet practices within the community with @replies, it seems clear that the platform-level solution to the problem only partially reflected the intentions and desires of a diverse user community’.72 Whereas Halavais acknowledges the transformative character of formalization, he sticks to the differentiation between a platform and a ‘community’ with given ‘desires’. Basically everybody who is not a Twitter employee falls into this category of a ‘community’, and all the differences within this community, from end users to startup managers, from apps to satellite platforms, from Lisa Barone to Nick Halstead, are black-boxed.

The result of black-boxing by sorting a whole network of heterogenous actors into the two categories of a dichotomy is that the complicated innovation history can be used for almost any narrative, as almost nobody knows how the innovation developed and where it came from. As a result, innovations can be attributed to anybody—for example, a ‘crowd’, a ‘community’ or ‘users’ without intellectual property rights and without ambitions for lawsuits.

Conclusion

Even though the retweet has no inventors, neither on an individual nor on a collective level (by ‘users’ or a ‘community’), but was rather established by long chains of translation, transforming the translated gradually, this article named mainly three actors whose translations made a considerable difference.

The first actor can be called—in absence of a better term—‘old media.’ Whereas events such as the ‘miracle on the Hudson’ or the ‘one million follower race’ were important for Twitter as a whole, the coverage of the presidential election in Iran 2009 and the campaigning for the presidential election in America 2008 were important for the retweet specifically. During the US-elections, retweeting as a practice to share Tweets was upscaled to a quantity that stabilized the shorthand version as a common routine. The coverage of the events around the Iranian election addressed retweeting explicitly as a phenomenon, popularizing Twitter and retweeting further. Thus, we can conclude that what the role of ‘old’ media and their established practices concerns, the retweet did not establish in an exclusive online realm. Rather, this functioned very much as previous research demonstrated for other assumed ‘internet phenomena’ as a cooperation between ‘new’ and ‘old’ media 73.

Second this cooperation was especially triggered by Twitter’s infrastructural reflexivity: Only after retweets had become counted, they were subject of mass media coverage—although in practice, they had been centrally important way earlier. These counters did not only make Twitters distribution activities easier describable, they also reinvigorated the old participatory narrative of digital media as communalist technology.

Third, it was crucial that retweeting never spread as a loose, manual practice, rather, formalization via semi-automation and manual retweeting mutually stabilized each other from the very beginning. This early automation functioned neither in a top-down, nor in a bottom-up manner. Its fastening of procedures that users typed manually into the app’s preferences tab was anything but neutral. It ‘fixed’ retweeting; objectifying it further in a first step largely into two interpretatively flexible forms (ReTweeting @ and RT@). In a second step, this interpretative flexibility was to large parts ‘closed’ into one form by TweetDeck and then upscaled during the US-election. In a third step, it was unitized through a translation from blog aggregation practices and technologies to Twitter.

Twitter’s essential addition to the media-practices of retweeting, however, was to render the retweeted tweet an original: From now on, it was one tweet that circulated through the internet, one original, instead of mostly second- or third-hand copies of an original. As a result, Tweets became single entities capable of travelling through the platform’s infrastructure and beyond, on news websites, blogs or messengers services. Whereas old media, semi-automation and counting made retweets constantly less mutable and more mobile, the company Twitter itself turned Tweets finally into immutable and mobile objects, having not only a fixed form, but also an infrastructure, they can circulate in. This however, was only one more step in a longer history of formalization, that has especially been driven by third party apps. As a result, at least in this case, apps appear not only as profiteers of and objects in infrastructures, but also as their co-producers.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback, Lisa Gerzen, Alexander Buhmann and Cornelius Schubert for helpful comments, and the special issue editors Carolin Gerlitz, Anne Helmond, David Nieborg, and Fernando van der Vlist for their elaborate suggestions, cooperative support and professional organization.

Bibliography

Barone, Lisa. “Why Twitterʼs New Retweet Feature Sucks.” Outspoken Media. November 18, 2009. http://outspokenmedia.com/social-media/twitters-new-retweet-feature-sucks/.

Bijker, Wiebe, Thomas Hughes, and Trevor Pinch (eds.). The Social Construction of Technological Systems. New Directions in the Sociology and History of Technology. Cambridge, MA/London: MIT Press, 2012 [1987].

Bruns, Axel. “Ad hoc innovation by users of social networks: the case of Twitter.” In ZSI Discussion Papers, ed. Centre for Social Innovation, 2012, https://eprints.qut.edu.au/49824/, 1–13.

Bunz, Mercedes. “Has Twitter reached its peak?” The Guardian. March 12, 2010. https://www.theguardian.com/media/pda/2010/mar/12/twitter-growth.

Butcher, Mike. “Is Favorit a Digg killer?” Tech Crunch. October 1, 2007. http://techcrunch.com/2007/10/01/is-favorit-a-digg-killer/.

———. “Tweetmeme takes another bite at ranking Twitter links.” Tech Crunch. July 21, 2008. http://techcrunch.com/2008/07/21/tweetmeme-takes-another-bite-at-ranking-twitterlinks/.

———. “Tweetmeme lets hoax ‘Zombie Swine Flu’ BBC story go-unchecked.” Tech Crunch. May 1, 2009. http://techcrunch.com/2009/05/01/london-is-not-quarantined-byzombie-swine-flu-yet-tweetmeme-lets-hoax-bbc-story-go-unchecked/.

Chadwick, Andrew. The Hybrid Media System: Politics and Power. 2nd ed., Oxford: OuP, 2017.

Collins, Harry M. “The Sociology of Scientific Knowledge: Studies of Contemporary Science.” Annual Review of Sociology 9, (1983): 265–285.

Frommer, Dan. “U.S. Airways Crash Rescue Picture: Citizen Journalism, Twitter At Work.” Business Insider. January 15, 2009. https://www.businessinsider.com/2009/1/us-airways-crash-rescue-picture-citizen-jouralism-twitter-at-work?IR=T.

Garfinkel, Harold. Studies in Ethnomethodology. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 2013 [1967].

Gherardi, Silvia. “Practice? It’s a Matter of Taste!” Management Learning 40, no. 5 (2009): 535–550. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350507609340812.

Grossman, Lev. “Iran Protests: Twitter, the Medium of the Movement.” TIME. June 17, 2009. http://content.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,1905125,00.html.

Halavais, Alexander. “Structure of Twitter: Social and Technical.” In Twitter and Society, eds. Katrin Weller, Axel Bruns, Jean Burgess, Merja Mahrt, and Cornelius Puschmann, 29–42. New York: Peter Lang, 2014.

Kutcher, Ashton. “Update from Ashton Kutcher about Twitter challenge.” April 15, 2009. https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=164&v=ma8AcfKGaEI.

Latour, Bruno. “The Powers of Association.” The Sociological Review 32, no. 1_suppl (1984): 264–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.1984.tb00115.x.

———. “Drawing Things Together,” in Michael Lynch and Steve Woolgar, eds. Representation of Scientific Practice. Cambridge/MA: MIT Press, 19–68.

———. Reassembling the Social. An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Löwgren, Jonas and Bo Reimer. Collaborative Media: Production, Consumption, and Design Interventions. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013.

Morozov, Evgeny. “Iran Elections: A Twitter Revolution?” Washington Post. June 17, 2009. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/discussion/2009/06/17/DI2009061702232.html??noredirect=on.

Natale, Simone. “Unveiling the biographies of media: On the role of narratives, anecdotes and storytelling in the construction of new media’s histories.” Communication Theory 26, no. 4 (2016): 431–449.

Nelson, Richard R. and Sidney G. Winter. An evolutionary theory of economic change. Cambridge, Belknap Press, 1982. Accessed October 7, 2018. http://readwrite.com/2009/08/21/retweetcom_is_no_competition_for_tweetmeme.

N.N. “The Most Popular Twitter Apps According to the Blogosphere.” Readwrite. May 16, 2008. http://readwrite.com/2008/05/16/most_popular_twitter_apps_blogosphere.

———. “Who first used the term ‘RT’ on Twitter?” Quora, N.D., https://www.quora.com/Who-first-used-the-term-RT-on-Twitter.

Paßmann, Johannes, and Carolin Gerlitz. “’Good’ Platform-political reasons for ‘bad’ platform-data. Zur sozio-technischen Geschichte der Plattformaktivitäten Fav, Retweet und Like.” Mediale Kontrolle Unter Beobachtung 3, no. 1 (2014): 1–40.

Paßmann, Johannes. Die soziale Logik des Likes. Eine Twitter-Ethnografie. Frankfurt a.M./New York: Campus, 2018.

Perez, Sarah. “Retweet.com Is No Competition for Tweetmeme.” Readwrite. August 21, 2009. http://readwrite.com/2009/08/21/retweetcom_is_no_competition_for_tweetmeme.

Phillips, Whitney. This is why we canʼt have nice things. Mapping the relationship between online trolling and mainstream culture. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2015.

Rechis, Leland. “Twitter for Android: Robots like to share too.” April 30, 2010. https://blog.twitter.com/official/en_us/a/2010/twitter-for-android-robots-like-to-share-too.html

Sahlins, Marshall. “Culture and Environment.” In: Sol Tax, ed., Horizons of Anthropology. Chicago: Aldine, 1964, 132–147.

———. Historical Metaphors and Mythical Realities. Structure in the Early History of the Sandwich Islands Kingdom. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1981.

Sarno, David. “Citizen photo of Hudson River plane crash shows Web’s reporting power.” L.A. Times Blog. January 15, 2009. http://latimesblogs.latimes.com/technology/2009/01/citizen-photo-o.html#sthash.4Io2XDFY.dpuf.

Schonfeld, Erick. “Tweetmeme Is Getting Freakinʼ Awesome.” Tech Crunch. May 5, 2009. http://techcrunch.com/2009/05/05/tweetmeme-is-getting-freakin-awesome/.

———. “Tweetmeme Wants To Be The King Of Retweets.” Tech Crunch. July 3, 2009. https://techcrunch.com/2009/07/03/tweetmeme-wants-to-be-the-king-of-retweets/.

Schroeder, Stan. “How Twitter Conquered the World in 2009.” Mashable. December 25, 2009. https://mashable.com/2009/12/25/twitter-2009/?europe=true.

Schumpeter, Joseph A. Business Cycles. A Theoretical, Historical and Statistical Analysis of the Capitalist Process. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1939.

Schüttpelz, Erhard. “From Documentary Meaning to Documentary Method: A Preliminary Comment on the Third Chapter of Harold Garfinkel’s Studies in Ethnomethodology.” Human Studies, accepted for publication (2019), https://doi.org/10.1007/s10746-019-09512-8.

Schütz, Alfred. “The Stranger: An Essay in Social Psychology.” American Journal of Sociology 49, no. 6 (1944): 499–507.

Stone, Biz. “Project Retweet: Phase One.” blog.twitter.com. August 13, 2009. https://blog.twitter.com/2009/project-retweet-phase-one.

Sysomos. “Inside Twitter: An In-Depth Look Inside the Twitter World.” June, 2009. http://www.sysomos.com/inside-twitter.

Tripathi Chopra, Shruti. “Meet the man who invented the re-tweet button.” London Loves Business. November 26, 2012. http://www.londonlovesbusiness.com/entrepreneurs/fast-growingbusinesses-and-sme/meet-the-man-who-invented-the-re-tweetbutton/4002.article.

Turner, Fred. From Counterculture to Cyberculture. Steward Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the Rise of Digital Utopianism. The University of Chicago Press: Chicago/London, 2006.

TweetDeck. “Is it ok to change ‘Retweet’ to ‘RT’ when clicking on the Retweet button?” Polldaddy.com. September 26, 2008. https://polldaddy.com/poll/953156/.

Tweetmeme. “Major Revamp Part 2.” blog.tweetmeme.com. February 18, 2009. https://web.archive.org/web/20100527015111/http://blog.tweetmeme.com/2009/02/18/major-revamp-part-2/.

Weaver, Matthew. “Iran’s ‘Twitter revolution’ was exaggerated, says editor.” The Guardian. June 9, 2010. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2010/jun/09/iran-twitter-revolution-protests.

Wikipedia. “Reblogging.” Accessed October 7, 2018. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reblogging.

Williams, Evan. “Twitter for iPhone.” April 10, 2010. https://blog.twitter.com/official/en_us/a/2010/twitter-for-iphone-1.html

Zdanowicz, Christina. “‘Miracle on the Hudson’ Twitpic changed his life.” CNN.com. January 15, 2014. https://edition.cnn.com/2014/01/15/tech/hudson-landing-twitpic-krums/index.html.

Author Biography

Johannes Paßmann is research associate of the Digital Media & Methods team at Siegen University. He obtained his doctorate in 2016 with a thesis on Twitter in Germany. Johannes was a research fellow at Locating Media, a postgraduate program funded by the German Research Foundation, worked as a lecturer in the Department of Media & Culture Studies at Utrecht University, and was visiting researcher at the Nordic Centre for Internet & Society (Oslo). His research focuses primarily on the sociology, history, and aesthetics of social media.

Notes

- Gherardi, “Practice? It’s a Matter of Taste!” ↩

- It is important to note that these apps were all third party applications and that Twitter started introducing its own apps after all what is described below: on April 10, 2010, they announced the acquisition of “Tweetie”, which they renamed into “Twitter for iPhone” (Williams, “Twitter for iPhone”), on April 30, 2010, they introduced “Twitter for Android” (Rechis, “Twitter for Android: Robots like to share too”). See also Paßmann and Gerlitz, “’Good’ Platform-Political Reasons for ‘Bad’ Platform-Data.” ↩

- Latour, “The Powers of Association”, Sahlins, Historical Metaphors and Mythical Realities. ↩

- Natale, “Unveiling the biographies of media.” ↩

- Sarno, “Citizen photo of Hudson River plane crash shows Web’s reporting power.” ↩

- Zdanowicz, “‘Miracle on the Hudson’ Twitpic changed his life.” ↩

- Frommer, “U.S. Airways Crash Rescue Picture: Citizen Journalism, Twitter At Work.” ↩

- f.e. Sarno, “Citizen photo of Hudson River plane crash shows Web’s reporting power.” ↩

- ibid. ↩

- Sysomos, “Inside Twitter”, Bunz, “Has Twitter reached its peak?”, Schroeder, “How Twitter Conquered the World in 2009.” ↩

- Kutcher, “Update from Ashton Kutcher about Twitter challenge,” 2:29–2:45. ↩

- ibid., 2:55–2:59. ↩

- ibid., 3:20–3:32. ↩

- Turner, From Counterculture to Cyberculture. ↩

- Weaver, “Iran’s ‘Twitter revolution’ was exaggerated, says editor.” ↩

- Morozov, “Iran Elections: A Twitter Revolution?” ↩

- Grossman, “Iran Protests: Twitter, the Medium of the Movement.” ↩

- ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Wikipedia, “Reblogging.” ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Turner, From Counterculture to Cyberculture. ↩

- Bruns, “Ad hoc innovation by users of social networks: the case of Twitter”, 5. ↩

- Löwgren, J. and Reimer, B. Collaborative Media, 19. ↩

- Bruns, “Ad hoc innovation by users of social networks: the case of Twitter,” 9. ↩

- Ibid., 10 ↩

- Halavais, “Structure of Twitter: Social and Technical,” 30. ↩

- Barone, “Why Twitterʼs New Retweet Feature Sucks.” ↩

- Schütz, “The Stranger” ↩

- Garfinkel, Studies in Ethnomethodology. ↩

- Schüttpelz, “From Documentary Meaning to Documentary Method” ↩

- NN, “Who first used the term ‘RT’ on Twitter?”. ↩

- ‘RT@BreakingNewsOn: ‘LV Fire Department: No major injuries and the fire on the Monte Carlo west wing contained; east wing nearly contained.’’ ↩

- ‘ReTweet: jmalthus @spin Yes! Web2.0 is about social media, and guess what people like to be social about? Themselves. Social Narcissism’. ↩

- ‘need to retwitter this itʼs so cool: brianoberkirch – At obvious hq a robot bird says potweet each time you twitter.’ For a more detailed account of the early forms of retweeting see Paßmann, Die soziale Logik des Likes, 263–291. ↩

- Schumpeter, Business Cycles, 84. ↩

- Sahlins, “Culture and Environment”, Sahlins, Historical Metaphors and Mythical Realities. ↩

- Latour, “The Powers of Association.” ↩

- Paßmann, Die soziale Logik des Likes, 273–280. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Collins, “The Sociology of Scientific Knowledge”, Bijker, Hughes and Pinch, The Social Construction of Technological Systems. ↩

- ibid. ↩

- Sysomos, “Inside Twitter”, Bunz, “Has Twitter reached its peak?”, Schroeder, “How Twitter Conquered the World in 2009.” ↩

- @ELIAS_01, July 8., 2009. ↩

- Phillips, This is why we canʼt have nice things. ↩

- Chadwick, The Hybrid Media System. ↩

- Paßmann, Die soziale Logik des Likes, 292–295. ↩

- N.N. “The Most Popular Twitter Apps According to the Blogosphere.” ↩

- Paßmann, Die soziale Logik des Likes, 296–303. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- TweetDeck. “Is it ok to change ‘Retweet’ to ‘RT’.” ↩

- Latour, Reassembling the Social.. ↩

- Sahlins, Historical Metaphors and Mythical Realities. ↩

- Latour, “Drawing Things Together”, 35 ↩

- Butcher, “Is Favorit a Digg killer?” ↩

- We can also observe how the literary genre of the business plan shapes technologies here: in most cases, they have to use the formula ‘like X, but for Y’. Technologies fitting into that formula are preferred, or perhaps even produced to fit into that formula. ↩

- Butcher, “Tweetmeme takes another bite at ranking Twitter links.” ↩

- Butcher, “Tweetmeme lets hoax ‘Zombie Swine Flu’ BBC story go-unchecked.” ↩

- ibid. ↩

- Tweetmeme, “Major Revamp Part 2.” ↩

- Schonfeld, “Tweetmeme is Getting Freakin’ Awesome” ↩

- The Wikipedia article on reblogging (ibid.) claims that the Twitter button’s green was taken from tumblr’s green reblog button. Whether this ‘came’ from tumblr to Twitter, from tumblr through Tweetmeme to Twitter or whether it was rather an in ‘invention’ of Tweetmeme as they had to visibly distinguish themselves from Digg’s orange, is speculation. ↩

- Nelson and Winter, An evolutionary theory of economic change. ↩

- Tripathi Chopra, “Meet the man who invented the re-tweet button.” ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Schonfeld, “Tweetmeme Wants To Be The King Of Retweets.” ↩

- For the notion of Twitter’s units (esp. retweets, likes and followers) as vague social media, similar to older social media such as gifts and money, see Paßmann, Die soziale Logik des Likes. ↩

- Stone, “Project Retweet: Phase One.” ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Perez, “Retweet.com Is No Competition for Tweetmeme.” ↩

- Halavais, “Structure of Twitter: Social and Technical”, 36. ↩

- Phillips, This is why we canʼt have nice things, Chadwick, The Hybrid Media System ↩